LATEST: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States”

14/04/2017

ARTICLE: Violations of Human Rights in Border Region between Guatemala and Mexico

14/04/2017On January 1, 2017, from the Caracol of Oventik, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) publicly confirmed its decision to “to name an Indigenous Governing Council with men and women representatives from each one of the peoples, tribes, and nations that make up the CNI. (…) This council intends to govern this country. (…) This council will be presided over by an indigenous woman of the CNI, (…) which is to say, a woman of indigenous blood who knows her culture. This indigenous woman spokesperson from the CNI will be an independent candidate for the presidency of Mexico in the 2018 elections.”

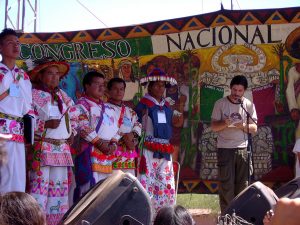

Meeting of the Indigenous Peoples of America, in the community of Vicam, Sonora, October 2007 © SIPAZ

This proposal, which has generated much stir and controversy, emerged last October at the end of the Fifth Assembly of the CNI in Chiapas through a joint statement with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) entitled “May the Earth Tremble at its Core” (paraphrasing the national anthem). By January, a total of 525 communities of 43 indigenous peoples had been consulted in 25 Mexican states. 430, that is, 82% of them, approved the proposal. The consultation process continues to date and the constituent assembly of the Indigenous Governing Council for Mexico is scheduled for May, once again in Chiapas. On this date, the name of the candidate will be announced.

Although the idea came from the EZLN at first and it was the command that proposed it to the CNI, it has clarified on more than one occasion that “it’s the CNI who will decide whether or not to participate with one of their own delegates, and in that case, it can count on the support of Zapatismo.” and “We told them that it didn’t matter if they won the presidency of the Republic or not, that what mattered was the challenge, the irreverence, the revolt, the total rupture with the image of the indigenous as object of pity and charity (…), that their audacity would shake the entire political system and that they would hear echoes of hope not from one but from many of the Mexicos below… and the belows of the world. ” The EZLN explains that, “[t]he goal isn’t that an indigenous woman of the CNI become president, but rather that a message of struggle and organization be taken to the poor of the countryside and the cities of Mexico and the world” (EZLN communiqué, “A Story to Try to Understand”, November 17, 2016).

To understand this new proposal, it is important to recall the CNI’s path over a little more than 20 years. In this period, the CNI has maintained itself as “the home of Indigenous peoples of Mexico”, sharing demands, meetings, and actions in defense of their land, territory, identity, and culture under the motto “Never again a Mexico without us” (Comandanta Ramona, Mexico City, October 1996). In this article, we will review part of its origins and trajectory to try to explain how and why it came to agree to this proposal, which is still in the making.

“Enough is enough” to more than 500 years of exploitation, looting, repression, and discrimination

Since the Spanish conquest, indigenous peoples have suffered exploitation, discrimination, and poverty. Books, reports, and statistics – past and present – would support this claim. Even the Mexican State has recognized the “historic debt” it has with its indigenous peoples. Professor Luis Villoro narrates how the Mexican Republic was constituted “by a Creole and mestizo power that imposed its conception of the modern state on indigenous communities.”

After the proclamation of Mexico’s independence in 1821, Mexico became a sovereign nation, but indigenous peoples continued to be exploited, not on the encomienda system [which was created to control and regulate American Indian labor and behavior during the colonization of the Americas], but on large estates. Furthermore, although the country was divided into many indigenous peoples with different cultures, the first constitutions inspired by the European model crossed with the idea of homogeneity of the nation which never reflected that plurality.

The Zapatista uprising of January 1st, 1994 was the expression of “Enough is enough” in a context of oppression and marginalization in which people and factors were changed but never the relationship of power in the background. The fundamental demands of the EZLN were “work, land, shelter, food, health, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice, and peace” and their achievement would have to be “new political relations between the rulers and the ruled” (First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, 1994).

Between 1994 and 1996, several negotiation processes were carried out between the EZLN and the Federal Government. At the same time, and to this date, it has generated several meetings and efforts to link Zapatismo with national and international civil society and, specifically, with other indigenous peoples. In January 1996, the EZLN convened the first National Indigenous Forum in which the foundations for what would give birth to the CNI were laid.

On February 16, 1996 in San Andres Sak’amchén de los Pobres, a Tsotsil municipality of the Chiapas Highlands, the EZLN and the Federal Government signed the agreements of the first roundtable on Indigenous Rights and Culture. Not only did they reflect the proposals of the EZLN, but also what was discussed among the more than 300 representatives of 35 Mexican indigenous peoples who arrived at the National Indigenous Forum the previous month. Backed up, not only by indigenous organizations but also civil and social ones, as well as intellectuals, the National Commissions for Intermediation (CONAI) and of Concord and Pacification (COCOPA, a legislative body that helped in the dialogues), the San Andres Agreements established what should be the historical, political, social, economic, and cultural principles to end racism, marginalization, and the exclusion of all indigenous peoples of Mexico, as well as to promote their self-determination.

“Living Democracy”

The CNI was formally constituted on October 12, 1996. In the first years of its existence, much of its agenda focused on what was discussed and initially approved in San Andres, as it seemed to be a solution to a wide range of the demands of indigenous peoples at a national level, as a whole and in their diversity. On the other hand, it is important to highlight the internal work that characterized this first stage.

From its first declaration, the CNI set out its central purpose: to make a “New Homeland”, “that homeland that could never truly be because it wanted to exist without us.” In its first resolution, the CNI decided to give its mandate to an Indigenous National Assembly to carry out the consensuses and agreements already reached. They clarified that, as indigenous peoples, they do not seek to “reproduce the forms of domination or control with which, for so many years, power groups in the country have oppressed us, but on the contrary, to establish new ways of living democracy” (First National Assembly, November, 1996). In this sense they have taken up the Zapatista principles “To serve and not to serve oneself; to build and not destroy; to obey and not command; to propose and not impose; to convince and not conquer; to go down and not upward (in the sense of denying power-over); to link and not isolate.”

A CNI Monitoring Commission was also set up to execute and monitor the agreements; develop diagnostics, analysis, and alternative solutions; elaborate proposals, work programs, facilitate liaison and communication among various working groups (San Andres Agreements Follow-up and Verification Commission, Indigenous Legislation, Land and Territory, Justice and Human Rights, Economic Self-Development and Social Welfare, Culture and Education, Communication, Women, Youth, and Indigenous immigrants).

With this structure, the CNI began to consolidate itself as a plural space of gathering, debate, and agreement to unite struggles and actions aimed at generating its autonomy and safeguarding its territories and cultures: “This is the space where we are the hope and project of a new humanity, because the struggle of our peoples is not against a particular government, but against a globalizing system that tries to eliminate us from the planet. This struggle with and for, the new humanity makes us brothers among the peoples” (Second National Indigenous Congress, 1998).

From the “Constitutional recognition of our collective rights” to the start of the “construction of autonomy through actions”

Shortly after signing the San Andres Agreements, the government of Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de Leon (1994-2000) presented a counterproposal to the one prepared by COCOPA, breaking with the procedure approved in advance between the parties. The dialogue was suspended. However, the San Andres Agreements became a reference text for Mexican indigenous peoples, who continued to mobilize and organize themselves to demand that the government ensure its immediate and comprehensive compliance, seeking a constitutional recognition of their collective rights.

To legitimize this option, the EZLN and the CNI called on the entire Mexican, indigenous, and non-indigenous population “to promote and carry out, together with other sectors of society, the National Consultation convened by the EZLN, for the Recognition of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the End of the War of Extermination in March,1999.” In the end, more than 2.5 million Mexican citizens participated in this consultation, expanding the basis for legitimacy for what is included in the San Andres Agreements.

In July 2000, after 71 years of uninterrupted rule, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost the presidency of the Republic to Vicente Fox of the National Action Party (PAN). From his inauguration, a change was observed compared to the previous administration: it put the issue of the armed conflict in Chiapas on the national agenda, ordered the withdrawal of 53 military checkpoints in the state, and presented the constitutional reform initiative of COCOPA on Indigenous Rights and Culture to Congress.

In February 2001, the Zapatistas held the “March of the Color of the Earth”, in coordination with the CNI, to defend the importance of this text before the Congress of the Union. They passed through twelve states of the Republic and, not without difficulty, Comandanta Esther spoke in the Chamber of Deputies at a moment of hope for the dialogue process and the rights of indigenous peoples. In the same place, Juan Chavez Alonso, a Purepecha leader from Michoacan and member of the CNI, said: “We are the Indians that we are, we are people, we are Indians. We want to remain the Indians we are; we want to remain the people we are; we want to continue to speak the language we speak; we want to continue thinking the word we think; we want to continue to dream the dreams we dream; we want to continue to love the love we give each other; we want to be what we are now; we want our place now; we want our history now, we want the truth now.”

Nevertheless, in April, President Fox enacted the “Indigenous Law” passed by the Congress of the Union, which did not even remotely represent the proposal of the COCOPA, which both the CNI and the EZLN rejected as a “betrayal” and a “mockery”. The CNI stated that the law “not only violates the will of the people and is unconstitutional, but is profoundly regressive in disregarding fundamental rights” (CNI Manifesto on Indigenous Law, May 2001). It denounced, for example, that the initiative “does not know the legal framework already established by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO) concerning the territories of our peoples and does not recognize our lands and territories according to the concepts included in that Convention. The term “territories” is rudely replaced by “places”, so that we are deprived of the immediate physical space for the exercise of our autonomy and for the material and spiritual reproduction of our existence.” It also stresses that the constitutional “counter-reform” granted to indigenous communities “in a charitable and pious way, the character of entities of public interest and not of public law as established by the COCOPA Initiative omitting to guarantee the practice of self-determination of indigenous peoples in each of the areas and levels in which they assert their autonomy.”

This law was to mark a break, not only with the government, but, with all the political parties (which through their vote led to its approval) for both the EZLN and the CNI. From that moment on, both declared that with or without legal recognition they would continue to promote the practice of their autonomy and rights: “We will not wait for the Mexican State to recognize our existence and our rights, we have won the recognition of civil society, we will walk our own path as we have always done” (CNI, Eighth National Assembly, November 2001). The CNI proclaimed the San Andres agreements as its own law and began to promote the direct practice of the autonomy of indigenous peoples: “We will put the San Andres Agreements into effect through the daily practice of indigenous autonomy, the construction of communal, municipal, and regional autonomies, and the integral reconstitution of our peoples.”

Building autonomy under constant siege

In the past as Indigenous peoples, and more clearly since its conformation, the CNI has not failed to denounce the constant and persistent abuses suffered by indigenous peoples: militarization, repression, systematic violations of their rights and constitutional guarantees, as well as the sustained effort of the government to divide them: “For centuries excluded, subdued, and dominated by those who have taken over the Homeland, and who, faced with the impossibility of exterminating us, have tried to destroy us by deceit, manipulation, and attempts at cooptation; they make an effort to divide us at all costs; they insist on making us believe that we are from the past; they insist on condemning us to oblivion, silence, fatigue, or the slow agony of cultural disintegration, and look forward to the moment of turning us into archaeological ruins or old museum pieces, or to cynically devour our decomposed remains” (Second National Indigenous Congress, October, 1998).

In Chiapas, the consolidation of Zapatista autonomy was made public in August 2003, by introducing a new organizational level of regional character with the formation of the Caracoles (snails in English) from which the Good Government Councils (JBG in their Spanish acronym, rotating structures composed of delegates of the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities) work. Representatives of the CNI welcomed the initiative and pledged to continue the example of the Zapatistas, promoting indigenous autonomy throughout the country, and defending the rights of indigenous peoples in practice.

Both in Chiapas and at national level, the construction of autonomy and the defense of territory in the face of threats such as megaproject impositions have gone hand in hand with repression in many places such as San Salvador Atenco, State of Mexico (where in 2006, clashes between police and the organized population against an international airport left two people dead, 207 people detained, five foreigners expelled, as well as the sexual harassment and rape of 26 women); San Juan Copala, Oaxaca; the Yaqui tribe (who seeks to prevent the construction of an aqueduct on their lands); Cheran (where they decided to govern themselves by the system of traditions and customs faced with the collusion of politicians with organized crime), and Santa Maria Ostula, Michoacan (organized against the roads and tourism megaprojects that are planned to be imposed in Nahua territory); Xochicuautla, State of Mexico (against the Toluca-Naucalpan road project), among others.

Meeting of the Indigenous Peoples of America, in the community of Vicam, Sonora, October 2007 © SIPAZ

In October 2007 in the Yaqui community of Vícam (Sonora), the Meeting of Indigenous Peoples of America was held, convened by the traditional authorities of the same tribe, the CNI and the EZLN. The meeting was attended by 570 indigenous delegates from 12 American countries, representing 66 indigenous peoples. In this context, it was reinforced that the problems related to Land and Territory were the ones that most affected the indigenous peoples not only in Mexico, but throughout Latin America. The final statement explicitly stated: “We reject the war of conquest and capitalist extermination imposed by transnational corporations and international financial organizations in complicity with the great powers and national states. We reject the destruction and plunder of Mother Earth through the occupation of our territories to carry out industrial, mining, agribusiness, tourism, wild urbanization, and infrastructure activities, as well as the privatization of water, land, forests, the seas and coasts, biological diversity, air, rain, traditional knowledge and everything that is born of Mother Earth. We oppose the certification of the lands, coasts, waters, seeds, plants, animals, and traditional knowledge of our peoples with the purpose of privatizing them.”

In 2009, in Santa María Ostula, municipality of Aquila, Michoacan, the 25th National Assembly of the CNI denounced that, “the government and pro-government repression unleashed against our peoples has been expressed in the murder and imprisonment of hundreds of indigenous leaders, as well as in the military and paramilitary occupation of our territories, criminalizing social struggle, and any organizational attempt that originates in our peoples in an independent and autonomous manner” (Statement on the Right to Indigenous Self-Defense).

On the other hand, in the last 10 years, analysis and actions of groups that are members of the CNI have made it clear that economic and actual powers (national and international companies and organized crime) have been playing an increasing role in looting, making possibilities of defense even more difficult.

Even in the midst of the storm, maintaining the capacity to take initiatives

Given this context of constant siege, in October 2016, the CNI, in a joint communiqué with the EZLN, considered that “the offensive against the peoples will not cease, but intend to make it grow until they have finished with the last trace of what we are as peoples of the land”, declared itself in a permanent assembly and announced that it will initiate a consultation with each of its peoples “to dismantle from below the power that imposes on us from above and that offers us a panorama of death, violence, plunder, and destruction.” The CNI specified very clearly that their struggle “is not for power” but to call on the indigenous peoples and civil society to organize “to stop this destruction … to build peace and justice by reweaving ourselves from below.” The same communiqué marked the continuity and deepening of what they have been denouncing and gave 27 illustrations of current dispossession of “the tempest and capitalist offensive that never ceases but becomes increasingly aggressive and has become a threat to civilization not only for indigenous peoples and campesinos, but for the peoples of the cities who must also create dignified and rebellious ways not to be murdered, dispossessed, contaminated, sickened, enslaved, kidnapped, or disappeared. ”

For the same reason, and in spite of it, the CNI and the EZLN proposed that, “the time to attack has come, to go on the offensive”; and concluded “it is the time of rebellious dignity, to build a new nation for all, to strengthen the power of the anti-capitalist left from below, for the guilty to pay for the pain of the peoples of this multicolored Mexico.”