LATEST: Pope Francis’ Visit to Mexico – A Word to the Wise is Enough

02/06/2016

ARTICLE: From the Relatives of the Disappeared to Human Rights Defenders

02/06/2016“Because the disappeared and murdered every day and at every hour and in all parts are truth and justice […} We should form a whirlwind in the world so that they give us back our disappeared alive.”

Ayotzinapa: the tip of the iceberg

Anniversary celebration of the missing student, Julio César López Patolzin, on his 25th birthday. His aunt and niece hug while a live band plays his favorite songs. Tixtla, Guerrero. Mexico. January 29, 2015 © Emily Pederson

The news about the forced disappearance of the 43 students from the Isidro Burgos Teacher Training School in Ayotzinapa that happened in Iguala, Gerrero, on the night of September 26 to 27, 2014, has gone around the world. The so-called “Iguala Case” placed the theme of forced disappearance in the country in the media spotlight and today it is known that Ayotzinapa is only the most visible face of this problem. “Mexico is a huge mass grave“, Javier Sicilia, member of the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity (MPJD in its Spanish acronym), declared in 2014, following the discovery of hidden graves across the Republic.

“Many families here in Mexico are dead even though they are living, cut open, frozen in mourning, because what we most loved in life was snatched from us: our loved ones“, the mother of a disappeared person in Michoacan wrote in a letter to Pope Francis on his recent visit. Like her, tens of thousands of testimonies tell how their relatives “left home one day and never came back, being in an uncertain world: they are not dead and they are not alive. Where are they? Others, in their homes, were savagely taken out to be disappeared or murdered.” The National Register for Data on Missing or Disappeared Persons holds that in Mexico to date there are over 27,000 people whose whereabouts are unknown.

In spite of this alarming figure, multiple organizations and media point out that the total number of people missing might be even higher. As Amnesty International (AI) indicated in the report “An Idle Deal” (“Un trato de indolencia”, 2014) “the majority of the crimes remain unreported, so the real magnitude of the problem is unknown and the official figure could be underestimating the seriousness of the issue.” For one thing, the government register only includes cases of disappearance that have a previous inquiry from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which according to the United Forces for Our Disappeared in Mexico (FUNDEM in its Spanish acronym) is only one in every nine. It excludes undocumented migrants who are disappeared – despite being one of the groups identified as being highly vulnerable regarding this problem – as well as bodies found in graves or who remain in hospitals and centers of the Forensic Medical Service. As the National Survey of Victimization and Perception (ENVIPE in its Spanish acronym) 2015 indicates, many families opt not to report due to mistrust in the authorities or because they see it as a waste of time, while victims’ relatives’ organizations point out that fear of reprisals by the authors of the disappearances is also frequent. Furthermore, the actual government recognized before the United Nations Organization (ONU) Committee Against Forced Disappearance that it does not have a clear number of disappeared persons. This lack of reports and of an exhaustive register of forced disappearances allows for the possibility that the real figure for disappeared persons in the country could be over 300,000 as members of FUNDEM have reported.

How is it possible?

Victims of organized crime. Third prize of the World Press Photo 2014. Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico. March 8, 2013 © Christopher Vanegas

The country has reached this worrisome situation through a complexity of factors. For one thing, organized crime groups have penetrated the social fabric in a major portion of the states of the Republic, and more intensely in the north of the country, particularly near the border with the United States. This is due to eagerness to control the drugs routes, mainly to the neighboring country. This spread has been a result of the inefficiency of the authorities in combating organized crime groups, also known as cartels, and even their collusion with them, as various human rights organizations and media have noted. These gangs, who profit from illegal activities such as drug, arms and organ trafficking; human trafficking or extortion and kidnapping, have involved part of the population in these businesses, both through payments as well as through threats to pressure their participation. The generalized situation of poverty that Mexico is living through has facilitated the spread of these criminal organizations.

Bodies of executed people exhibited in public, dismembered corpses, decapitated or hanged people are examples of the terror or exemplary punishment “messages” that the organized crime groups send. These messages exemplify the consequences that either not cooperating or reporting the abuses of the gangs can have. Threats are directed at rival gangs – in dispute over exclusive control of an operation in a given territory -or at the authorities and society in general, causing generalized fear and terror to get their cooperation and inhibit reporting. Forced disappearances are another face of these practices.

Since 2006, the year of the start of the so-called “War Against Drugs” by Felipe Calderon (National Action Party, PAN in its Spanish acronym), President of the Republic from 2006 to 2012, over 155,000 people have been murdered and some 300,000 have been forcibly displaced due to violence, according to data from the state and the Center for Vigilance of the Internally Displaced respectively. As an international commission of experts, coordinated by the British journal The Lancet and Johns Hopkins University noted, the “intolerable levels of violence, insecurity and corruption have caused massive displacements in Mexico and Central America, with similar levels to those documented in war zones.” In the opinion of Gilberto Lopez y Rivas, anthropologist and contributor to La Jornada, forced disappearance has a political character: to eliminate social struggle to facilitate the advance of neoliberalism and its enterprises. “Seeing the issue of disappearance or extra-judicial killings from a political viewpoint allows us to see what they want to achieve with these methods of force, which is to break the resistance of our peoples.”

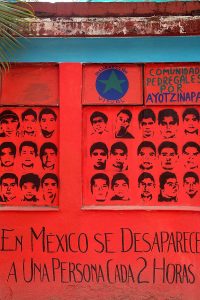

Mosaic in memory of the 43 missing students. Rural Normal School Raúl Isidro Burgos. Tixtla, Guerrero, Mexico © SIPAZ

Numerous observation and human rights defense organizations have spoken out regarding the situation. The Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR), which after its visit to Mexico “could confirm that the disappearance of people in large parts of Mexican territory has reached critical levels”, and the Office of the UNO Commission for Human Rights that claimed that Mexico presented a “critical situation regarding disappearance.” Statements of the relatives of the disappeared also stand out, like that of Nadin Reyes from the Relatives Until They Are Found Committee, (Comité de Familiares Hasta Encontrarlos), who asserted that forced disappearances in Mexico “form part of state policy, systematic and generalized”, a crime “against humanity” that affects relatives, victims and the population at large.

Nothing new

The period from 2006 to date has seen the most notable upturn of forced disappearances after the decade of the 70s, when there was a huge wave of disappeared persons during the so-called “Dirty War” – a time in which the state tried to silence the opposition voices that were calling for agrarian reform, health, education, democracy and social equality. On a national level, some 1,350 persons were disappeared, of which some 650 took place in the state of Guerrero, as indicated by the UNO Work Group report, 2012. According to the source, the purpose of the disappearances was to deactivate support for a number of armed dissident groups in the region.

One of the most emblematic cases is that of Rosendo Radilla Pacheco, a campesino and corridos singer songwriter, who was never seen again after being held at a military checkpoint at Atoyac de Alvarez, Guerrero, in August 1974. Rosendo, who had been mayor and had worked for the health and education of his people, was last seen in the old Atoyac military barracks. At present, his family continues to seek the truth, demanding his appearance and that justice be done.

Unlike the disappearances perpetrated during the Dirty War, most of which were committed against activists or dissident group sympathizers, today the disappearances extend to people without any social militancy or politics, many of them of working age, according to civil society organizations. It is suspected that some of the disappeared may have been kidnapped by organized crime groups and may be held doing forced labor for the cartels in activities related to the planting and processing of drugs. Likewise, in recent years there has been an increase in the disappearances of highly qualified professional people, most of them engineers experienced in the installation of antennae, as well as architects, doctors and veterinary doctors. According to the president of the Security Commission of the Senate of the Republic, “that trained people in these fields have been disappearing is neither by chance nor accidental.” The Army and the Marines have found sophisticated communication systems composed of over 400 antennae which they suspect were developed by specialists disappeared by organized crime.

Under the cloak of impunity

Although Mexico ratified the International Convention for the Protection of all People from Forced Disappearance in 2008, combating this problem continues to be ineffective. “In Mexico it does not matter if the disappearance is a case of a hidden situation or a high profile case, the authorities seem unable to give solid and institutional responses that are aimed at finding the truth and guaranteeing justice”, Amnesty International sentenced.

Many organizations and relatives of the disappeared have concluded that the search for those whose whereabouts are unknown is commonly deficient. “Our country does not have search mechanisms”, the mother of one young disappeared woman asserted. There are hundreds of testimonies about how the relevant authorities do not carry out the required basic investigative actions. They begin the inquiries late and do not even bother to investigate some cases. Furthermore, many families have reported being treated with disinterest, in a hurtful way, or insufficiently by the relevant legal authorities: “When I arrived to make the report they told us that she had gone off with her boyfriend. That’s what they tell us, that they go because they want to. We have great pain! When our children disappear, we don’t know what to do, where to turn to, where we have to go for them to help us to to find our children”, the mother of a disappeared girl stated. Sometimes they have been denied access to records and have even been asked for payments to carry out judicial procedures or to facilitate the investigations. Moreover, the CIDH has received reports of threats and harassments against families to drop the search for truth and justice. One mother pointed out, “they tell me, don’t search anymore because I’m going to cut off your tongue. Don’t search anymore because your other three children are going to appear at the door of your house and you’re going to have them on your conscience.” Many families have changed their address for fear of reprisals by the perpetrators of the disappearances.

There are many who have accused the State of carrying out a policy of simulation as regards the prosecution of justice in the cases of disappearance. According to AI, “in the majority of cases, the investigation does not appear to be directed at determining the truth of what happened. The authorities limit themselves to carrying out some actions of little use in the inquiry. This type of investigation is simply a formality that seems to be destined beforehand to be unsuccessful.” As if that were not enough, there are cases in which the investigations have focused on documenting the private life of the missing persons, criminalizing the victim, insinuating that they had ties with organized crime. In this scenario, it is not surprising that there have been only six sentences handed down at the federal level of the entire country for the crime of forced disappearance according to the Committee for Forced Disappearance of the UNO.

For more information (in Spanish):

- Amnistía Internacional: “Un trato de indolencia”. La respuesta del Estado frente a la desaparición de personas en México.

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas: La desaparición forzada en México: una mirada desde los organismos del Sistema de Naciones Unidas.