2010

03/01/2011

ANALYSIS : National mobilization against violence

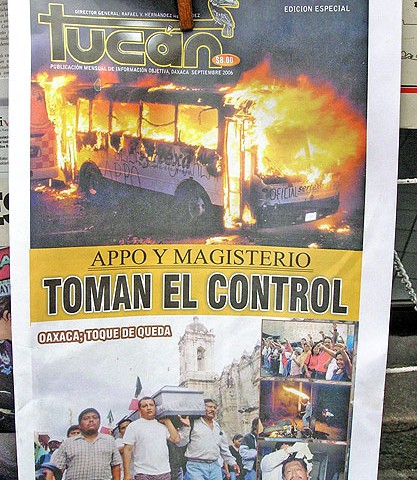

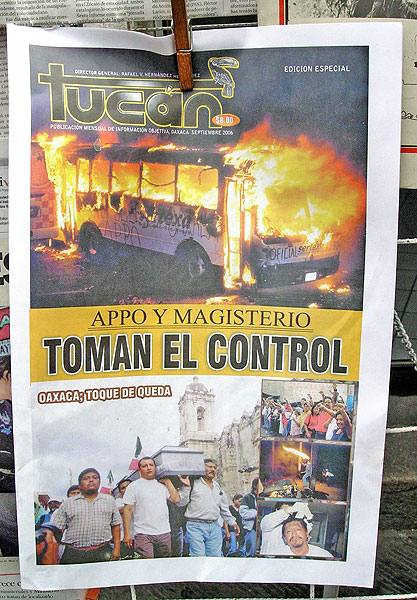

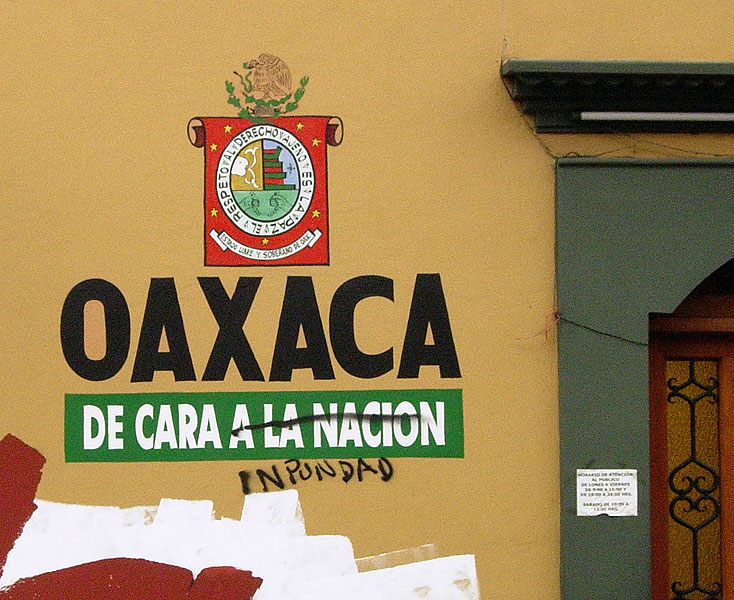

29/04/2011In November 2010, SIPAZ presented a Report during an event organized by the “25 of November Committee for Liberation” entitled “Oaxaca: report on human rights 2006-2010.” Choosing this period for reflection finds its basis in the fact that 2006 was a key year for the state: in June of that year, the violent repression of a sit-in promoted by the state’s teachers resulted in a wave of general protests in Oaxaca and the birth of a largely unfruitful campaign demanding the resignation of Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz (2004-2010). Created during this upheaval was the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO). The political violence and protests continued during the remainder of 2006 until the intervention of the Federal Preventive Police in early November. At least 18 people were killed, with 370 injured and 349 detained during the time that the conflict lasted. Several domestic and international human-rights organizations published reports that provide evidence of a multitude of cases of the excessive use of force, arbitrary arrest, torture, and fabrication of charges against protestors. In 2009, a special investigation carried out by the Supreme Court of Justice in the Nation (SCJN) recognized the responsibility of high-ranking officials of the State with regard to human-rights violations that were committed in 2006 and into 2007. Regardless, essentially no municipal, state, or federal authority thusly characterized has been held accountable for these actions.

On the other hand, 2010 could also be said to constitute an important year for Oaxaca: On 4 July, the “United for Peace and Progress” Coalition, comprised of the PAN (National Action Party), PRD (Party of Democratic Revolution), PT (Labor Party), and Convergencia, defeated the PRI-Green Ecologist alliance, winning the gubernatorial election as well as the mayorship of the state’s capital and the majority of the posts in the state congress. These elections put an end to 80 years of PRI power in the state. Gabino Cué Monteagudo, the new governor who took charge of his office on 1 December, has promised to respond to the questions that arouse worry with regard to human rights in the state. These worries were summarized in an open letter by Amnesty International published on 10 December in which the organization highlighted four major problems: the abuse of undocumented migrants, the attacks against human-rights defenders, the situation in the Triqui region, and the impunity for rights-violations as regards the crisis of 2006.

Impunity in Oaxaca: A look back at the damage done

Impuntiy is a problem that has been emphasized recurrently in the case of Mexico in general, where more than 98% of crimes go unpunished, as has been reported on several occasions from a number of different sources. In the case of Oaxaca, this reality can be seen in different themes or zones of the state.

A first dimension of the problem derives from the impunity that exists in the cases linked to the social conflict of 2006-2007. In a bulletin released in October 2009, the International Civil Commsission of Observation of Human Rights (CCIODH) summarized the events of 2006-2007 in these terms: “selective detentions of social leaders, kidnappings and illegal detentions, threat of arrest-orders often lacking bases, forced exile due to death-threats, mass-detentions and prolonged incarceration of hundreds of people that finally were exonerated of all crimes, torture, rape, defiance of common-law courts in the application of protection granted by federal judges, false accusations against members of the movement so as to protect public officials […] and dozens of homicides with clearly political grounds […] have never been resolved by the state and federal justice system.”

Following the most difficult years of 2006 and 2007, with massive human-rights violations, a number of selective attacks against rights-defenders and social activists have continued, some of the most recent ones being the murder of Heriberto Pazos Ortiz, from the Movement for Triqui Struggle (MULT) and of Catarino Torres Peresa, of the Committee for Citizen Defense (Codeci), both of which took place in October 2010, or of the state leader of the Democratic Cardenist Campesino Center (CCCD), Renato Cruz Morales and his escort (January 2011). In 2009, the international organization Peace Watch Switzerland released a report entitled “Diagnostic on the Situation of Human-Rights Defenders in Oaxaca” in which it finds that “none of the cases that have to do with human-rights violations or aggressions, attacks, or death-threats against such has been investigated or punished. On the contrary, total impunity continues to prevail, and amidst this climate of impunity attacks and rapes continue.” In several cases (for example Marcelino Coache, trade-unionist and APPO activist or Alba Cruz, lawyer), death-threats, intimidation, and harassment go on unchecked despite the ordering of precautionary measures by the Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACHR).

Furthermore, during the past four years, officials in the state have continued to maintain impunity with regard to the new attacks that have occurred against journalists. Perhaps the case best-known outside of Oaxaca is the murder of Brad Will, a documentarian and Indy media correspondent who was killed on 27 October 2006. His family has denounced the manipulation of the investigations, claiming that state officials are possibly involved. A significant point in the case is that the only person arrested for the crime was Juan Manuel Martínez Moreno, an APPO member—this against the evidence and testimony that indicated public municipal officials to be responsible for the act. With the release of Martínez Moreno, the case returned to its initial status, that of impunity.

Another large block of aggressions and murders in different regions of Oaxaca are seen in cases derived from agrarian conflicts that seem at times to be ancestral in which the presence of local cacique interests make learning about such difficult and resolving them even more so. According to data from the state congress, Oaxaca is one of the Mexican states with the highest number of agrarian conflicts. 340 agrarian problems have been reported, of which 127 are deemed critical and can be considered as making-possible social conflict, while 14 are considered red-alerts. In this problem is seen the vicious cycle of impunity that engenders more violence that itself continues to go unpunished.

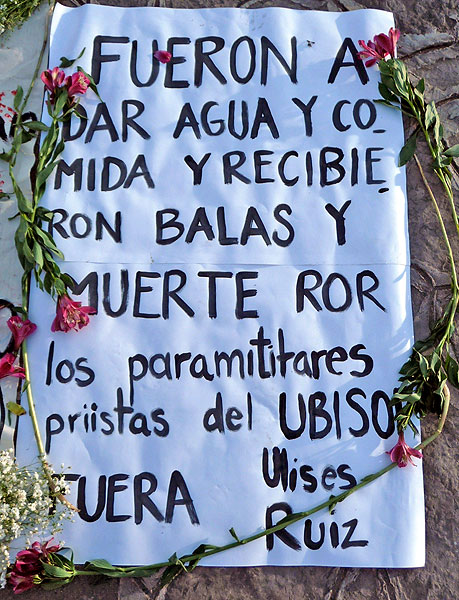

In the most recent cases that have received the most media coverage, the 27 April 2010 attack on the humanitarian caravan en route to San Juan Copala in which were killed Bety Cariño, director of the Center of Communal Support Working Together (CACTUS), and the Finnish human-rights observer Jyri Jaakkola shocked national and international public attention, bringing attention to the Triqui region. Certainly the region has for several years suffered high levels of violence within the context of the political, social, and economic control of the region. Murders and multiple human-rights violations remain in impunity. Moreover, the cases of the 27 April murders have not had significant advances, despite having been taken up by the Federal Attorney General’s Office.

Another situation in which impunity presents itself is violence directed against women. The citizens’ report 2008-2009 “Feminicide in Oaxaca: Impunity and State Crime against Women” denounced the growing gravity of this problem, with Oaxaca being one of the states with the highest number of feminicides in the country. The report cogently demonstrated the incapacity of the State to guarantee the life of women, to act according to the law, and to prevent, attend to, and eradicate the practices that bring about the practice. In accordance with the INEGI, 46% of Oaxacan women both married and partnered have suffered violence at the hands of their partners, with more than a fourth (28.4%) suffering “extreme” situations of violence.

Finally, in recent years, the number of cases of assault, extortion, rape, disappearance, and murder of migrants—principally Central American—during their passage through Oaxaca have increased, this at the hands of networks of organized crime and in certain cases implicating state officials. The majority of the cases are not reported for fear that the assaulted would be deported from the country. Amnesty International has denounced that “thousands of undocumented migrants who pass through Oaxaca every year are victims of multiple abuses. Regardless, the state authorities have demonstrated a worrisome lack of decisive, coordinated, and timely action to guarantee migrants access to justice and protection.”

Insufficient responses to combat the problem from its roots

Following her visit to Mexico in October 2010, Gabriela Knaul, UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Teachers and Lawyers, stressed that “Practically all the actors with whom I have conversed have referred to a deficient system of investigation of crimes and integration of criminal investigation, which allows that the great majority of committed crimes go unpunished.” She added that “[i]f it is true that corruption affects in different ways and intensity different institutions to which I have referred, in accordance with the provided information, the measures of combat against corruption have not been sufficient to eradicate the phenomenon that continues to deteriorate the credibility of diverse actors in the justice system.” While these comments refer to the prevailing general context of Mexico, they are certainly applicable to the case of Oaxaca. In an October 2009 press release, the CCIODH denounced that “The ascent within the judicial or political hierarchies of persons with responsibility in the investigation and protection of human rights who attend more to political commitments than to their true responsibilities and competencies is a challenge for authentic justice.”

In July 2008 the leader of the Managers’ Confederation of the Mexican Republic COPARMEX described the climate that prevails in Oaxaca in these terms: “Here can be killed two young indigenous journalists and nothing happens; they can kidnap [people] and nothing happens; they can enter to rob a house and nothing happens; they can engage in criminal activities and nothing happens.” The omission and absence of responses and advances is the primary expression of impunity. This expression is translated into a lack of action with regard to prevention (a clear example of which being the Triqui region). As Amnesty International indicates in its report on rights-violations in 2006-2007, “the lack of diligence on the part of investigators is a key obstacle with regard to doing away with the general impunity that is seen in the systems of public security and penal justice in Mexico.”

There have also been responses that do not end by breaking with the status quo, for example in the case of the recommendations made by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights following its visit to Oaxaca in summer 2007 that resulted in the reforming of the State Commission on Human Rights, the reforming of the State, and the attention to some particular cases. But the arbitrariness of the releases of the incarcerated could be questioned, as could the detentions: those released did so through negotiation and political pressure, not by means of the efficiency of the justice apparatus. In all cases justice and reparations continue to be lacking.

Another response that did not end up being an advance was the polemical decision by the Supreme Court of Justice in the Nation (SCJN) in the case of Oaxaca. A good beginning can be said to have been seen when the SCJN declared in 2007 that “[w]e cannot permit that arbitrary detentions and torture of prisoners return to being ordinary and normal [acts] in our country… Oaxacans suffered and perhaps still suffer a state of emotional and juridical uncertainty… It would be logical that the people live in anxiety before authorities who use public force without limits and deny the human rights that our juridical institution recognizes.” But the conclusions of the process were at the very least limited: the Supreme Court certainly ruled that Ruiz was responsible of grave violations of human rights in Oaxaca in 2006, but neither criminal charges nor impeachment-proceedings were brought against him, leaving this responsibility to the state congress.

The possibility of a political judgment against Ulises Ruiz was opened in July 2010. Regardless, from the start representatives from the PAN, PRD, PT, and Convergencia characterized this initiative as a “simulated political judgment” that featured large legal loopholes. The process resulted in an exoneration of Ulises Ruiz, due to the fact that the majority of representatives in the state congress continued to be part of his party (the PRI) until the end of 2010.

© SIPAZ

It should finally be said that in more than one case the federal government could be said to hold responsibility both for its actions and its omissions. In a recent appointment with the representative of the Unity for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights of the Secretary of Governance, we were told that some 40% of the cases presently being investigated by this institution are located in Oaxaca. Regardless, a difficulty is that a kind of “passing of the buck” is seen among different levels of the government. When it is convenient for the Federation to do so, it recognizes the autonomy of the states. The states can also distance themselves in other cases, indicating that it is federal responsibility (with regard to militarization, for example). In any case the federal factor is an element to be kept in mind as regards the designing of strategies of defense, in particular because the potential for resolutions by domestic justice institutions must be exhausted before cases can be presented in international platforms such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

From civil society, one of the difficulties regarding impunity is that history continues, and that the cases of today must be added to those from before. This is one of the many challenges that remain for the future: how not to succumb to forgetfulness in light of present exigencies, how to continue struggling against impunity and responding to the new cases that continue to crop up without entering a solely defensive logic, without paralyzing oneself in the end. Presenting us with an example are the efforts of ex-prisoners detained in 2006-2007 who continue to organize themselves and struggle to obtain justice and reparation. In observation of the burial of Beatriz Cariño, this approach was also affirmed in spite of pain: “we will not bury her. We will instead sow her, because she is of the most beautiful flowers. Her example will bear fruit.”