ANALYSIS : Mexico – Elections and fear that history may be repeated

28/08/2012SIPAZ Activities (From mid-May to mid-August 2012)

28/08/2012“I want justice not just for Itzel, but also for all other women who have been killed in the country and in Chiapas. I demand justice because losing a daughter is a pain that cannot be imagined.”.

During the 52nd session of the committee of experts of the United Nations Convention for the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) held on 17 July 2012, there was an evaluation of the observance of this convention on the part of the Mexican State. Some 50 Mexican civil organizations presented 18 “shadow reports” that contrasted with the official report released by the government. The number of reports was an indication of the dissatisfaction of civil society with regard to the protection of the rights of women, and the failure of the Mexican State to respect international standards so as to promote greater gender equality. In their shadow reports to CEDAW, the civil organizations emphasized that the situation of violence in the country has repercussions on the physical integrity of women. They affirmed that the federal government’s strategy of combat against organized crime has caused high levels of violence against women, worsening the levels of impunity, institutional violence, and discrimination against them. According to Consorcio Oaxaca, the organizations saw it as an accomplishment that the “Mexican State was strongly challenged for the constant human rights violations against women and for not clearly reporting on their actions against gender discrimination.”

According to a report from Amnesty International (AI), also published in July, violence against women in Mexico has not ceased but rather has increased considerably in recent years. This report also affirms that the governmental institutions in Mexico have failed both in their obligation to protect women from increasing violence and discrimination, and in their failure to legally prosecute those responsible. With regard to rape, the AI report mentions that in 2009 14,829 complaints were filed for this crime in all of Mexico, and that of these only 2,795 led to convictions in court. Worse, it stresses that “studies carried out at the national level suggest that only 15 percent of such crimes are reported.”

Gender-sensitive legislation: progress or bureaucracy?

Beyond the UN’s CEDAW, since 1994 in Belém do Pará, Brazil, the concept of “violence for reasons of gender” was included in the agenda of the Organization of American States (OAS) through the Inter-American Convention to Prevent, Sanction, and Eradicate Violence against Women. The Mexican government has signed on to this convention, and so is obliged to develop legislation to comply with it. As a consequence, in 2007 the federal government released the General Law for Access of Women to a Life Free of Violence. Amnesty International considers that the adoption of this law “signifies progress for the creation of a national juridical framework that would recognize and address various forms of violence against women.”

This law also obligates state and municipal governments to take budgetary and administrative measures to guarantee the right of women to a life free of violence. However, according to the 2009 Annual Report of the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC), the law has limitations, given that it lacks elements such as “the design and instrumentation of public policies that avoid the commission of crimes against women, rehabilitation by means of providing specialized and free juridical, medical, and psychological services; and the investigation and sanctioning of negligent acts by authorities that lead to impunity for the violation of the human rights of victims.”

Later in 2009, the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women (CONAVIM) was created to foment reforms at the state level. In March 2009 for example, the Law for Access to a Life Free of Violence for Women was passed in the state of Chiapas, which according to the CDHFBC lacks practical mechanisms of application. The CDHFBC mentions that “many of the prosecutorial officials are unfamiliar with these laws, while others claim to know of them, though they fail to apply them in their juridical arguments. In the judicial branch of Chiapas the same pattern is seen, since judges and magistrates do not hand down sentences sensitive to gender perspectives.” In more general terms, the 2012 Amnesty International report stresses that “the application of said laws adopted in 28 states is often vague, and it leaves doubts regarding the concrete responsibilities of each authority. According to CONAVIM, many state penal codes continue to be lacking.” Similarly, the CDHFBC observes that these laws are often little more than declaratory statements.

Lack of access to justice for the women of Chiapas

The Center for Women’s Rights of Chiapas (CDMCh) and the Group of Women of San Cristóbal de Las Casas (COLEM) presented a shadow report before the CEDAW committee entitled “The situation of discrimination and lack of access to justice for the women of Chiapas, Mexico.” The document deals with the question of access to justice among women in Chiapas, particularly for indigenous and rural women, emphasizing the problems of violence, feminicide, and access to land. The report stresses that “it is of concern that the institutions of justice that exist in Chiapas do not have multidisciplinary teams to investigate these crimes; there are no protocols of action in accordance with international standards; or databases with precise information regarding murdered and disappeared women. The hierarchical,unequal relations based on ethnic and social origins are factors that also transcend the task of prosecution and administration of justice. In some cases, it is the lack of sensitivity and training of officials that revictimizes the victims and survivors, generating more violence and discrimination and inhibiting the filing of complaints.”

In Chiapas, there continues to exist a situation of structural violence toward women due to their lack of access to education and health services as well as employment opportunities. Multiple situations of familial violence are also seen. It requires a great deal of courage and patience to file a legal complaint of a case of violence, given that several examples show that this action can cause repercussions that threaten familial and communal integrity as well as individual physical security. Furthermore, in rural communities, traditions do not favor women, since in the words of Dr. Mercedes Olivera in 2011, it is expected that women put up with violence as an inherent part of life. In her process of field research, for example, a woman from Chalchihuitán expressed that “If the husband is drunk and he beats his wife, his father will scold him, but the woman’s mother will also tell her she should learn to deal with the husband, as this is what is expected of us as women.”

Feminicide: “the extreme form of gender violence”

Despite the advances that have been seen in legislative terms regarding the penalization of violence against women, governing institutions have not been able adequately to protect women; indeed, the number of feminicides has increased in the last three years. Rupert Knox, investigator for AI, declared during the July presentation of the report that “in the last few years we have seen not only an increase in the number of homicides of women, but also a continuous and habitual absence of effective investigations for justice.”

Several states have introduced the category of feminicide into their penal codes. Nonetheless, according to social activist groups, in Chiapas the number of feminicides continues to increase. On 14 July, organized civil society groups concerned with the defense of women’s rights in San Cristóbal de Las Casas held a performance in the Peace Plaza in this city, denouncing the 32 feminicides carried out in Chiapas so far this year. One of the cases that was denounced is that of the Tzotzil youth Itzel Méndez, 17 years of age, whose body was found on 14 April in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, with signs of rape and beating. Martha Figueroa Mier, women’s defense lawyer at the Mercedes Olivera Feminist Collective, noted that “in 2011, the State Attorney General’s Office reported more than 100 murders of women in Chiapas. We have requested that the Office establish protocols of protection for women.”

Regarding the number of cases of feminicides in Chiapas, these data vary according to different sources. According to representatives of the Chamber of Commerce and associations from the tourist sector of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, “in the year 2011 there were two cases of murders of women.” The shadow report for the CEDAW committee put together by the CDMCh and COLEM, on the other hand, stresses that with regard to gender violence and feminicide, “Chiapas finds itself in a very critical stage. So far this year, an extraordinary number of disappeared or murdered women for reasons of gender have been recorded. In several cases, extreme violence has been used, including torture and mutilations.” The statistics of the women’s human rights defenders contrast notably with the statistics put forth by State institutions. The differences have to do with on the one hand the absence of specification of the municipalities included in the data, and on the other with the failure to classify murders of women for reasons of gender as feminicides.

Human rights defenders threatened despite being under protective orders

In their shadow report for the CEDAW, the organization Mesoamerican Initiative of Female Human Rights Defenders declared that “between December 2010 and December 2011, eleven female human rights defenders were murdered, the majority of them from the states of Chihuahua and Guerrero.” A case of violence in Chiapas that continues in impunity is that of the human rights defender Margarita Guadalupe Martínez Martínez. In February 2010, Margarita Martínez was a victim of kidnapping, torture, and death threats aimed at having her drop her criminal complaint of aggressive invasion of her home by police in November 2008. During the subsequent years, Margarita and her family received several death threats despite being under court-ordered protection. Following new death threats received on 30 June, Margarita and her relatives decided to seek refuge elsewhere, leaving the state for an indefinite period of time. It should be recalled that at the time of receiving the most recent death threats, the human rights defender was in the midst of preparing to participate in the 52nd session of the CEDAW.

In other news, in Oaxaca in April, the human rights defender Alba Cruz, from the organization Gobixta Committee of Comprehensive Defense of Human Rights (Código DH), received a death threat to her cell phone. The defender has had protective custody awarded by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for some years now, since she had previously received intimidating messages as well. Another Oaxacan defender who has been a victim of intimidating action, despite also having protective measures from the IACHR, is Bettina Cruz Velázquez, member of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Tehuantepec Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory. In February of this year, the Federal Attorney General’s Office (PGR) arrested her, accusing her of kidnapping workers from the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). Many social and civil organizations pronounced themselves in favor of her immediate release, alleging that the true motive for the arrest was the criminalization of the work of human rights defenders. Bettina Cruz is under court-ordered protection since she was assaulted by state police while she was informing indigenous communities of their rights to the land.

Murders for reasons of gender among the gay and lesbian community

Another type of gender-related violence that has been seen on several occasions in Guerrero in recent years has been the murder of members of the lesbian and gay communities. Despite the fact that, for example, gay marriage has been approved in Mexico City, this serious form of violence continues to exist against these people. On 4 May, a trans person was killed in Acapulco, with the killers unidentified. Precisely one year previously, on 4 May 2011, one of the leaders of the lesbian and gay community in Chilpancingo, Quetzalcóatl Leija Herrera, was murdered. In a May 2012 press conference, José Lavoisiere Luquín Jiménez, another leader of this community, reported that so far this year three homosexuals have been killed: one in Chilpancingo, another in Acapulco, and yet another in Coyuca de Benítez. At the same time, he warns that there is an underreporting of two homicides for every recorded murder: “that is to say, there are nine cases, but these are not registered with the authorities due to the homophobia of relatives or the fear that someone will do something to them.”

Little hope for women under Peña Nieto, rights defenders fear

Following the federal elections on 1 July in which Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) was elected as the next president of Mexico, several women’s rights activists have expressed their concern regarding feminicide and gender violence. In a press conference to report on the Mexican State’s presentation before the committee of experts of CEDAW, María de la Luz Estrada, coordinator of the National Observatory on Feminicide, recalled that as governor of Mexico state (2005-2011), “Peña Nieto refused to have investigations carried out by the National System to Prevent, Sanction, and Eradicate Violence against Women.”

In the same conference, Gloria Ramírez, from the Mexican Academy on Human Rights, mentioned that Peña Nieto also bears responsibility for the women in the case of San Salvador Atenco. In May 2006, in that community in the state of Mexico, 26 women were sexually assaulted by the police after having been detained at a protest. The July 2012 Amnesty International report reports that the case of Atenco “is emblematic,” given that despite the gravity, impunity persists in the majority of these cases. The women who have suffered aggressions, despite the gravity of these humiliating and dehumanizing acts, have been denied access to justice both at the state and federal levels. For this reason, the cases have been taken to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

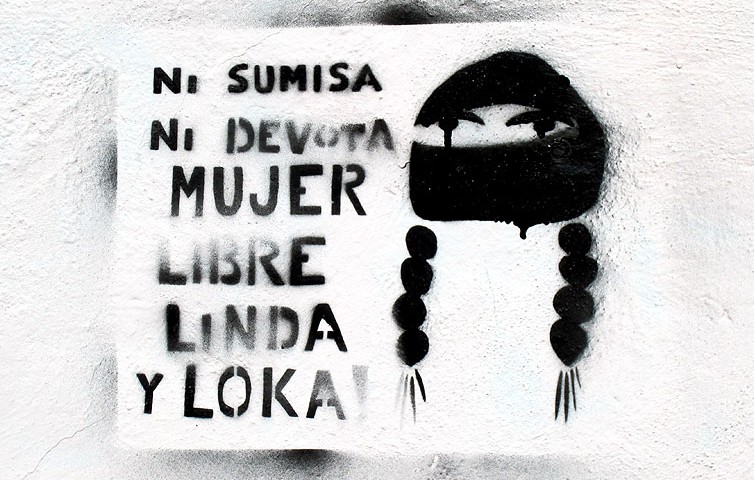

With organized women, more hope for the future

According to the shadow report of CDMHCh and COLEM, the currently existing political and legal system in Chiapas “does not guarantee access to justice to women on equal terms with men but instead totally ignores their particular necessities as a general rule.” The CEDAW committee made a series of recommendations for the Mexican State to improve the situation in the country regarding the defense of women’s rights. Among the CEDAW recommendatons, for example, is to undertake actions to encourage the filing of complaints in cases of violence against women, to accelerate detentions related to violence against women, and to adopt adequate means to prevent, investigate, bring to trial, and sanction violence against female human rights defenders and journalists.

As underscored by the organization Women’s Communication and Information (CIMAC), the number of shadow reports that were prepared for the CEDAW session, besides indicating the gravity of the situation lived by women in the country, is also a reflection of increased organizational capacity of women to respond. And in spite of all that remains to be improved with regard to the situation of women in Mexico, the struggles they carry forward and the small and large victories they have achieved should not be forgotten. Peace Brigades International (PBI) mentions in a book on rights defenders it published in January 2012 that among the most recent successes have been the IACHR sentences in the cases of Inés Fernández and Valentina Rosendo, indigenous women who were raped by soldiers in 2002: “Each one of these sentences is the fruit of the joint work of many people, but it has been these women who with their courage and persistence in confronting pressures, death threats, and even physical assaults, have kept these processes alive.” Additionally, beyond the legal and juridical context, there are an increasing number of women who are emboldened to overcome fear and shame, simply to “speak up” both in the familial context and in public and communal spaces. This is the essential first step toward the realization of many necessary societal changes.