LATEST: 2024 Elections, under fire?

22/03/2024

ARTICLE: 30th Anniversary of the Zapatista Uprising

22/03/2024When these people arrived and later, when the blockade was in place, there was silence in the community, neither cell phones nor modular phones were ringing, the only thing that could be heard, it even sounded sad, was the singing of the birds, the chickens, that normal noise of nature…

A cry of demand and a call to action

C ivil society organizations in Chiapas joined their voices to highlight and demand that the situation of violence that has been experienced since 2021 in the border and mountain region of the state be recognized and addressed, which, in the report “Siege on Everyday Life, Terror for the Control of Territory and Serious Violations of Human Rights” they classify as a non-international armed conflict and urge the authorities to deal with it as such.

This report briefly reviews the beginnings of the conflict and how it has been increasing, recounts the control strategies exercised by the groups in dispute, collects testimonies from inhabitants of the area and the human rights violations that they experience every day, it points out the control and collusion of state authorities and institutions with organized crime and finally makes some recommendations to the state regarding the recognition of the seriousness of the situation and some strategies for caring for the vulnerable population.

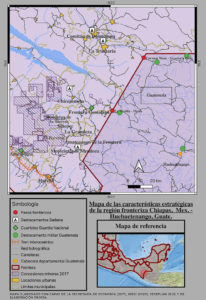

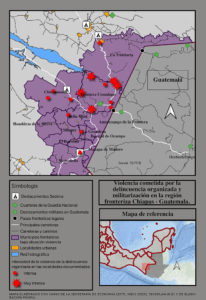

“The border of Chiapas with Guatemala is marked by an unrecognized armed conflict based on the territorial dispute of organized crime structures for the control of goods, services, people, legal and illegal products, as well as the life itself of the local population (…)”. The municipalities of La Trinitaria, Frontera Comalapa, Chicomuselo, Siltepec, Honduras de la Sierra, Motozintla, Mazapa de Madero, El Porvenir, La Grandeza, Bejucal de Ocampo, Amatenango de la Frontera and Bellavista are so far the main ones affected by the dispute. “Serious violations of human rights and international law affect both the local population and defenders of human rights and territory, for whom the risks of exercising freedom of expression and their defense actions are very high.” The report also points out that the conflict zone has become a silenced zone in which no one can talk and no one talks about it anyway. Hence also the relevance of the report and why we will dedicate this Focus section to it.

Escalation, diversification and continuation of violence

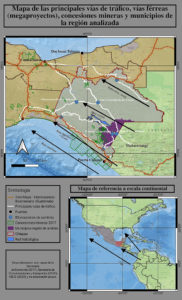

It is no secret to anyone that Chiapas is a territory rich in natural resources and that, furthermore, it is located in a strategic geographical area. It is the gateway for everything coming from South and Central America on its way north, mainly to the United States. This, as the report points out, makes it a fundamental point for the “control and promotion of both legal and illegal economies.” “The entire Chiapas territorial extension is structured by routes that are used for the transport of all types of merchandise, drugs, weapons and illegal livestock to the trafficking of people in international mobility. Since 1998, the jungle area on its border with Guatemala was considered by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a key corridor.”

All of the above explains the interest of the different organized crime groups in maintaining control of the area. “These groups operate at the territorial level through complex criminal structures made up of cartel members, local operators and state authorities at different levels, establishing criminal governance that goes beyond illicit businesses.”

As noted previously, this context of violence has worsened since the second half of 2021 when Gilberto Rivera, alias “El Junior”, who was the son of one of the operators of an organized crime group that until that time maintained control in the state, was murdered. This murder was claimed by an antagonistic criminal group and since then, from Frontera Comalapa, passing through Teopisca, Tuxtla Gutierrez, Pantelho and up to San Cristóbal de Las Casas, confrontations, executions and turf wars have multiplied, with the border area being the most affected. By 2022, there was a very significant increase in disappearances and displacements in the area. Furthermore, the deployment of surveillance drones and road blockades by armed men or by the same population that is coerced by organized crime groups have become part of everyday life.

“We find ourselves in a state of siege as we have reported on other occasions, the town is under siege by organized crime, we cannot move freely, leaving home means leaving with fear of what may happen to us when passing through their checkpoints, searches, harassment and intimidation in all its forms.”

The year 2023 was no different, as mentioned in the report, it had “two significant peaks in violence” in the Border-Sierra region. One was the so-called “Four Day War” that took place in the Nueva Independencia or Lajerio community in the month of May, where organized crime groups clashed relentlessly, also impacting neighboring communities and causing the forced displacement of at least 3,500 people. In September, there were different events in the municipalities of Motozintla, Frontera Comalapa, La Grandeza and Siltepec, where clashes, burning of trailers, deployment of armored vehicles adapted for combat commanded by heavily armed groups that settled in the region were reported on a par with the Armed Forces and National Guard.

Although some critical moments of violence stand out, it is important to note that this is a constant, the reality is that the population of the Border-Sierra region has not had a break since the dispute began. “(…) the violation of the right to life has become daily in the midst of an official position that minimizes or denies violence and remains indifferent to the worsening of the situation.”

Living under fire, fear and anxiety

The lives of people in the Border-Sierra region have been disrupted by the violence and control exercised by organized crime groups. Their reality has been transformed rapidly and the consequences are felt. Living day to day in anxiety, in fear, wondering if it is time to leave everything behind, where to go or is it possible to hold on a little longer and wait for something to happen that will return peace to their territories, this is how they live. now in that region.

“There are about 20 families who could no longer leave (to seek shelter) (…) I have a niece who endured hunger alone for six days, after six days I went to take her out of her house and she was in great panic. She came out jumping, looking around her and asked me if the men weren’t there, I told her no. In the middle of this there also comes a myth that they were recruiting men and more young people. They went to sleep in the mountains, pastures, mountains, caves. A lot of people ran away because of that.” This is one of the many testimonies that the report includes and that shows how difficult life is in the disputed areas.

In addition to living in fear and with the uncertainty of not knowing what’s next, mistrust has also settled into the population’s feelings. It is difficult to know who you can talk to without later being a victim of retaliation. As noted in the report, “this state of mistrust results in the fragmentation of community ties by distrusting one’s own neighbors, even one’s own family, which also causes important psycho-social impacts, mainly stress and paranoia.”

Another form of control exercised by organized crime groups has been to seize arable lands and prevent them from being worked, which has caused many families to be left without a livelihood, since their crops have been lost. There is no way to produce even for their own consumption. In addition to this, in the blockades set up and guarded by armed men, they carry out inspections and prohibit the passage of any type of merchandise, this translates into a shortage of food and basic products.

“(…) I was watering my cornfield when I saw these people about two hundred meters away pointing a gun at me. I wanted to talk to them, but one raised his hand stopping me while still pointing at me. ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ ‘I came to water my corn’, I said. ‘Don’t come here anymore, if you see us here, don’t come, come when we’re not here, go home!’ I spent the day at home, folding my hands because I couldn’t go to work anymore (…) I would go and if I saw them I would return home, if not, I would stay for a while, but I would hear the truck, turn everything off and go back home. I didn’t know what to do.”

“In the municipalities of Motozintla, El Porvenir, La Grandeza, Siltepec, Mazapa de Madero, Bellavista, Amatenango de la Frontera, Bejucal de Ocampo and Honduras de la Sierra, thousands of farmers have abandoned their crops due to violence.”

In this way, organized crime groups have been taking control of the territory and the population, sometimes with the use of violence that sometimes goes beyond words and, at other times, with actions that try to soften and normalize their presence in the region. In some communities, groups have come to present themselves as the “good guy” who has come to free them from the “bad guy.” This is how they have inserted themselves into daily life, co-opting violently or not (“it should be noted that the patience of the groups in the face of community resistance is very little and if co-option is not achieved, the consequences are very serious: physical attacks , disappearances, exemplary murders, dispossession, among others…”) to social organizations, young people and diverse populations.

“This narrative manipulation of the conflict increases the degree of tolerance towards violence, until it is normalized.”

Another mechanism used by criminal groups in this war for territorial control is that, to prevent the advance of the antagonistic group, they dig ditches that keep towns and communities isolated, fenced, which represents a further impact on going about one’s life, as it prevents free mobility and with this a countless number of daily activities are truncated.

“Classes at the basic and high school levels were suspended and health centers closed due to the risk that moving around the region entails for staff.”

But the control exercised by these players doesn’t stop there, another form that has been documented over the last few months is the economic aspect. In the report, it is mentioned that “in the border conflict, a set of economic strategies are deployed that organized crime develops both to strengthen control over the territory and to remedy the operational expenses involved in the dispute. This economy of conflict includes extortion, protection money, and kidnappings, but also the control of prices of agricultural products, income and other transactions of the local population. In addition to the confiscation of properties ranging from houses to crops and livestock.”

“A vendor from the community stood up one day and publicly complained that the sale of corn was free and that they had the right to sell to whoever they wanted… the next day they handed over his body… it was a huge trauma…”

It is known that groups make use of “borrowed names”, which has great legal implications as well as risks of being considered by the antagonistic group as part of the “enemy”, which can result in persecution, disappearance and murder, punishments that also occur in case of refusing to do so.

To all of the above, we add the exploitation and control of natural assets and resources such as water and mines found in said territory. The sexual exploitation of women and girls is also a constant, it is known that both women in international mobility situations and women belonging to local communities are victims of temporary forced disappearances and sexually exploited in canteens, brothels and houses occupied by criminal groups.

“The psycho-emotional consequences generated by living in the midst of this context are notorious: fear and despair reign, collective hysteria suddenly arises due to rumors, and mental health problems are aggravated by constant worry, helplessness and frustration.”

Burying its head in the sand

The situation in which thousands of people now live in the Border-Sierra region has been repeatedly denied by the Mexican government, mainly by the President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, and by the governor of Chiapas, Rutilio Escandon Cadena.

When Lopez Obrador has been questioned about the violence in Chiapas, he generally responds that it is not the case, that in Chiapas all is calm. In recent statements he has mentioned that, yes, there is displacement, but the number of displaced people (which currently exceeds 10,000 people) is not significant and that they would soon return to their homes. Taking into account what is documented and the testimonies collected in the report, it is evident that there are no conditions for this to happen. Even in his most recent statements after the public presentation of the report, AMLO maintained that his government has met its promises in the Southeast, that Chiapas is well below the national average in intentional homicides and even that non-governmental and civil society organizations present in Chiapas were stuck with the idea of confrontation from the time of the Zapatista uprising and that clarifying lies takes a long time, that surely everything was due to a media campaign against MORENA now that the electoral campaigns are about to begin.

This refusal only aggravates the situation, since there is no will to implement actions that put a stop to violence and control by organized crime.

“One of the State’s responses to the armed conflict has been the deployment of elements of the armed forces throughout the entire border territory (…) militarization has been a frequent strategy in Chiapas directly linked to crimes against humanity, to the creation of paramilitary groups and the accelerated deterioration of security,” the report states. Added to this is corruption at all levels of government and armed forces, which culminates in links with criminal groups and the creation of silenced zones, it also states.

“(…) organized crime interacts with government officials forming criminal structures that intervene and aggravate tensions and conflict over territorial control. Such is the degree of insertion into government structures that in some municipal seats it has been reported that the entire city council is within criminal structures and that they are at their service.”

The widespread situation of violence brings with it a serious deterioration of society, the systematic violation of human rights, “basic rights such as peace, life, dignity and personal integrity are put at risk and violated.”

Solidarity and union in the face of silence and emergency

In different municipalities of Chiapas, including those hardest hit by this wave of violence, thousands of people have gathered in numerous pilgrimages and marches to demand peace.

Likewise, both the Diocese of San Cristobal and civil society organizations have spoken out to highlight that “the civilian population was taken hostage, used as a shield, forced to participate in mobilizations, blockades and confrontations in favor of one of the sides in conflict. Basic supplies such as food, gasoline, gas, electricity and telephone company services were cut off, keeping the population in suspense and anxiety, incommunicado, with food shortages and even with the impossibility of moving for fear of reprisals.”

Also, after the latest clashes that have caused the forced displacement of thousands of people, both the population, churches and civil society organizations have organized to collect and deliver food, clothing and basic necessities.

The latest effort made to highlight the violence and the effects that it entails on the population is the report cited throughout this article, which culminates with a series of recommendations to the Mexican state and the international community, which are focused on the recognition and visibility of the conflict, the protection of the civilian population, guaranteeing the population access to their rights and investigation and access to justice for the victims.