ANALYSIS: Human rights in Mexico – “regression,” “simulation,” and “impunity,” argue civil organizations

05/09/2014

ARTICLE: Tlachinollan, struggling alongside indigenous peoples of the Mountain region of Guerrero for twenty years

05/09/2014“I did not want to leave. If it had not been for the violence and lack of work, I would have stayed in my country. I do not do this for pleasure; it is just that there are no other options. Everyone is fleeing the country. And the problem is that everyone from above is corrupt—they only look after their own interests.”

A Honduran migrant, interviewed in Palenque in July 2014

On 19 July 2014, few migrants can be found in the Migrant Home of Palenque. “The train just passed yesterday,” said sister Nelly, member of the “jTatic Samuel Ruiz García House for the Path” of Pakal-na. Those who stay are resting or washing their clothes before leaving the shelter which for a few days has served as a refuge. We approach a group of migrants relaxing in the sun. “We are worried,” a Honduran migrant tells us. “We arrived the day before yesterday and we must leave today. But we do not know what to do. We fear for everything they have told us about what happens to migrants in Mexico.” Some say that they did not know that the situation was so dangerous, and for the majority of these migrants, this is the first time they leave their countries. “But we also cannot return to our country. There we can find no work and it is dangerous to live,” says another.

Central American migration through Mexico

© SIPAZ

The document concludes that the situation of Central American migrants in Mexico constitutes a humanitarian crisis: “The stark frequency of kidnappings, extortion, human trafficking, rape, and murder make the difficult situations faced by Central American migrants in Mexico at the top of the list of the worst humanitarian emergencies in the Western Hemisphere.” Each year, tens of thousands of migrants cross through Mexico illegally to make it “North” toward the United States, in search of the “American Dream.” In recent years, the number of migrants who come from Central American countries has grown considerably. It is difficult to find exact numbers, but according to the U.S. Border Patrol, the number of non-Mexican migrants who have been detained by U.S. authorities has tripled in the past couple of years (54,098 in 2011 and 153,055 in 2013). The great majority of migrants hail from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

The reasons these persons emigrate vary. Normally, generalized violence, lack of job opportunities, and extreme poverty in countries of origin are the most common motivations. According to the World Bank, 60% of the Honduran population, 53.7% of Guatemalans, and 34.5% of Salvadoreans live below the poverty line. Furthermore, in these countries, organized crime functions with near-total impunity, thus leading to a climate of violence and insecurity, above all in Honduras, a country that, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), has the highest murder rate of the world at 90.4 homicides per 100,000 persons. Death threats, extortion, kidnappings, human trafficking, and the fear of being forcibly recruited by the “maras” (criminal gangs) or organized crime are part of daily life in Central American countries. For many, migration has become the only alternative to being killed or being forced into becoming hitmen. “We just want to live honestly,” says a migrant in the Migrant’s Home of Palenque, “but now in Honduras that is impossible.”

In recent months, the issue of migrant children has garnered a great deal of media attention, nationally and internationally. The number of these migrant children has increased exponentially. According to the WOLA report, “more than 47,000 unaccompanied migrant children have arrived to the U.S. during this fiscal year, with nearly 35,000 coming from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.” Reflecting on this migratory flow, President Barack Obama recognized on 2 June that the situation on the U.S.-Mexico border is “an urgent humanitarian situation.” Many of these migrant children seek to be reunited with their relatives in the U.S. The U.S. government has declared that its immigration control policy has not changed, and that it will continue to deport “illegal aliens,” whether they be children or adults.

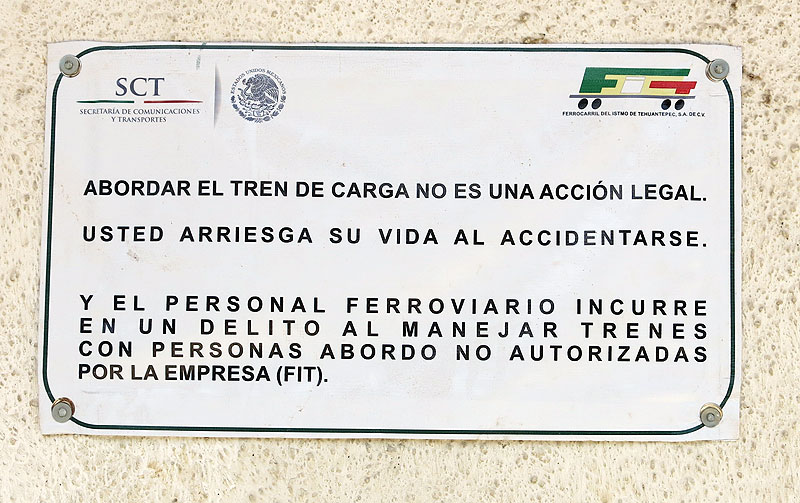

Though such U.S. policies can be expected to continue, it is quite likely that these migrants for various reasons will continue leaving their countries to undertake an uncertain trip without knowing with certainty when, how, and even if they will arrive at their destinations. To travel to the border between Mexico and Guatemala -the so-called “Southern Border”– is not so difficult. Indeed, the Guatemalan, Honduran, Salvadorean, and Nicaraguan governments have ratified the Single Central American Visa that allows for free movement of citizens of these countries. Once in Mexico, the path that is least controlled by migratory policy is the railways. Migrants get on to “La Bestia” (“The Beast”), a freight train that travels north from southern Mexico. From the border with Guatemala, there are two routes that can be taken: the “Caribbean route” beginning in northern Chiapas that passes through Tenosique (Tabasco) and Palenque (Chiapas), continuing along the Gulf of Mexico, and the “Pacific route” that begins in Arriaga, close to Tapachula in Chiapas, and continues on the Pacific coast, passing through Oaxaca state. Clutching onto the train for several days, migrants traverse the entire country confronting a number of risks—which is why the path is known as the “infernal route.” Exhaustion, hunger, extreme temperatures, and the possibility of falling off are just some of the dangers. However, the greatest fear is to become yet another victim of attacks by organized crime. According to the WOLA report, “The long trip atop the train is physically dangerous, and the lack of security leaves immigrants at the mercy of Central American gangs, bandits, kidnappers, and corrupt officials.” To travel on this route it is quite common to become a victim of robbery, kidnapping, and extortion, given that migrants represent an important source of income for organized crime. According to the “Halt Kidnapping” group, there were 1,766 kidnappings during the first half of 2014, an increase of 56% compared with the same period of 2013. Many migrants relate that the gangs sometimes will charge for the train travel and then, in the worst of cases, capture migrants to demand that they provide the telephone number of a relative in Central America or the U.S. The bandits will then demand that relatives pay a ransom if they do not wish to have the migrant in question be tortured or killed.

Throughout the journey, it is clearly women and children who represent the most vulnerable groups. For women, the risk of being victims of abuse and labor or sexual exploitation is quite high, such that many of them in fact inject themselves with contraceptives before beginning the journey so as not to run the risk of becoming pregnant. According to Amnesty International’s 2009 report “Invisible Victims: Migrants on the Move in Mexico,” “[a]ll these irregular migrants run the risk of suffering abuses, but women and children -especially the unaccompanied- are especially vulnerable. They run the grave risk of being subjected to trafficking and sexual assault at the hands of criminals, other migrants, and corrupt authorities. Though only a few cases are officially documented, with practically none entering the court system, some human rights organizations and experts on the subject estimate that up to six out of every ten females, adult and minor, suffer sexual violence during the trip.”

In this violent situation, gang members act in almost total impunity, and several cases of collusion with the authorities have been found. As Jorge Bustamante, UN Special Rapporteur on migrant rights, noted in June 2008, “transnational migration continues to be big business in Mexico, promoted principally by transnational networks of gangs that are involved in contraband, human trafficking, and drug trafficking, with the complicity of local, municipal, state, and federal authorities […]. As such, impunity for the violations of migrants’ human rights is a generalized phenomenon. Given the ubiquity of corruption at all levels of government and the extensive relationship several officials have with gang networks, extortion, rape, and attacks on migrants will continue.”

Beyond this, Mexico’s migratory policy stresses the arrest and deportation of migrants, leading to the possibility of further human rights violations. A study carried out by the No Borders group notes that “arrest is not an exception, as it should be, but rather the rule […]. Migration increasingly comes to resemble a crime and not a right, given that migrants continue to be detained at all times on the pretext of national security, until they demonstrate that they plan to stay in our country.” According to the report, Mexico’s National Institute on Migration (INM) registered 86,929 arrests (including 81,394 Central American migrants) in 2013. Furthermore, 14,073 of the arrested were women, and 9,893 minors.

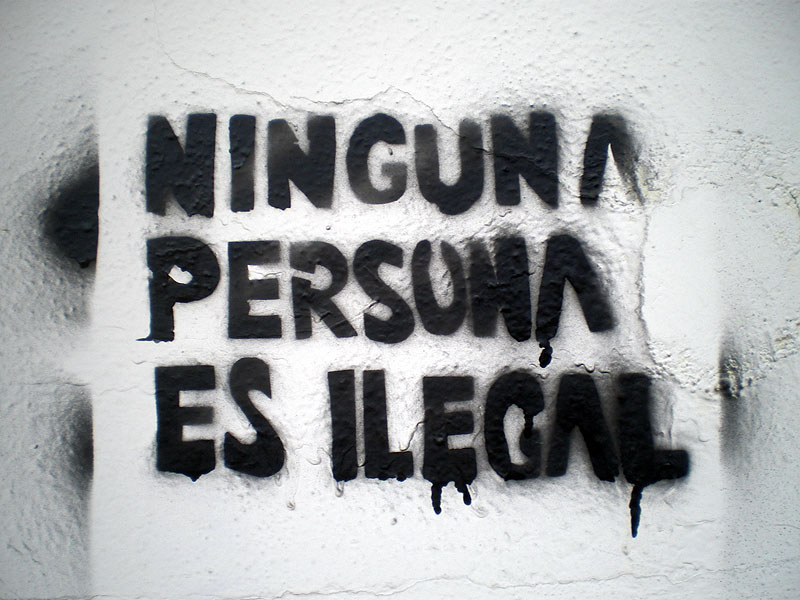

The criminalization of migrants

As in the U.S., the tendency in Mexico has been to criminalize migration. Migrants are not recognized as subjects of rights but rather are viewed as criminals who should be kept far from international borders. Neglect by governmental institutions thus makes them easy targets for criminal organizations. In the majority of cases, abuse and rape continue to go unpunished. The “Militarization, criminalization, and forced disappearance of migrants” preliminary hearing of the Peoples’ Permanent Tribunal (TPP) has declared that “these crimes are the result of the subordination of the Mexican authorities to the supposed imperatives of ‘national security’ and ‘free trade’ imposed by the U.S. These policies necessarily imply the militarization of borders, the criminalization of undocumented migrants and their protagonists, and the commodification of the migrants, who are converted into structurally essential factors yet treated as disposable in the short term.”

In light of this situation, the Mexican government continues to attempt to contain migratory flows by expanding the controls in place on the Southern Border between Chiapas and Guatemala. On 11 July, Secretary for Governance Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong indicated that “this is a decision by the Mexican State to not continue allowing Central American migrants—as well as Mexicans—to risk their lives atop these freight trains.” He added that “whoever does not have the required documents to enter our territory and that of the U.S. cannot be allowed to be in our country, and we cannot allow them in to take care of them […]. Whoever does not have a visa to enter our country will be returned.” In Huixtla, Chiapas, on 30 July, INM agents carried out one of the first operations to prevent migrants from boarding the train. Other similar situations were repeated the following month, and raids and arrests were carried out in bus and train stations in southern states.

What is happening in Mexico also happens in the U.S., where the government prefers to invest millions of dollars in border patrols, detention centers, and deportations to inhibit the entrance of irregular migrants. The burgeoning controls that have emerged on traditional migratory routes has led migrants to use other means which are less militarized but more dangerous, as seen in the Sonora Desert between Mexico and the U.S.

According to the TPP, the situation of poverty and violence that is experienced in Central American countries and the rise in migration to Mexico and the U.S. in recent years are the result of the imposition of neoliberal policies twenty years ago, when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. “NAFTA and its complements […] have deepened poverty, inequality, discrimination, and the plundering of resources and lands […] that necessarily lead to a generalized violation of civil, political, cultural, economic, social, and environmental rights. This includes the imposition of structural and material conditions that impede the truly free exercise of the right to migrate and not to migrate, and that produce forced migration and forcible displacement as consequences. These are all expressions that converge into a massive process of exodus or exile.” Since the start of NAFTA, it is calculated that approximately 6,000 persons have died on the border between the U.S. and Mexico.

Migration as a right

Many activists observe that migratory flows continue and will continue, even if governments continue to militarize the borders and migratory routes. They stress that what is needed is for migration to be recognized not as a security emergency but rather as a humanitarian emergency. The “Open letter on the humanitarian crisis of migrant minors,” published in July 2014, directed to the governments of the U.S., Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, and signed by several civil organizations, collectives, and social networks, affirms that “an additional key factor has been the decisive complicity of the governments of the countries of origin, transit, and destination in these causes and their regionalization. All these factors together indicate the immediate need to open a regional humanitarian corridor that recognizes the right to free transit for these youth and their families, including special transitory measures of protection and the recognition of the right to refuge or asylum, toward the end of reunification with their families.” As the document explains, it must be a priority to recognize the right of migrants to free transit, so that they can cross Mexico legally, thus averting victimization by violence. Members of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have called on the governments of both countries to recognize these persons as refugees: “The U.S. and Mexico must recognize that this is a question of refugees, thus implying that these migrants should not be automatically returned to their countries of origin but must instead receive international protection.”

More generally, some organizations such as Mesoamerican Voices have emphasized that it is necessary to recognize a transnational citizenship involving rights and obligations—one that not be limited to a single national space. To acknowledge migration as a right is fundamental because, as Amnesty International notes, “the absence of juridical status for irregular migrants implies that they are denied the right to access the justice system. This situates irregular migrants in great danger of suffering abuses.” For this reason, as Pope Francis declared in his August 2013 Message for the Global Day for Migrants and Refugees, “It is necessary that everyone change their attitudes toward immigrants and refugees, from a defensive and suspicious view that perpetuates indifference and marginalization -which in the end corresponds to a ‘culture of rejection’- to an attitude based in the ‘culture of meeting,’ which is the only way of building a more just and fraternal world.”

To favor this “culture of meeting” would imply allowing these persons to move about freely and, instead of investing in deportations and border security, investing in policies to combat violence, violence, and corruption in these migrants’ countries of origins, so as to reduce the “push” factors. In the U.S., some organized migrant groups share this view. For example, the National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities (NALACC) has affirmed that “the organizations of immigrant communities based in the U.S. recognize the transnational nature of this challenge: while we work for change in the U.S., we cannot forget how important it is to promote conditions of greater stability, better health, better education, greater democracy, and better security in sender countries. These conditions could reduce the factors that drive migration and make countries of origin more attractive for an eventual return of many of the migrants originally from these countries who now live in the diaspora.”

Indeed, the migrants we interviewed in the Palenque Migrant Home confessed that they did not want to spend their whole lives in the U.S.: “That is not our land; we only want to work there for a year or two, just enough to save a bit of money to be able to pay for our children’s schooling and to build a house—nothing more. We only want to have the right to stay for a while and then to return to our country.”