ARTICLE: Sowing positions for self-determination – the peoples of Chiapas in their struggle for autonomy, the experiences of Chilon and Sitala

22/09/2018

LATEST: Mexico – Overwhelming Victory of “Together We Will Make History” Coalition in the Elections of July 1st

22/09/2018Violence, by creating many more social problems than it solves, never brings permanent peace.

The year 2017 ended in Mexico with dramatic figures in terms of forced displacement due to violence. Never before, since the armed conflict of 1994, have such worrying figures been reached in states like Chiapas.

They remain engraved on our retinas, the images of people – mostly women, boys, girls, and older adults – huddling under improvised plastic tents, that “helped” them to shelter from temperatures below zero degrees, typical of the winters in the Highlands of Chiapas, subhuman conditions that claimed the lives of several people.

According to the guiding principles on forced displacement of the United Nations, internally displaced persons are “persons or groups of persons who have been forced to flee their home or place of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or to avoid the effects of an armed conflict, of situations of generalized violence, of human rights violations or of natural catastrophes or those caused by human beings, and that have not crossed an internationally recognized state border.”

In regards to forced internal displacement (FID) in Mexico, very little information is available (in addition to the fact that not all victims make formal complaints). In 2016, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH in its Spanish acronym) published a special report on FID. It had requested information from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI in its Spanish acronym), which replied: “The General Directorate of Statistics on Government, Public Security and Justice does not have statistical information to determine a diagnosis of forced internal displacement.” When presenting the special report, the CNDH explained that in spite of the sampling work that emerged from questionnaires and visits that were carried out in the 32 states of the Republic, the results obtained did not allow a valid general projection on the dimension of the phenomenon, although they did show the need and urgency to address this problem.

One of the sources of information from civil society has been the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH in its Spanish acronym). CMDPDH questions its own calculations, considering them “extremely conservative” as they only include cases in which entire communities have had to move.

According to data from its last report, from January to December 2017 there were 25 episodes of mass forced internal displacement in Mexico, affecting 20,390 people. The displacements were registered in at least nine states, 27 municipalities and 79 localities. The states with the most episodes of forced internal mass displacement were Guerrero with seven, Sinaloa with five, and Chihuahua, Chiapas, and Oaxaca, with three each.

The state with the most displaced persons was Chiapas, with 6,090 people. In second place was Guerrero with 5,948, and in third place was Sinaloa with 2,967 victims. The biggest factor that generated FID was violence generated by organized armed groups, the cause of 68% of the total number of cases.

Similar to many situations of violence in Mexico, they found that in most of the episodes the victims most affected by the displacements were girls, boys, and women (in most of the indigenous cases). Other victims were older adults, campesinos, small business owners, businessmen, activists, journalists, human rights defenders and public officials. It should also be recognized that when it comes to an internal displacement for a prolonged or permanent time, not only are there consequences for the direct victims, but also indirect consequences for the broader population and the social fabric of the affected areas. It also mentioned Caritas San Cristobal de Las Casas A.C. in a pronouncement on current cases in the Chiapas Highlands region: “the conditions of the displaced persons, their needs and their economic limitations mean that even those who were not displaced have been affected.”

For its part, the International Commission on Human Rights (ICHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) have established that the forced displacement of indigenous peoples may place them in a special situation of vulnerability due to the intrinsic relationship they have with their lands. Furthermore, because of the destructive effects that forced displacement has on the ethnic and cultural fabric of indigenous communities, it generates a clear risk of cultural and physical extinction of indigenous peoples.

Chiapas: the state with the largest number of displaced persons

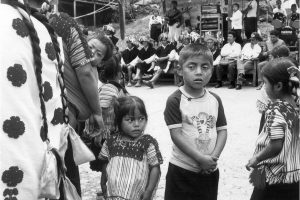

Sit-in of displaced people from Colonia Puebla, municipality of Chenalhó in front of the government building of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, April 2018 © SIPAZ

In Chiapas, the problem of forced displacement is nothing new, nor is it mainly linked to organized crime. Internal displacement due to political and religious issues in the municipality of Chamula (1960-1980), the hydroelectric project in Chicoasen (1980), and natural catastrophes such as the eruption of the Chichonal volcano (1982) or hurricane Stan (2005) in the coastal zone have not been forgotten. Displacements since the 1990s linked to issues of socio-political violence have also had a strong impact, especially on the indigenous population in the Highlands region and the northern part of the state, where massive displacements occurred in the years that followed the Zapatista Army of National Liberation’s (EZLN in its Spanish acronym) uprising, due to the strategies of the federal government to combat the revolutionaries and the emergence of armed and paramilitary groups that unleashed a heavy wave of violence.

As Martin Luther King said, “Violence, by creating many more social problems than it solves, never brings permanent peace.” This is clearly reflected in the old agrarian conflicts that began in the seventies between different municipalities over communal goods in the Highlands region that generated clashes and displacements, that have affected thousands of people in 2017 and 2018. According to the CMDPDH, the territorial conflict between Chenalho and Chalchihuitan, is the episode that registered the highest number of victims at a national level- 5,323 Tzotzil indigenous people were displaced in 2017. More than 900 hectares located on the boundaries between the two municipalities are in dispute due to the work of recognition and titling of communal property by the extinct Ministry of Agrarian Reform. To date, about 1,450 (¹) Tzotziles from Chalchihuitan remain displaced. They have organized themselves as the “Chalchihuites Autonomous Displaced Representatives Committee” to demand that their rights be respected.

In the municipality of Aldama, another agrarian conflict left more than 700 people homeless in February 2018. This conflict, in which several people from both sides died, continues without a solution. It is worrisome that there is still no clarity about the future of these people and the possible return to their homes.

Other victims formed “The Coordinator of Displaced Persons of the State of Chiapas.” They are native to the municipalities of Chenalho, Ocosingo, Zinacantan and Huixtla (affected by Hurricane Stan and who have been displaced without a response from the government since 2005).

In addition to these cases, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba) expressed their concern to us in an interview about possible thefts and human rights violations related to the projects of the Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which are currently operating and about which the incoming government has said that it plans to continue. Frayba affirmed that it sees the incoming government’s decision to continue SEZs as being in contradiction to the same government’s declaration for the respect of the San Andres Accords on indigenous rights and culture signed between the EZLN and the federal government in 1996, that it would protect the lands and the territories of the original peoples. Types of megaprojects related to SEZs have been the cause of several depopulations and forced displacements in Chiapas and other states of the Republic.

Further north: from displacements by megaprojects to displacements due to territorial wars between drug cartels

The phenomenon of displacement by megaprojects, such as mining projects, can be seen in other, more northern states. The UN Special Rapporteur, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, endorsed this in her report after her visit to Mexico in November 2017, mentioning the example of Guerrero. She also noted that the presence of organized crime occurs in areas where mining interests also exist, which increases the vulnerability of indigenous communities.

Here we touch on a key point of Guerrero and other more northern states, that organized crime has become a very strong player in the state: “at the beginning, the struggle between the different criminal groups was for the “square”, that is, the consumer market, but as it grows it becomes a whole company that monopolizes all criminal activities: kidnapping, extortion, land collection, protection rackets, theft in general. They also try to control the supply of labor for the production, sale, transfer, and export of drugs.”(²)

Its total control of the territory is used for production and transfer of drugs. Due to the divisions of the big cartels, due to the war against the narcos since the government of Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), there have been bloody fights between rival groups “with the purpose of generating terror both in the population and in their enemies. If this were not enough, they are at the service of the political group that dominates in the region to maintain power and seek to implement extractive projects. They also serve as a paramilitary group that inhibits social organization and struggle.”(²)

The Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center pointed out that the authorities are promoting their megaprojects without addressing the serious problem of violence perpetrated by organized crime groups in the same places. (3) On the contrary, collusion among state, business and criminal players has been shown.

In states such as Guerrero, where a high level of violence is experienced, journalism and being a defender of human rights are high-risk jobs. The rate of displacement of these sectors is high and affects the right to freedom of expression by creating “silenced zones,” the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) said this year.

A legal framework that does not fulfill its purpose

At the international level, there are several laws and treaties ratified by Mexico. Despite the fact that there is no Federal Law on forced displacement in Mexico, the Comprehensive Victim Assistance Program 2014-2018, a Protocol for the Care and Protection of Victims of Forced Internal Displacement (FID) in Mexico (2017), was prepared, and in the case of Chiapas, has been a state law since 2012: “The Law and the State Program for the Prevention and Attention of Internal Displacement”. (Guerrero instated a similar law in 2014)

In the case of Chiapas, the Law “has the purpose of creating the conceptual framework and guarantee of the rights of people who for various reasons are forced to leave their usual place of residence, defining what is considered an internally displaced person; establishing the rights of internally displaced persons, mandating the creation of both the State Program for the Prevention and Attention to Internal Displacement, and inter-institutional coordination through the establishment of the State Council for Integral Attention to Internal Displacement.”

This law states that the government has the obligation to install the State Council of Integral Attention, in a framework of sixty calendar days from entry into force of law; and that once the Board is installed, will have a term of ninety calendar days to issue the regulations of said law.

Despite these deadlines, these two obligations have not been met nor is there any official evidence of this. It was not until March 20th of this year that the State Council had its first session. This occurred after the IACHR requested in February precautionary measures from the Mexican Government for the displaced people of Colonia Puebla in Chenalho and it did the same for the displaced people of Chalchihuitan in March. The council had its first meeting on the preparation of the law’s regulations, 148 days after the first session of the council in August.

Frayba stated in an interview that due to requests for precautionary measures, FID began to have a political weight and that is why the government gave attention to the humanitarian situation, but not to the root of the conflict that is still in force. The precautionary measures granted were dealt with in a “superficial” manner in order to appear to comply with the Law, although the first difficulties soon began to emerge. In the case of Chalchihuitan, the government has not recognized all the victims as internally displaced persons. Frayba and the victims also mentioned that displaced people are not receiving information about the process. In contrast, the Law, under Article 15, says that internally displaced persons have the right to be consulted and to participate in decisions that affect them, as well as to receive information that allows them to make free and informed decisions. Displaced people in some cases are receiving food, medical consultations (although there is not always medicine), and children are receiving classes There are no other advances in the merits of the case, especially in regards to the root of the violence that led to internal displacement. On the contrary, last January it was reported that government representatives demanded that the displaced people from Chalchihuitan return to their homes despite the fact that there were no satisfactory security conditions for said return, considering that at no time were the armed groups in the region disbanded and that shots continue to be heard according to the inhabitants. Impunity in these cases is serious and at any moment the situation of violence could explode again.

In Guerrero, on the other hand, “although there is Law 487 to prevent and deal with forced internal displacement, for families it is not worth the paper it is written on and the worst thing is that they are families that are on the verge of death itself, however, the authorities of Guerrero neither see nor hear them.” (4)

The return of displaced persons does not necessarily mean a fundamental solution

The CMDPDH reported that “due to the absence of official or non-governmental institutions and programs that address the phenomenon of forced internal displacement, there is no certainty as to the number of returns that occurred during the year and the security conditions in which they occurred. However, it was possible to identify that of the 29 episodes of forced internal displacement recorded in 2016, five episodes ended in return. These returns are usually gradual and the total population does not always return, however, due to insecure conditions and the fear of becoming victims of the violence that surrounds them.”

When we review the historical cases of FID, it can be observed that there are few or no returns in which the rights of the victims in particular in terms of justice, security and compensation were fully respected.

In years or sometimes decades of displacement, people relocate and disperse to different places, often because of economic need or because of security and/or physical or mental health issues. The pattern of dispersion makes follow-up programs difficult to organize, because effective return operations usually have a collective nature.

A return does not always guarantee that the suffering of the victims will end. The return of displaced people from Quetzacoatlan, municipality of Zitlala, Guerrero, in 2016 showed that human rights violations related to the follow-up of victims who have returned also occur. In this case, the victims were accompanied by representatives of the state government who refused to sign a document that reflected the needs in this new risk situation. The authorities left telling villagers “we’ll see you in a month,” but time passed and that never happened. (5)

Another pending issue for the next government to see to

The state public policies of prevention and comprehensive attention to internal displacement in Chiapas and Guerrero have been few and often limited to humanitarian aid. Little political will has been noted at the three levels of government to address and resolve the underlying problem. The few achievements have been due to organized victim processes and/or pressure from Mexican or multilateral organizations (the IACHR in particular).

At present, civil human rights organizations that work on the topic of internal displacement advocate for the following recommendations: the recognition of victims of FID, an official diagnosis of the phenomenon, and a General Law for Prevention and Attention.

FID is, in fact, one of the topics of the 17 “Listening” Forums to Plot the Path of Pacification of the Country and National Reconciliation” that is currently being organized by the elected government of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador which will take office on December 1st. This can be an opportunity to discuss the issue by framing it in a context of generalized violence.

Notes:

(1) Caritas announcement

(2) Guerrero: Mar de luchas, montaña de ilusiones

(3) Tlachinollan: BOLETÍN | Los pueblos indígenas de Guerrero en el informe de la relatora de la ONU

(4) Tlachinollan: Opinión | “Si no se van de su pueblo, los matamos”

(5) Guerrero: Mar de luchas, montaña de ilusiones