UPDATE: Mexico – Legislative agenda: one step forward, several steps back

02/04/2018

ARTICLE: Jtatic Samuel Jcanan Lum Recognition Award – “we will be the ones below … those who will build a better tomorrow”

02/04/2018From November – to 1-, 2017, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, indigenous from the Philippines and United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, paid an official visit to Mexico She held meetings in Mexico City and in the states of Chiapas, Chihuahua and Guerrero, both with representatives of indigenous peoples and with civil society organizations, government officials, the National Electoral Institute (INE) and members of the National Commission of Human Rights (CNDH in its Spanish acronym). In a collective effort, Mexican and international civil organizations, communities and collectives prepared two reports on the current situation in the country. This focus takes up statements made in these reports.

What was the purpose of the visit?

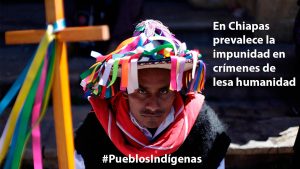

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

The Special Rapporteur is in charge of investigating issues related to human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous peoples. Her visits to different countries serve to raise awareness of the challenges faced by indigenous peoples and alert the world community when they are victims of violations of their rights. The purpose of the visit to Mexico was twofold: to examine the implementation of the recommendations made by the previous special rapporteur, Rodolfo Stavenhagen in 2003, and to assess how the country has incorporated its international human rights commitments in relation to indigenous peoples.

Mexico: between cultural and natural riches and poverty

Mexico enjoys great cultural and natural wealth diversity. Its indigenous population represents 10.1% of the total population of the country and according to the Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI in its Spanish acronym) there are 68 different indigenous languages. Its territory is home to between 60% and 70% of the known biological diversity of the planet. Oaxaca, Chiapas, Veracruz, Guerrero, Yucatan and Michoacan are the states that concentrate the greatest biodiversity and at the same time are those with the greatest indigenous presence. This is not a coincidence, as it is the indigenous peoples who have played a key role in the conservation and protection of ecosystems. Despite the cultural and natural wealth present in the territories of indigenous peoples, this sector of the population suffers extreme economic inequality. According to Oxfam, the poverty rate of indigenous people is four times higher than the average.

It is undoubtedly in the analysis of access to economic, social and cultural rights where the situation of exclusion and discrimination suffered by indigenous peoples and communities is most visible. Structural discrimination is evidenced by the lack of access to basic services such as drinking water and drainage, health and education. In many indigenous communities, rainwater or water from a stream is collected, which involves walking hours carrying heavy vessels filled with water. This discrimination is also seen in the high levels of infant and maternal mortality rates: twice as high among indigenous women as among non-indigenous women.

Internal policies and structural reforms that are detrimental to the rights of indigenous peoples

Press conference of the Rapporteur organized within the context of the visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples © SIPAZ

According to reports, the Mexican legal system is being modified to attract investment and promote foreign trade at the expense of respect for the rights of indigenous peoples. The latest reforms adopted in Mexico were regressive given that the interpretation of concepts such as “public utility” or “social interest”, which had been conceived to protect the general interest against private interests, now favors national and international private interests. The energy reform of 2013 opens up the possibility for companies to promote the establishment of servitude, that is, to obtain the right to use and temporarily occupy the land of their interest, even though they are ejidos, communal goods, private properties, indigenous and/or campesinos communities. This servitude can be obtained legally through the courts or with the support of the Secretariat of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU in its Spanish acronym) and the Secretary of Energy (SENER in its Spanish acronym) through administrative channels.

Another example is Article 19, Section VI, of the mining law which guarantees the industrial use of water over human and domestic consumption, which undermines the human right to water contemplated not only in the Mexican Constitution but also in the International Agreement on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ratified by Mexico.

“The Mexican State not only does not comply with its obligations to respect and protect the rights of these populations, but it also becomes a facilitator for companies to violate the rights of communities”, claim the authors of the report on the situation of the rights of the indigenous peoples that was given to Rapporteur Victoria Tauli-Corpuz. However, despite all the complaints issued, the Mexican State has not demonstrated its willingness to engage in meaningful and long-term dialogues that allow indigenous peoples and communities to participate in decisions and the establishment of administrative and legislative measures that affect their population, territories and rights.

Territory: another right denied

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

The lands and territories of indigenous peoples are not delimited or legally recognized. This situation generates conflicts of two types: on the one hand, between different indigenous communities that declare themselves the owners of the same land. This is the case, for example, in the conflict between Chenalho and Chalchihuitán in Chiapas, which has lasted for more than 40 years. At the end of 2017, it was violently reactivated, generating the forced displacement of more than 5,000 people. To date, more than 1,000 people remain in this situation of displacement (see Analysis). On the other hand, it produces cases of dispossession promoted by the economic model. In effect, the rich natural resources present in indigenous territories are a source of interest on the part of outside players: the Mexican government as well as large national and international companies. The colossal economic profit that the exploitation of water, minerals, hydrocarbons and timber can generate encourages these actors to implement their projects at all costs. “National and international companies operate without attachment to human rights or environmental and social impact assessments in accordance with international standards. The lack of adequate public policies, the crisis in the agrarian sector and the legal advantages for investment to the detriment of social rights engender regressive, harmful and actions that are incompatible with the obligations of the State in the question of human rights.”

In order to obtain legal recognition of their territories, native peoples require legal titles, which are usually denied or delayed by the authorities at the time of undertaking this process. “Government programs, such as PROCEDE or FANAR, are disguised as regularization processes for agrarian groups that do not have property titles, to grant certificates of land ownership, which in reality permit opening the way to megaprojects, given that they facilitate the purchase and rent of lands.”

Another way to dispossess and displace indigenous communities is the declaration of Protected Natural Areas (ANP in its Spanish acronym). In this case, the access of indigenous peoples is restricted and they are prohibited from making use of natural resources. However, concessions are granted to companies to develop tourism projects, clearing forests and extracting minerals in those areas. The reports state that the lack of elaboration and/or publication of the management programs of the ANPs of federal competence allow transgressions of human rights to a healthy environment, legal security and legality. These APNs are revealed as simulators of biodiversity protection but in reality have a negative impact on the conservation of ecosystems.

Defense of land and territory repressed

Dissemination campaign in the framework of the visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples © Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center

Survival is the greatest challenges facing indigenous peoples today. Historically linked to the land as the source of their life and as the basis of their existence as identifiable territorial communities, the indigenous people have fought for a long time to own and conserve their land. Land rights are the most important issue faced by native peoples today. Rodolfo Stavenhagen had already denounced in 2003 the collusion and permissiveness between companies and the authorities that exist in Mexico, as well as the lack of enforcement of legislation and the principles of consultation. In many cases, megaprojects have been initiated without any consultation being carried out with the affected peoples, or only “on-the-spot” consultations have been carried out, that is to say, government simulations in order to appear to comply with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). Such consultations serve to seduce a part of the people with promises of improvement of the living conditions and infrastructures in their communities, of attractive job offers and other economic benefits, causing a break in the social fabric among those who let themselves be cajoled and those who resist. The reports document with multiple cases that the indigenous peoples, when undertaking any mobilization or protest in defense of their territories, become targets of repression, threats, criminalization, harassment, surveillance, aggression or illegal imprisonment and even murder.

To this is added the use of violence and the use of police and military forces to impose these megaprojects and implement them in an authoritarian manner. The Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA in its Spanish acronym) has monitored a total of 303 cases of attacks on these environmental defenders from 2010 to July 2016. It has been possible to define a common pattern where the aggressions are perpetuated against the main leaders and community authorities that play an important role in the defense of rights, which causes a weakening of the defense movements. This situation of vulnerability and insecurity has led to the migration or forced displacement of members of the communities. In 2016, Michel Forst, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, and in 2017 Victoria Tauli Corpuz denounced the violent means of imposing megaprojects on indigenous territories and urged the creation of a mechanism for protection and a guarantee of the right to consultation and sanction in case of violation. However, to date, the Mexican government remains powerless (or unwilling) to implement both that right and the recommendations issued.

The failure of the State to fulfill its role of investigation, prevention and protection has fostered this context of insecurity and violence. It has also been documented that in 43% of the cases of aggression, the authorities themselves have participated at the three levels of government (in 7% by the personnel of the companies and in 2% by organized crime). Leaving acts of aggression unpunished clearly sends the message that more could be committed without any sanction.

Although there is a Protection Mechanism for human rights defenders and journalists, there is a great distrust that it is the State that offers them protection when this same player is the one often identified as the aggressor.

Difficult access to justice

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

Mexico suffers from a lack of harmonization of the country’s institutional structure and the ordinary justice system with indigenous justice systems and institutions, as well as with international human rights standards. In addition, in spite of legislative reforms such as the 2011 constitutional reform on human rights that raises favorable conditions for the right to justice of indigenous peoples, as well as the incorporation of interpreters who know indigenous languages and cultures or the consideration of customs and practices, the governmental authorities do not put these rights into effect.

Taking the example of bringing an injunction (amparo), although it is the procedure most used by the indigenous communities of the country for the defense of their collective rights, is not a simple, accessible and suitable resource. The Injunction Law that regulates it has by no means been conceived so that it can be used by indigenous peoples and communities. It is an extremely complex process since it is a legal procedure that requires the fulfillment of numerous formalities. For example, indigenous communities that have not been recognized as such or as agrarian communities face difficulties in accrediting themselves. Once the obstacles that imply the long judicial processes have been overcome, the resolution of an injunction usually takes years, even whole decades, leaving the indigenous peoples in complete vulnerability and uncertainty as regards their future. In addition, the said resolution may be favorable or not. When a favorable injunction is obtained for those affected, companies can appeal it one way or another and there is no guarantee that they will be respected and obtain definitive and optimal protection in their territories. Possible appeals further prolong the procedure. On several occasions it has been seen that the same project, although legally not approved by a community, is not canceled but only suspended momentarily until it is presented again under another name. On the other hand, there have been cases of violation of injunctions remaining in impunity until today, as in the community of Xochicuautla organized against the Toluca-Naucalpan highway.

Another difficulty is the fact that State officials and institutions in the actions and policies they implement are not assuming their role as guarantors of the rights recognized in the Declaration and international treaties. The inefficiency of the CNDH has been denounced on numerous occasions.

Native peoples also face a lack of available and accessible jurisdictional bodies, given the geographic location of their communities and their economic conditions. The seat of the courts is located in the capital cities, which implies access problems for them. Also, the need to hire a lawyer exceeds their financial possibilities and resources. Although there are non-governmental organizations that propose support for the defense of rights, their response capacity is limited. In addition, communities must present evidence of the afflictions suffered, such as environmental studies that are difficult to carry out and expensive. Evidence from the field of social anthropology is also requested in court cases, in order to demonstrate their cultural relevance and even require proof of their belonging to an indigenous people, thereby violating the right to self-definition and ascription recognized by Article 1.2 of Convention 169 of the ILO and Article 2 of the Mexican Constitution.

Finally, reports indicate that on several occasions, judges who issued rulings favorable to the rights of indigenous peoples and unfavorable to the interests of companies were subsequently moved to other courts.

Specific indigenous groups that are even more vulnerable

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

Within the indigenous population it has been observed that there are some specific groups whose rights are even more affected by their condition: women, migrants, prisoners, victims of forced displacement, and day laborers as well as children. The alarming thing is that the violation of their rights is largely due to federal institutions.

Women are four times more affected by being indigenous, women, poor and coming from a rural environment. In Chiapas, the Center for Women’s Rights (CDMCH in its Spanish acronym) denounced omissions by the bodies that receive the victims. For example, it revealed that there is no channeling of health services to investigate cases when identifying situations of abuse. There were also reports of victims of rape, including minors, who were denied abortion despite the prevailing legislation in these cases. In addition, the services are barely accessible for communities far from the cities and neither do they have translators in indigenous languages nor specialized personnel.

Indigenous prisoners imprisoned arbitrarily are often victims of torture and various violations of due process, their judicial guarantees such as the accompaniment of a translator or interpreter or the actual presence of defense lawyers. At the time of arrest they are not shown an arrest warrant, nor is the reason for their detention presented to them. Years can pass without having any sentence. Inside the prisons they are usually forced to perform forced labor, are extorted, threatened with death, victims of physical and psychological aggression. Conditions of abuse, isolation, ethnic discrimination, lack of medical attention and food, lack of access to drinking water, lack of inviolability of correspondence, unfair transfers to centers that are in charge of federal crimes and many other violations have been reported. In the case that they are granted freedom due to innocence, few manage to have access to compensation for the damages they suffered.

Migrants, on the other hand, suffer victimization on the part of justice enforcement agencies as well as public human rights bodies. The backlog to attend to their asylum and refuge requests usually exceeds the established deadlines for months and even years, leaving them in an endless wait and in a status of uncertainty and helplessness, unable to work legally.

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

Finally, casual laborers, who are at the same time internal migrants, suffer from non-observance of their labor rights, those most frequently violated being stable employment, satisfactory working conditions, freedom of association and collective bargaining of work, social security, prohibition of child labor, forced labor and equality between men and women. There have been documented situations of unjustified dismissals, fraud or undue charges in the recruitment process, exposure to agrochemicals, sexual harassment, housing in overcrowded conditions, strenuous working hours, exploitation and lack of overtime pay. The internal labor mobility programs promoted by the Ministry of Social Development and the National Employment Service do not monitor the recruitment process done by intermediaries by farmers, nor verify the working and living conditions in the workplace.

Conclusion:

Visit of the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples to Chiapas © Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights

In her declaration of the end of the mission, the rapporteur warned that “the inadequate legal recognition in force of indigenous peoples as holders of rights, together with structural discrimination are the basis of all the issues and concerns” in the areas of “lands and territories; autonomy, self-determination and political participation; self-ascription of indigenous peoples; access to justice; violence and impunity; the right to determine their development priorities; consultation and free, prior and informed consent; economic, social and cultural rights, and the particular situation of specific sectors of indigenous peoples.” The final report of her visit to Mexico will be presented to the UN Human Rights Council in September 2018 in Geneva, Switzerland.

In 2003, the Special Rapporteur had recommended to the Government of Mexico that it pay urgent attention to the prevention and resolution of social conflicts in indigenous regions, that the indigenous justice system be thoroughly reviewed and that a comprehensive economic and social policy be developed to benefit indigenous regions with active participation of indigenous peoples and with special attention to specific groups. The purpose of these recommendations was to achieve peace and meet the demand of indigenous peoples for the recognition and respect of their rights.

Unfortunately, the reports that form the basis of this synthesis and the observations of the current rapporteur show that 15 years later the recommendations have not been taken into account and that the situation of vulnerability of the human rights of indigenous peoples has not improved. On the contrary, conflicts multiplied and intensified, the level of violence increased, the level of marginalization worsened and specific groups continue to suffer increasingly serious violations.

Despite having included in its law articles and ratified international treaties that guarantee respect for the rights of indigenous peoples, there is a huge gap between the theory and practice of human rights in Mexico. The Government follows a logic that consists of signing and ratifying all agreements on human rights in order to try to look good abroad, without applying them at home. The organizations that wrote the reports delivered to the rapporteur denounced the lack of political will to address this gap. How many more visits from the UN or how many more complaints will be necessary to finally make a real change?