LATEST: Mexico – Teachers Return to Class, Disagreements Continue

09/01/2017

ARTICLE: “WE DID NOT CROSS THE BORDER, THE BORDER CROSSED US!”

09/01/2017From August 29th to September 7th, two representatives of the United Nations (UN) Working Group (WG) on Business and Human Rights, Pavel Sulyandziga (Russia) and Dante Pesce (Chile), made an official visit to Mexico that included the states of Mexico, Jalisco, Oaxaca, and Sonora.

However, the impact of human rights on the part of companies not only occurs in these four states: the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) in its communiqué “May the Earth Tremble at its Core”, denounced 27 examples of abuses that illustrate “the storm and the capitalist attack which never lets up. It becomes more aggressive everyday such that today it has become a civilizational threat” The visit raised a number of questions about the role of the WG and its possible impacts.

The WG was formed in 2011 to implement 31 Guiding Principles – contained in three pillars – approved by Mexico and the other 192 countries of the UN Human Rights Council. The first pillar is the obligation of the State to protect human rights through its regulatory framework and public policies. The second pillar is the responsibility of companies to identify where there are potential negative effects in their activities and to take preventive measures to avoid them. The third pillar serves to repair the damage caused.

The Mexican government has defined “to guarantee the respect and protection of human rights and the eradication of discrimination.” as a main objective of its National Development Plan 2013-2018 (NDP) In this context, and under strong pressure from civil organizations to meet with the defined pillars, the WG was invited.

Violation of the regulatory framework to ensure respect for the rights of peoples

Both nationally and internationally, there are rules that establish the right to consultation and due diligence. Convention N° 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), ratified by Mexico, declares that the State has an obligation to consult with indigenous peoples whenever legislative or administrative measures that may directly affect them are envisaged. Due diligence consists of making a prior assessment of the actual or potential negative impact or consequences that business activities may have. In particular, the Environmental Protection Act determines that for every new project, it is mandatory to submit an environmental impact assessment. However, there are numerous projects that do not meet this requirement.

The report, Mexico: Business and Human Rights, carried out by a coalition of more than 100 key organizations, indicates that the main human rights violations related to companies are due to an inadequate, or even non-existent practice of those processes in the design and implementation of large-scale projects. These are mainly mining, energy, infrastructure, and tourism projects. At the same time, civil organizations have accused the National Institute for Access to Information and Protection of Personal Data (INAI in its Spanish acronym) of “simulating transparency”.

Massive increase in violations of human rights of community defenders

The Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA in its Spanish acronym) reported a 990% increase in attacks on environmentalists in less than five years, including personal, telephone or electronic threats, physical assaults, arbitrary prosecution, illegal detentions during demonstrations or on public thoroughfares, murders, defamation, as well as improper use of public force. There are many examples that can be given.

Currently, in Mexico there are 31 wind farms installed, 12 of them in the municipality of Juchitan. For indigenous communities in the area, the consultation process (2015) for the Wind Farm Project in Juchitan de Zaragoza, Oaxaca, was flawed, since the Energy Secretariat had already given a permit to generate power to Eolica del Sur since January 2014, and windmills were already installed in the region. According to the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Project (ProDESC), there was no real consent, given that less than 1% of the affected population was involved. An injunction stopped the project, but in August, 2016, after a review, it resumed. The Popular Assembly of the Juchiteco People (APPJ in its Spanish acronym) is seeking the intervention of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) although they are “aware of the risk involved in defending our rights.” At least thirty attacks against opponents of the project have been recorded: “Those of us who oppose the dispossession of our territory face threats, insults, physical attacks, as well as their relatives, attempts at kidnapping, persecution, defamation, harassment, gunshots outside the houses of our compañeros.” The Articulation of the indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of the Territory has denounced collateral damage of the wind farms: health effects with an increase in deafness, tachycardia, headaches and fainting, malformations in livestock production and a shortage of fish, with fishing being the main source of subsistence in the area.

For its part, the Otomi-Mexica indigenous community of San Francisco Xochicuautla, State of Mexico, has organized against the construction of a road on their land. After submitting a petition to the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH in its Spanish acronym) and the IACHR, both institutions requested the State of Mexico to adopt precautionary measures. Despite these measures and an injunction, the work begun, with the approval of state and federal authorities. In April, hundreds of police invaded the community to protect the entrance of machinery that demolished the house of Otomi leader Armando Garcia. “It was without warning (…). All our belongings were left under the rubble. I mean, we have nothing. And that’s the sad thing that they take you out of your house, practically as if you were a delinquent.” Five other homes were knocked down and several cases of intimidation against opponents have been reported. It should be noted that the Higa group, of Australian origin, in charge of construction, ignored the invitation of the WG to talk during its visit.

Of the projects with the most violent social effects, the extension of the Mexico City International Airport stands out. Since it was launched, there have been deaths, as well as criminalization and prosecution of opponents. In a Contra Linea article, it is recalled that in the first drive for this project, with Vicente Fox at the head of the federal government and Peña Nieto as governor of Mexico, “on May 3rd and 4th, 2006, a police operation was carried out in San Salvador Atenco, which left two dead (…); 209 detainees, including minors and women, several of whom were physically and sexually assaulted.”

Among the strategies to weaken and dismantle initiatives in defense of the Earth and territory, the campaigns of undermining and discrediting those who lead them are noteworthy. In September, in Chicoasen, Chiapas, ejidatarios organized against the construction of the Chicoasen II dam (extension) and denounced that they were being blamed for crimes they did not commit in order to stop them and “wipe out the opposition.” In 2015, their attorney was imprisoned for an alleged offense of rioting. They indicated that Governor Manuel Velasco Cuello “has, through deception and the use of force, imposed this mega-project without taking into account the serious violations of our rights of guarantee and judicial peace and as a way of imposing it, they use acts of threats, deceit, unjustified imprisonment, reprisals and criminalization. “

In Guerrero, the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposing the Parota Dam (CECOP in its Spanish acronym) marked 13 years of resistance against a project that provides for the construction of a mega dam on the Papagayo River to supply the hotel zone in Acapulco. It will involve flooding thousands of hectares of ejido communities, the eviction of 47 communities and 19 ejidos, and the desertification of the lands of those who live downstream (more than 80,000 campesinos). Over the 13 years, both the CECOP and the organizations that have accompanied it have been threatened and attacked. Their spokesperson, Marco Antonio Suastegui Muñoz, was inmprisoned for 15 months between 2014 and 2015.

Another example: in 2009, Mariano Abarca Roblero, who headed a movement against mining carried out by the Canadian company Black Fire in Chicomuselo, Chiapas, was assassinated. His relatives have directly denounced Black Fire arguing that he had received death threats from company workers. Chiapas Paralelo reported that “in addition to being involved in the murder, the Canadian company violated environmental laws, threatened, beat, and tried to bribe Mariano Abarca through their representatives.” Mariano’s family and the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (Rema) continue to demand justice.

Isolated “victories” that do not cause structural changes

The Me’phaa indigenous community of San Miguel del Progreso, municipality of Malinaltepec, Guerrero, managed to stop the entry of two mining companies that had concessions for 168 thousand hectares in their territories. They obtained an injunction in 2014 through an “unprecedented sentence,” according to Desinformémonos, which considered that their rights “were violated by the federal government, after it gave mining concessions to transnational companies without first consulting the inhabitants.”

The community then directed its struggle for the declaration of unconstitutionality of the Mining Law itself, which has not been achieved to date. The Tlachinollan Human Rights Center said that the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN in its Spanish acronym) was prevented from studying this unconstitutionality, pointing out that “transnational companies, the Mining Chamber, and the Ministry of the Economy sought to avoid the analysis of The Mining Law before the SCJN (…) they opted to operate the cancellation of the concessionary titles.”

Violations of labor rights

Although most cases of human rights violations by companies are linked to dispossession of land and territory, employees also face serious violations of their labor rights. The WG highlighted the precarious situation of temporary workers, informality, lack of access to social security, low wages, and a minimum wage that is at a level below basic living expenses.

Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero face the greatest problems of informal labor: income and the link with health institutions, pensions or social benefits are very low. One of the consequences is the impossibility for young people to study. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “more than 50% of young Mexicans do not complete the upper secondary cycle, the highest percentage of the 34 OECD countries.”

In 2015, Mexico ratified ILO Convention N° 138 on Minimum Age for Admission to Employment, set at 15 years of age. However, it is not being respected: some 2.48 million children in Mexico participate in an economic activity, of which more than 1 million (41.1%) are under 15 and 900,000 (36%) do not attend school.

Strong discrimination in the workplace

Workers face many types of abuse of their rights: discrimination, harassment, sexism, homophobia, injustices in pay, positions, and benefits. In its report entitled “Extreme Inequality in Mexico”, Oxfam states that “far from being the only determinants of unequal power relations, gender and ethnic identity are important social categories that constitute discrimination and privilege.” As an example of the wage gap, “indigenous-speaking workers in the agricultural sector earn less than half of what a non-indigenous worker earns in a day.” The WG reveals the “dramatic situation” of agricultural laborers and migrant workers from the south to northern Mexico, noting that more than 800,000 of them receive no remuneration, while another 750,000 earn only the minimum wage or less.

Despite the existence of a National Council for the Development and Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities and a General Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (2011), it seems that little effort is being made to recruit them.

In terms of gender, discrimination in employment is a serious problem. Between 2011 and 2016, the National Commission for the Prevention of Discrimination (CONAPRED in its Spanish acronym) received 1,726 complaints filed by women, of which 73% refer to acts of labor discrimination. Twenty percent of women reported having been subjected to sexual harassment at their workplace, while 15% had been forced by their employers to submit to pregnancy tests. Discrimination against women is also reflected in the low number of women in decision-making positions, both in the public and private sectors.

An unfulfilled labor regulation system

According to Animal Politico “in Mexico, although there is a very rigid regulation of labor markets, the laws are not fulfilled.” Developing a more effective and efficient justice system that enforces the law would be the first step to seeing a change in question to labor. In some of the local boards it has been found that 30% of workers who are considered unfairly dismissed do not sue because of the uncertainty of the outcome and the duration of the process. 57.2% of the active population work in the informal sector.

The hypocrisy of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

There are several large national and multinational companies established in Mexico that are honored with having socially responsible business practices. However, CSR is often confused with philanthropy, reducing “socially responsible” activities to purely assistance features, leaving aside, among other things, respect for workers’ rights. The companies that are promoted as leaders in social responsibility such as Bimbo, Televisa, or Coca-Cola, for carrying out activities like reforestation or opening schools, are also the ones that receive the majority of complaints for violations of human and social rights.

Trade unionism in Mexico: an obstacle to protection

According to Sin Embargo, only 16% of the salaried population belongs to a trade union organization and, of these groups, the majority are “ghosts“; that is to say, they exist only on paper and do not represent the demands of the workers. “It is a tragedy, a humanitarian labor crisis, because there is no one to defend the workers, they are alone, the trade union centers do not defend them nor are the local councils a good endorsement, for their delays, for the corruption, the lag”, says Saúl Escobar Toledo, of the National Institute of Anthropology and History and author of the analysis “Work and Workers in Contemporary Mexico”.

As regards to the independent unions, only about 400,000 workers are affiliated. The WG was alerted to the restrictions on freedom of association of workers and to obstacles to the exercise of freedom of association in the face of threats of dismissal from those who set up independent unions. In 2012, the government of Enrique Peña Nieto proposed a new labor reform. The trade unions were against it. However, Proceso magazine stated that their protest is not to support the rights of workers, but not to lose their privileges as unions, particularly so-called “protection contracts”, the “tripartism” in labor lawsuits (which gives considerable power in contractual disputes) and the existence of the Conciliation and Arbitration Boards, where a network of corruption has been woven.

Recommendations of the Working Group

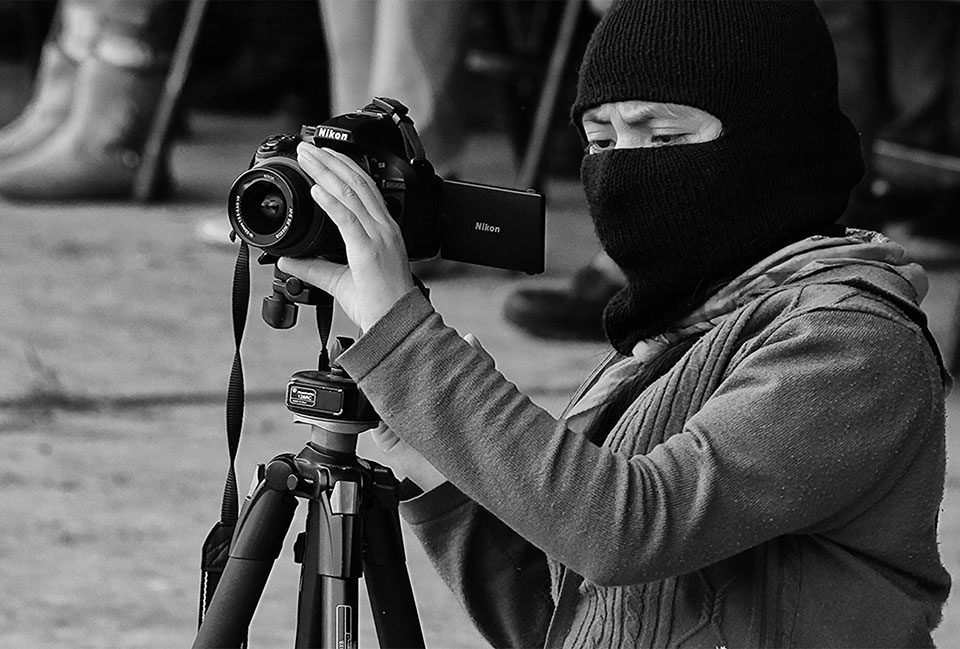

The WG noted the absence of a coherent framework for due diligence and inadequate implementation of laws and regulations; a problem that is aggravated by the complexity of the superposition of competencies of the three levels of government (federal, state, and municipal). It emphasized the limited ability of the competent authorities to carry out inspections to control environmental pollution produced by companies. It also stressed the need to design and implement effective consultation mechanisms with all key actors, strengthening a culture of social dialogue. In a multicultural country like Mexico, it expressed that this dialogue should include, especially, indigenous peoples. It noted evidence of censorship and sanction against journalists who have exposed conflicts of interest and corruption, cases that remain in impunity. Therefore, it considered that there is a real need to restore confidence in the legal system.

It called on all companies to make a greater effort to “uphold human rights standards and avoid seeking to benefit from impunity, corruption and lack of transparency and accountability.” It pointed out that at the international level there is still a need to establish an extraterritorial regulatory framework that allows indigenous peoples affected by the activities of foreign companies to be able to resort to mechanisms of access to justice in the countries of origin of such companies.

Sadly, despite all the recommendations and efforts that could be made, in the case of governments and companies violating the Guiding Principles, no sanction mechanism exists, which opens the door to further abuses and impunity.