ANALYSIS: Current Events – Of changes and continuities

30/07/20102010

03/01/2011In light of the imminent sixteenth Conference of Parties (COP-16) on climate change that will be held at the end of November in Cancún, the International Service for Peace (SIPAZ) would like to share the following reflections on hunger in Mexico and some of the structural causes behind this grave problem, one of them precisely being climate change and its impacts on agriculture in Mexico.

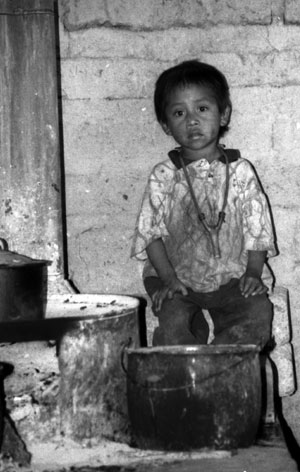

According to the 2008 findings of Mexico’s National Evaluation Council on Social Development (CONEVAL), nearly 49 million Mexicans—over 46 percent of the country’s population—suffered from some form of food insecurity at the time of research. Of these 49 million, 25.8 were subject to what is designated as “light food insecurity,” while 13.7 million suffered “moderate” insecurity, and 9.3 million “severe.”1 Included within these 49 million are said to be 11.2 million individuals who consume less than the line at which CONEVAL marks the base-line of extreme material poverty, in addition to nearly 2 million “chronically malnourished” children2. World-Bank statistics from 2006 show that 15.5% of Mexican children under 5 are stunted by malnutrition; for comparative purposes, this rate compares to a stunting-prevalence of 16.5% among children under 5 in Lebanon, or of 15.7% in Thailand.

According to CONEVAL’s findings, populations suffering from “moderate” and “severe” food insecurity seem to be more concentrated in the middle and southeast of Mexico. CONEVAL’s 2008 report3 also states that 26.3% of the population of Chiapas suffered from either moderate or severe food insecurity at the time of the research. The percentage at that time in Oaxaca was 28.8% and 33.3% in Guerrero. Hunger in Mexico seems especially acute among indigenous groups. Coneval’s 2008 report states that 33.2% of indigenous Mexican children under 5 are stunted from malnutrition.4

Given that the present economic crisis has deepened since the time when the investigations upon which this study was based took place (2008), the current situation today in late 2010 is likely far more severe. The drop-off in remittances from abroad together with the price-inflation and its attendant higher taxes experienced since the onset of the present economic crisis has surely exacerbated food insecurity in the country, as has the increased unemployment rates that have followed from the crisis. For example, a report released in October 2010 by the Strategic Project for Food Security made it known that 4 out of every 10 Oaxacans suffer food poverty, thus making for a drastic increase from the 28.8 found to so suffer in 2008.

Climate change, one of the structural causes for hunger in Mexico

Climate change is a structural factor that already certainly is contributing to the existence and persistence of hunger in Mexico, as elsewhere—and which will undoubtedly contribute to such far more in the future, if the problem is not dealt with in a radically different fashion. Climate change, or global warming, refers to the interference that human activities have had and are having on the Earth’s climate systems since the onset of the Industrial Revolution. It has been more than scientifically established that the mass-burning of hydrocarbons—oil, gas, and coal—since the eighteenth century has caused the Earth’s atmosphere to retain more heat than it otherwise would have; these processes have caused the Earth’s average global temperature to increase by at least 0.7° C since pre-industrial times. 17 countries have experienced record-high temperatures thus far this year.

The warming of the Earth’s atmosphere provoked by climate change threatens potentially catastrophic effects for human society: it will, if unchecked, cause the melting of the polar icecaps and hence cause sea-levels to rise dramatically, radically diminish the availability of freshwater across the globe by causing glaciers to melt away and rainfall patterns to drop off, provoke more frequent and destructive forest-fires, and acidify the world’s oceans. Its first and most evident effect, though, will be a marked increase in hunger and starvation rates, as Jacques Diouf, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization’s director, reminded those assembled at the UN climate negotiations that took place in Copenhagen, Denmark, last December.

In late July of this year Álvaro Salgado, a representative from Mexico’s Network for the Defense of Maize, declared at a Via Campesina conference held in Mexico City that some 14,000 Mexican communities have lost the ability to cultivate maize and beans due to the climate change that has occurred to date. During an observation-mission in which SIPAZ participated in August 2010 (“Water is Life; Let us Defend its Existence”), campesinos from Oaxaca’s central valleys observed that recent years have seen highly diminished rainfall rates. It is estimated that 42 million Mexicans reside in regions that are highly susceptible to drought.

Beyond this, the states of southeastern Mexico have also suffered greatly in recent years due to unprecedented rains, paradoxically another result of climate change, given that a warmer atmosphere retains more water and thus generates more-intense precipitation. Alejandro López Musalem, representatives in Oaxaca of Heifer International, an international NGO that struggles against poverty and hunger on a global scale, calculates that the states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Chiapas will suffer an increase of 20% in the price of basic goods following the recent rains and floods in the near term.

Responding to these ‘natural‘ disasters is a costly endeavor. According to the Secretary for Governance, the federal Mexican government will spend some 24 billion pesos this year in attending to the natural disasters provoked by rains in the southern part of the country. Stephen Lysaght, first secretary of climate change at the British embassy in Mexico, reported in October 2010 that the total cost of responding to the effects of climate change in Mexico could reach 20% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country, if the process now underway is not arrested.

Such problems will only become more acute as climate change continues and begins to accelerate, bringing about significant agricultural decline in those societies that find themselves within tropical latitudes. Estimates claim that agricultural production will simply be impossible in much of Central America if average global temperatures increase by an additional 2° C5 – an eventuality that is entirely within the realm of possibility, given the entirely inadequate response that human society has presented to the problem of climate change6. Given these considerations, surely any means by which to diminish present and future hunger rates in Mexico and elsewhere must include strategies aimed at preventing predicted future climate-change scenarios from taking place.

Use and distribution of land: another factor for consideration

Another factor that is likely hampering the struggle for food security in Mexico is the increasing role granted to agrofuels in agriculture. Agrofuels are the products of agricultural crops—ethanol and others—that are grown to be used as fuel for human transportation—cars, trucks, boats, and planes. They are being hailed in many circles as a viable alternative to the hydrocarbons that have traditionally fueled industrial mass-transportation systems, given questions regarding the political implications of dependence upon petroleum in addition to uncertainty regarding future supplies of such. The main problem with switching to agrofuels, nonetheless, is that the growing of agrofuels competes with the growing of crops for food, and hence that favoring the former would have adverse consequences for the latter. It is also the case that agrofuels require far more water than other crops, so their mass-production would then divert much-needed water for food-crops. Finally, it has already been demonstrated in several countries that a model based on enormous territories dedicated to only one crop (monoculture) implies a loss of biodiversity as well as a loss of the ability of peoples to feed themselves, given that the best lands come to be used for export-crops. Agrofuel production, in the estimation of former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Jean Ziegler (2000-2008), is simply a “crime against humanity.”7

Despite these considerations, the Mexican federal government aims to have 200,000 hectares of its productive lands dedicated to agrofuel production by 20138. The state of Chiapas is estimated to already have some 50,000 hectares dedicated to the production of palm-oil and another 10,000 for jatropha. In July 2010, the Chiapas state-government affirmed its commitment to contributing to the federal government’s plan to provide 1 percent of national fuel demand by 2015 and 15 percent by 2020.

Another relevant consideration is the question of the distribution of agricultural lands in Mexico. As is known, the emphasis placed on the redistribution of land by Emiliano Zapata and his followers during the Mexican Revolution resulted in few actual changes at that time for the states of southeastern Mexico. Agrarian reform produced changes in the north and center of the country, but was carried out in a rather limited way in this region, even after the era of the Revolution. The politicians of the state of Chiapas in particular, many of whom hail from the elite landowning class, promoted the colonization of wilderness-regions in the jungle to avoid having to redistribute existing holdings. This phenomenon has surely diminished with the recent “discovery” regarding the abundant natural resources to be found on such lands, such as water, petroleum, or biodiversity. The politics of “colonization” resulted among other things in the mass-deforestation of the area, with an increase in soil-erosion rates and carbon-emissions. Furthermore, during the last century, the construction of oil-extraction installations and hydroelectric dams have taken out of cultivation large territories of land. All of this has directly affected a large majority of the indigenous and campesino population of the area.

It also bears mentioning that the dietary preferences of many Mexicans together with imposed economic models of “development” may have had impacts on the hunger from which suffer a large part of the Mexican population. Data from 2002 indicate that, on a per-capita basis, Mexicans consume nearly 59 kilograms of meat a year; this is far short of the average for that year for the U.S. (124) or Spain (118), but it is considerably higher than the equivalent to be found in Morocco (20), India (5), or Bangladesh (3)9. It is estimated that about 15 kilograms of grain are needed to produce 1 kilogram of meat. In June 2010 the United Nations urged a global move toward diets free from the consumption of meat and dairy, given the implications of meat- and dairy-consumption rates for world hunger and climate change. In the case of Chiapas, the implementation of a model of development featuring the extensive rearing of cattle in the jungle in the 1980s has had negative impacts both for local food security as well as for the deforestation and soil-erosion implied by such.

Mexican politics and international interests

Another significant factor in the situation of hunger has had to do with economic and agricultural policies that have been implemented in Mexico in general beginning in the 1980s. Since 1988, the option taken by the government of Salinas de Gortari to promote competition and international openness of commerce, brought about important changes in Mexico’s agricultural sector, for they diminished support-programs and resulted in the neglect of the grain-sector, which constitutes the basis for food of the majority of the population. Agricultural production and employment declined. Indigenous and campesino communities that had previously succeeded in producing at least enough for subsistence have increasingly lost this capability. Many farmers in this sense could never compete with the economies of the United States or Canada.

Certainly, the implementation in 1994 of the North American Free-Trade Agreement (NAFTA, with the United States and Canada) has generated serious problems for agricultural production across Mexico, implying a loss of food-sovereignty and contributing to the phenomenon of mass-migration from rural regions, both internally (to large Mexican cities) as well externally—principally, to the United States.

Perhaps it should be noted that the existence of mass hunger today in Mexico, as in human society generally, finds its most ultimate basis in the presently dominant mode of economic organization: that of capitalism. Capitalism is an economic system that bases itself on private property and the accumulation of wealth. The unfortunate result of this economic framework, as the renowned North-American philosopher Noam Chomsky has succinctly put it, is that the interests of profit are placed above those of people, thus resulting in the exclusion of large sections of the population of a given society. Such policies undoubtedly “produce profit,” but this hardly resolves an ever-present question: that of inequality and the distribution of wealth. According to the CONEVAL report previously mentioned, the richest 10% of the population holds nearly 39% of Mexico’s GDP, while the poorest 10% possesses less than 2% of the wealth. This is a reality that practically has not changed since such reports began to be compiled in the 1950s.

Prospects for the Future

As the German social critic Theodor W. Adorno writes, “no other hope is left to the past than that […] it shall emerge from it as something different.”10 Is it nonetheless likely or even possible for there to emerge in the future something “different” than the hunger suffered in Mexico at present? Under most scenarios that will likely come to pass, it seems to be the case that the situation will only get worse.

Recent estimates by the World Bank indicate that the global economic crisis will continue unabated in the coming years11, greatly increasing the number subject to extreme poverty and hunger across the globe. Indeed, the U.N. recently concluded that food prices would increase at least 40 percent within the next decade12. Recent proposals to codify the right to food within the Mexican constitution, though well-intentioned, will not be able to change the present situation, if they do not contribute to changes in prevailing socio-economic structures and power relations. Another challenge in any case is that many of these changes cannot be resolved exclusively in Mexico but rather would demand radical changes at the global level. Although consciousness has grown, the need for global responses to arrest global warming is an example of the challenges to be faced in the future.

These grave considerations notwithstanding, it is still not impossible that this myriad of life-negating realities be overturned—that a world, in Adorno’s words, in which “no one shall go hungry”13 be born from the present. The prospect held out by the Global Scenario Group of what it terms a “great transition” toward a world characterized by liberty, equality, and harmony with nature is theoretically still possible. In many parts of the world, the relationship of indigenous peoples with “Mother Earth,” together with their more-communal manners of thinking and acting, provides us with an example of how to go about remaking the world. We hope that the present situation can be overcome—a task for which each one of us has responsibility.

… … …

- “Inseguridad alimentaria afecta casi mitad del país,” La Jornada, 28 December 2009 (Return…)

- “Desnutridos crónicos, dos millones de niños,” El Universal, 4 May 2010; “23 millones padecen hambre en México,” Vanguardia, 20 March 2010 (Return…)

- Medición Multidimensional de la Pobreza 2008 (Return…)

- Informe de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social 2008 (Return…)

- Mark Lynas, Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, 2008). (Return…)

- Steve O’Connor and Michael McCarthy, “World on course for catastrophic 6° C rise, reveal scientists,” The Observer, 18 November 2009 (Return…)

- George Monbiot, “The western appetite for biofuels is causing starvation in the poor world,” The Guardian, 6 November 2007 (Return…)

- “En suspenso, los planes de biocombustibles; la inversión está frenada: Sagarpa,” La Jornada del Campo, 18 June 2009 (Return…)

- The World Resources Institute (Return…)

- Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life (London: Verso, 2005 [1951]), p. 167. (Return…)

- “Por la crisis, habrá más hambre en los próximos años: BM,” México migrante, 23 April 2010 (Return…)

- Katie Allen, “Food prices to rise by up to 40% over next decade, UN report warns,” The Guardian, 15 June 2010 (Return…)

- Op. cit., p. 156 (Return…)