LATEST: Mexico – Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador becomes President with broad social support

13/03/2019

ARTICLE: Final Ruling of the “Peoples’ Community Trial against the State and Mining Companies in Oaxaca”, Testing a New Form of Struggle For the Defense of Territory

13/03/2019“States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation”

In November of 1989 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child (now ratified by all countries except the United States). The document, which rapidly became the most widely ratified human rights treaty in history, lays out the rights of children (defined as anyone under the age of 18) and the duties that states have to protect these rights. The stated reality that children have inalienable human rights contrasts with older ideas of children being passive beings who need only to be cared for.

About 40 million children live in Mexico, in a wide range of social and economic settings. Like everyone on the earth today, children in Mexico are faced with the ugly reality of violence in many forms. From economic exploitation to bullying, to domestic violence and machismo culture, children of all ages are forced to navigate environments where violence thrives. While this is true of every society, children in Mexico face unique challenges as they grow up with both machismo and narco culture, and their many manifestations.

Economic violence and exploitation of labor

“Poverty is the worst form of violence”

In Mexico, more than 1 in 2 children and adolescents find themselves in situations of poverty, 20 percent of whom are in situations of extreme poverty. 1 This represents a percentage of children living in poverty which is significantly higher than the general population.2

Poverty leads to children’s physical needs, such as sufficient food and adequate shelter, going unmet. Economic hardship also affects access to education. Economic deprivation is the number one reason why children and adolescents drop out of school, either because of an inability to pay school fees or to join the labor force in order to contribute to the economic survival of the family. Living in poor neighborhoods can also make attending school more difficult due to lack of transportation. For young children, transportation is one of the main barriers to attending school.3

Of the millions of children in Mexico who work, the vast majority is in informal economic sectors, which can be hard to measure. It is known, however, that although many children begin work to help support their families, prematurely joining the workforce diminishes the possibility of continuing with formal education, and can permanently hurt a child’s long-term career opportunities.3

Family Violence in the Home

Physical violence is often committed against children by members of their own family. 6 out of 10 children and adolescents between 1 and 14 years old have experienced some violent method of child discipline in their homes. Severe physical punishment such as a hard slap or hit is less common, experienced by every 1 in 15 children in Mexico.1 While corporal punishment may still be socially acceptable and appear harmless in moderation, a 2010 study by Elizabeth T. Gershoff found that, in addition to decreasing long-term child compliance, even mild corporal punishment is associated with more aggressive behavior later in life.4

Psychological aggression should also be named as a significant form of violence. About 50 percent of children in Mexico have suffered some sort of psychological aggression by a member of their family. Despite the prevalence of various types of violence against children that happens domestically, the majority of physical violence against children and adolescents happens outside of the home. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), 8 out of 10 aggressions against children take place in school or in public.1

Bullying and Violence in Schools

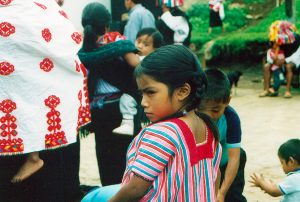

SIPAZ’s work with children at the Meeting on the Care of Mother Earth in Candelaria, Chiapas © SIPAZ

The educational system is perhaps one of the most important institutions for combating violence among and against children. The potential for schools to combat violence has not, however, stopped an alarming prevalence and severity of bullying. About 28 million children and adolescents are bullied in Mexico, making it the number one country in the world in cases of bullying. While bullying has existed for generations, social media and other forms of digital connection have increased its severity. Specific populations of children have a higher risk for being bullied. About 9 in 10 LGBTQ+ youth are bullied because of their sexual orientation, while more than 8 in 10 children living with disabilities experience bullying.5

Machismo Culture and Sexual Violence Against Girls and Young Women

Rivaling the pervasiveness of poverty among children in Mexico is the reality of sexual violence. Sexual violence is linked closely to machismo culture, an exaggerated male identity which includes the male domination and control of women and female sexuality.

Effects of machismo culture and male violence against girls include child pregnancies, child marriages, trafficking, forced prostitution, and other forms of sexual violence. According to the 2016 National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships (ENDIREH), 4.4 million women in Mexico have suffered sexual violence during childhood, including 1.2 million who were forced to have sex.6

Child pregnancies are perhaps the most obvious physical manifestations of sexual violence against girls. Among the 34 countries that make up the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Mexico ranks number one in teenage pregnancies.7 In 2016, there were 11,808 pregnancies of girls ages 10 to 14. In 70% of these cases, the father was 18 years old or older. In some cases, the violence continues when the girl is forced to marry the father.6 In Chiapas and Guerrero, over 30% of girls will get married or enter into a civil union before the age of 18, with the national average at around 25%.8 As with all crimes of sexual violence in Mexico, impunity lives large, with 94 percent of crimes unreported. Only 1 in 10 reported cases ever begins a judicial process.6

Another type of sexual violence against girls is trafficking and forced prostitution. About 21,000 children are trafficked for sexual exploitation each year, 45% of whom are indigenous girls.9 In another study of women working in prostitution, it was found that 83% of participants had begun sex work before the age of 16.10

Girls and young women are forced to navigate machismo culture on a daily basis- if not sexual assault, discrimination, harassment, and threat. The effects of this reality on health and development are hard to measure, statistics alone cannot capture the scope of sexual violence against children.

Narco-Culture and the War on Drugs

Between 2011 and 2016, (in Mexico) an average of 3 children were murdered every day.

The violence that has plagued Mexico in recent years has affected every part of society. A closer look reveals, however, that the war on drugs and organized crime have disproportionately affected adolescents. According to Save the Children, 8 percent of victims of homicides in Mexico are 15 to 19 years old. From 2004 to 2013, the homicide rate of children in Mexico rose from 1.9 per 100,000 to 3.1 per 100,000. In the same period, the rate of homicides of boys ages 15 to 17 rocketed from 9.9 to 26.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, which is classified by the World Health Organization as an “epidemic.” 70% of murders of boys ages 15 to 17 are with firearms.2 A report by the United Nations organization found that the homicide rate in Mexico of individuals under the age of 20 is the 24th highest in the world, fifth highest in absolute numbers.2

Another troubling reality is how criminal entities manipulate and force children into partaking of violence. Of criminal activity committed by adolescents, 62 percent occurred as part of organized crime or street gangs. A 2015 study by the National Electoral Institute (INE) looked at almost half of a million children between the ages of 14 and 17 years old. It was found that 4 percent of participants had been forced against their will to take part in a criminal organization.11 While this may not seem like a large number, taking into consideration the size of the study, it is easy to understand how criminal organizations are able to self-perpetuate through coercion of adolescents.

A way in which cartels and gangs are able to perpetuate their own existence is through soft power, or appealing to people through means other than force. One example of such appeal and romanticization of criminal activity is a genre of music known as narcocorridos, which overtly glorifies violence and other criminal activity. This music is growing in popularity in Mexico and the United States, and is bringing narco-culture to the mainstream. Television shows about drug cartels show the violence and danger associated with organized crime, but also the luxury lifestyle and power of cartel leaders. This a powerful message, especially to those living in poverty. In fact, for many people who choose to partake in organized criminal activities, the choice is usually an economic one.

Examples of Narcocorridos

“With goat horns

and a bazooka strapped to the back.

flying heads

passing through

we are bloodthirsty

proudly crazy

we love to kill.”

(The Centenary of the M1)

“If you’re poor, people humiliate you

If you’re rich, they treat you very well.

A friend got into the mafia.

because poor he no longer wanted to be.

Now he’s got plenty of money

they pay him a mountain per month.”

(Tucans of Tijuana)

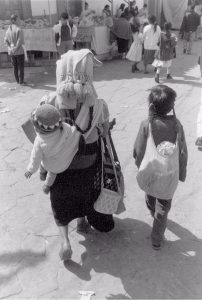

Violence Against Indigenous Children

Indigenous peoples make up 12.6 percent of Mexico’s population, and are concentrated in the southern states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero where SIPAZ works, as well Yucatán, Campeche, and Veracruz.12 71 percent of Mexico’s indigenous population live in poverty, well over the national average.13 Education is widely considered to be a proven path out of poverty, but for indigenous children and adolescents, this path is not clearcut. Just 27 percent of indigenous youth finish high school. Indigenous youth, especially girls, are at a higher risk for dropping out of school than their non-indigenous peers.12 Illiteracy among indigenous 15-year-olds stands at 25 percent, 4 times higher than the national average.14

Language is a large reason for the failure of Mexico’s educational system to provide indigenous children with an adequate education. Many indigenous children speak a language other than Spanish as their first language. An educational system which does not fully take this into account will predictably fail its students. Although educational reforms have led to bilingual education for many indigenous children, the new system is criticized as not valuing indigenous language, and for attempting to teach Spanish literacy to children who speak little to no Spanish.15 For indigenous youth in Mexico, the state’s failure to provide an adequate education brings added challenges to overcoming poverty.

Children in Situations of Migration

A population which is especially vulnerable to exploitation and violence is children affected by migration: children who stay in Mexico while their parents migrate for work, children who themselves migrate, and those living unauthorized in the United States, under threat of deportation and family separation. Children from Central America migrating to or through Mexico are also an at-risk population.

Looking at data from the Mexican government from 2017, over 18,000 children were apprehended by immigration authorities within Mexico, of whom 96 percent were from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. Furthermore, more than 7,400 of these children were unaccompanied.1 Migrant children are at a heightened risk for exploitation, including organ robbery and trafficking.16

In addition to these risks, children and adolescents in situations of displacement or migration face barriers regarding access to education. In Mexico, thousands of migrant children in Mexico, many of whom are unaccompanied, are not receiving formal education. As Director of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Audrey Azoulay states, “Learning is not a luxury. When migrants and refugees are denied education, everyone loses. Education is key to inclusion and cohesion and the best way to build stronger and more resilient communities”.17

In recent months, civil society organizations have denounced growing anti-migrant sentiment in Mexico, most notably on the northern border, where thousands of migrants from Central America are waiting to enter the United States while their asylum applications are processed. In Tijuana, violence against migrants has increased, and includes the murders of two teenagers from Honduras.18

Regardless of the risks, children migrate for various reasons including violence and lack of security, lack of economic opportunity, or a combination of these two push factors.

Addressing Violence Against Children: A Coordinated Response Between Government and International Organizations

In December of 2014, Mexico passed the General Law of the Rights of Children and Adolescents. Following this up, in August of 2017 Mexico’s government rolled out the National Action Plan to End and Respond to Violence Against Girls, Boys, and Adolescents. In part an implementation of the 2014 law, the national action plan was developed over six months, and included the participation of federal government agencies, two dozen civil society organizations, representation from academia, and consultation from children and adolescents. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) were present in the creation of the action plan.19

The National Action Plan to End and Respond to Violence Against Girls, Boys, and Adolescents addresses primarily corporal punishment, bullying, and physical and sexual violence against children and adolescents. The goals of the plan include the legal prohibition of corporal punishment, strengthening child abuse detection and protection mechanisms, and increasing violence prevention programs in schools.1

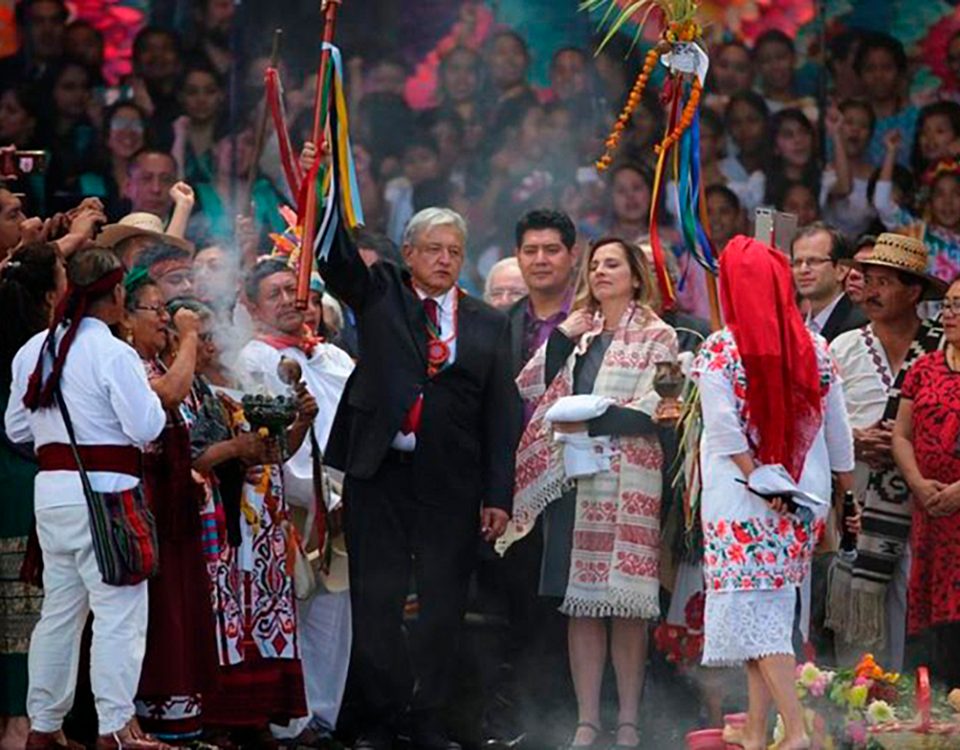

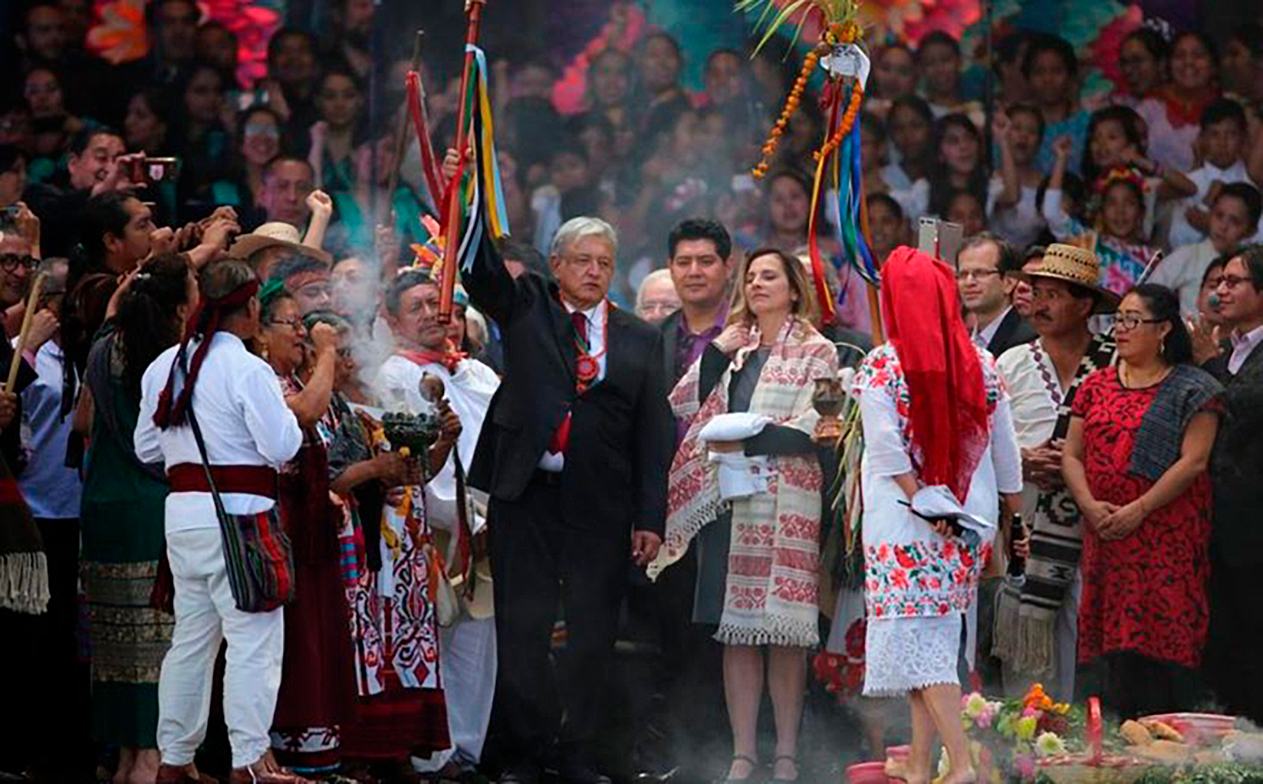

While the plan is relatively broad in its scope of interventions, many factors remain outside of the plan’s control, such as violence from organized crime and armed forces. Policies by the new federal government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador regarding security and responses to organized crime will also impact violence against children and youth.

Chiapas: Responses from Civil Society and State Government

Mexican civil society has addressed violence against children through a variety of interventions, many in health and education. In addition to direct interventions, non-governmental organizations have also put pressure on local, state, and federal government to address violence against children, among other problems. The Network for the Rights of Children in Mexico is a group of 73 civil organizations which, in addition to other interventions, since 2001 has been working together to advocate for the rights of children and affect federal legislation in regards to the legal protections of children. In Chiapas, the Network for the Rights of Children and Adolescents in Chiapas, made up of 8 organizations, shares a similar strategy of advocacy, but on a state and local level. The network also promotes the civil participation of children and adolescents, recognizing that the contribution of young people is vital for their own advancement.

Due in part to the advocacy of civil society, in 2015 the state government of Chiapas passed the Law on the Rights of Children and Adolescents of the State of Chiapas (LDNNACH) which enshrined in law a number of rights and protection measures for children living in Chiapas.21 Although it represents a symbolic step, civil society has critiqued the lack of political will to follow through with the legislation. According to the Network for the Rights of Children and Adolescents in Chiapas (REDIAS), protection measures that the law mandates are not in operation, and there remains a lack of adequate funding.22

This follows the government of Chiapas’s previous State Plan to Prevent and Eradicate Child Labor and Protect Permitted Adolescent Labor, which outlined steps the government would take to address child labor. Since then, however, there has been a lack of communication from the government about the results of the plan. Furthermore, a full budget for the plan has not been made public.23 While the previous state governments of Chiapas were willing to pass legislation that denounces violence against children, they did not have the political will to seriously address this violence. It remains to be seen if the new state government of governor Rutilio Cruz Escandón Cadenas will break this trend.

Looking Forward: Advocacy and Accountability

SIPAZ’s work with children at the Meeting on the Care of Mother Earth in Candelaria, Chiapas © SIPAZ

With the change of government, civil organizations have called on Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and his cabinet to make children and youth a priority. One of the projects proposed by AMLO is “Youth Building the Future,” which includes scholarships for 300,000 young people seeking to pursue university studies, and economic support for 2.3 million young people to access job training in workplaces for one year.

However, the absence of reference to children in the new president’s speeches is a cause for concern, and there is no known proposal that seeks to address the structural and cultural components of the violence that children in Mexico continue to face on a daily basis.

These proposals are urgently needed and should include mechanisms for the participation of children, adolescents, and young people, as well as organizations defending their rights, in order to bring about changes that will allow for a more comprehensive and effective protection of the human rights of children.

*** *** ***

-

Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF) Informe Anual | México 2017 (México, D.F., 2017)

- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CNDH) Adolescentes: Vulnerabilidad y Violencia (Ciudad de México, 2017)

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF) La niñez y la industria maquiladora en México (Ciudad de México, 2018)

- IPAS México, Comunicado de prensa Violencia Sexual y Embarazo Infantil en México (2018)

- México News Daily, In OECD México no. 1 for teen pregnancies (2017)

- The Guardian, Mexico’s lost generation of young girls robbed of innocence and education (2017)

- El Economista, México, sin cifras precisas sobre trata (Rubén Torres Y Jorge Monroy, 2017)

- Publimetro, México, segundo lugar a nivel mundial en turismo sexual infantil (2017)

- Elizabeth T. Gershoff, More Harm Than Good: A Summary of Scientific Research on the Intended and Unintended Effects of Corporal Punishment on Children (2010)

- Ollinac, LOS 5 DATOS MÁS PREOCUPANTES DE LA CONSULTA INFANTIL Y JUVENIL 2015 (2016)

- Univision, El Chapo Territory, 2013

- Bullying Sin Fronteras, Estadísticas Mundiales de Bullying 2017/2018. Primer Trabajo Oficial en el Mundo contra el Bullying (2018)

-

Arena Pública México, ‘foco rojo’ en tráfico de órganos, niños migrantes principal blanco: Unicef (2017)

- The Guardian, Mexico investigates after teens from migrant caravan killed near US border (December 19, 2018)

- Animal Político, Pide la UNESCO asegurar el acceso a la educación para los niños migrantes y desplazados internos (22 de noviembre de 2018)

- The Borgen Project, Five Important Facts About Indigenous Education in Mexico (2017)

- El Universal, Over 70% of Indigenous People in Mexico Live in Poverty (2018)

- The Guardian. ‘The help never lasts’: why has Mexico’s education revolution failed? (2017)

- Rainer Enrique Hame, Bilingual Education for Indigenous Peoples in Mexico (2016)

- Global Partnership to End Violence against Children Pathfinding Country Progress Report (2017)

- UNICEF Annual Report 2017 Mexico

- Poder Judicial del Estado de Chiapas, LEY DE LOS DERECHOS DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y ADOLESCENTES DEL ESTADO DE CHIAPAS (2015)

- Chiapas Paralelo, Por falta de voluntad política, Gobierno de Chiapas muestra abandono hacia la niñez (2018)

- Melel Xojobal, PRONUNCIAMIENTO POR LOS DERECHOS DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y ADOLESCENTES TRABAJADORES (2015)