SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-November 2014 to mid-February 2015)

21/02/2015SIPAZ: 20 years accompanying lights of hope

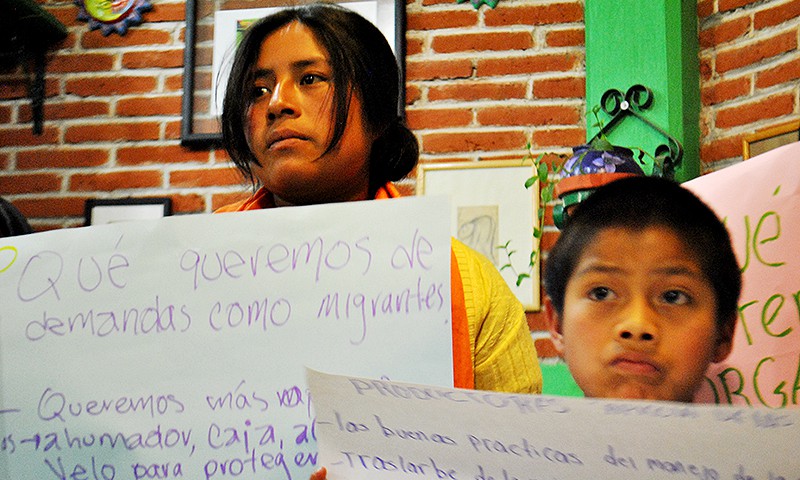

02/06/2015Transnational migration is a sharply expanding phenomenon. Each year, hundreds of thousands of people attempt to cross into the United States in search of work, income, or some type of security that will allow them a better quality of life. Among these migrants who cross from Mexico are Mexicans as well as citizens of other countries, principally Central American, a majority of them undocumented. As the article “In Focus: Central American Migration to the United States – Recognizing the refugee along the ‘infernal route'” (SIPAZ Report, September 2014) discusses, transit through Mexico is difficult and dangerous. On this occasion, we seek to detail the differential impacts these processes have on men and women.

Women who stay

In Chiapas, migration increased after 1994, the watershed year marked by the entrance into law of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This treaty consists in the implementation of a series of neoliberal economic reform measures that exacerbated poverty among majority campesino populations. It is precisely to assure the family’s survival and to satisfy its necessities, such as the right to land and housing, that migration has increased, above all toward large Mexican cities, as well as toward the U.S. Migration has marked the lives of women, both of migrants as well as of those who have remained in their communities following the migration of a husband or partner. In an interview with Mesoamerican Voices A.C., a civil association for action with migrant peoples, we heard their observations regarding these changes.

A situation on the rise is that of women who stay as heads of household when their partners migrate to other parts of the country or the U.S. With the latter absent, it is women who must take on the work both inside as well as outside the home. They must take charge of childcare, maintenance of the home, and the cultivation of the land. Some of them use the remittances sent back to contract day-workers to cultivate their parcels of land, or they open small shops to provide additional income for family subsistence. For these reasons, women’s work and domestic responsibilities increase.

Another aspect to stress is that many women remain under the control of their parents- and siblings-in-law, who do not leave them alone but rather watch them and accompany them on their outings. The emotional impact such surveillance has can only be imagined. They do not have the chance to speak with other women and so share their sadness and pain, thus making difficult to deal with the pain that separation implies. Often they maintain communication with their partners by phone, though this connection tends to break down in the case of alcoholism or drug abuse on the part of the migrant partner, or if s/he begins a new family in their new place of residence. Sometimes with the breakdown in communication comes also a reduction in remittances, which may even stop being sent altogether.

In the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca, many women whose husbands have migrated and who have remained as heads of household have had to take on tasks and provide services to maintain communal structures. In this sense, men’s migration has promoted the participation of women in spaces that have traditionally been occupied by men. In the highlands of Chiapas, this assumption of public duties on the part of women does not take place, as communities have opted for a system of fines to prevent migration, thus forcing men to remain or return to their places of origin to observe their “obligations” to the community. The fines are higher for more important positions, and if they are not paid, migrants run the risk of having the community divest them of membership, whether as ejidatarios, communards, or neighbors. Some choose not to return and so lose their rights, with the result that they, their wives, or their heirs are expelled from the community. In the case of female heads of household who become landless, they often seek out relatives to help them relocate, usually with their mothers. The transfer of debt incurred from these fines to the wives of errant migrants leaves them even more vulnerable.

Women who migrate

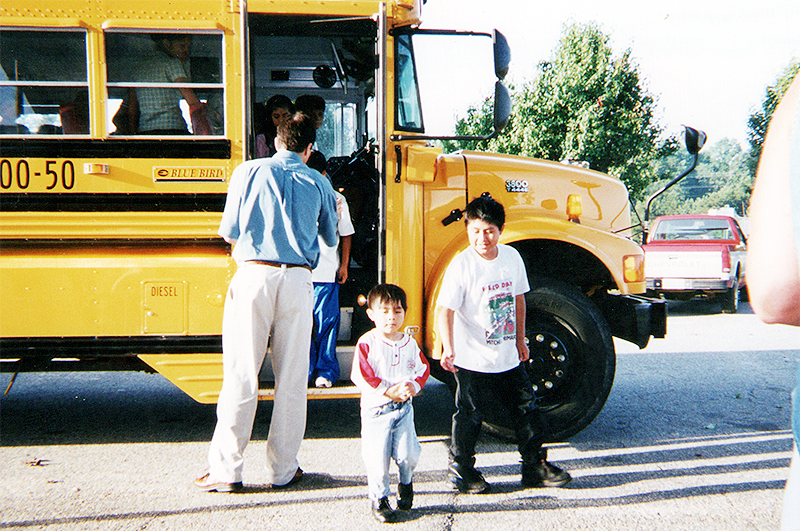

In general, women from Chiapas who migrate have the opportunity to gain different experiences from the routine in their communities. Many of them go of their own volition, without regard to the migration of a partner, but others migrate in response to the suggestion or demand of a brother, father, or partner. Though some migrate with their children, others suffer from having had to leave their children in charge of the family. According to Mesoamerican Voices, many women who have migrated affirm proudly that migration has allowed them to liberate themselves from the control mechanisms of the community and violent domestic relations they had previously confronted. It continues to be common that, following the consumption of alcohol by male partners, females in the family are beaten, both mothers (more commonly) or children, whether boys or girls. Though women generally enter the labor market in exploitative conditions, they also gain greater social autonomy and capacity to choose their life paths by having their own incomes. Some of them, upon returning, can buy land or start small businesses. It is in this sense that migration, whether for study or work, has come to be understood as the right to escape as a conscious decision, as an act of rebellion and disobedience. Indeed, the possibility of migrating is present in the imaginary of the youth: for them, migration often represents an escape valve, a rite of passage demonstrating integration to the realm of adults and providers. The farther away, and the longer the time away, the greater the familial recognition.

Following the experience of migration, many women who have migrated have changed the dynamics of their relationships with men, or their role within the family. Being more autonomous, their contribution to the familial nucleus gives them more recognition within this context. It should be noted as well that some of them benefit from the protective measures that their new places of residence provide them: for example, policies against violence against women, which show them new forms of relating with men.

Another situation to note is that of women who migrate alone and then return to their communities in the highlands of Chiapas. Often they are rejected by the community, a dynamic that discourages their return, or that encourages relocation to municipal seats or peripheral neighborhoods of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. The rumors that, during their migration, they had relations with other men cause them to be rejected and stigmatized.

Central American migration to the U.S.

Though it is difficult to find reliable data regarding the passage of migrants through Mexico, Amnesty International claims that organized crime groups routinely assault, rob, extort, rape, kidnap, and murder Central Americans en route to the United States. According to the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), approximately 20,000 migrants are kidnapped each year. In the words of the special rapporteur of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) on migration, the tragedies suffered by the undocumented migrants passing through Mexico “are no less than that of the Ayotzinapa tragedy.” In light of this situation, in July 2014, the Mexican State implemented the Southern Border Program, supposedly to guarantee security for migrants. In practice, it is yet another attempt to halt migratory flows toward the U.S. This program, which makes passage through Mexico more difficult, has led migrants to seek out more dangerous means of transit, thus increasing their vulnerability to organized crime. This situation of vulnerability is even worse for female migrants.

Sexual violence against female migrants

Central American female migrants who in their places of origin suffer violence see their vulnerability increase while transiting through a country that itself is ruled by patriarchal customs and that discriminates against them for being female, migrant, and undocumented. The results include forcible sexwork for female migrants; trafficking of persons for sexual or labor exploitation; rape and sexual abuse; and physical, sexual, or psychological violence as exercised by partners, relatives, guides, and authorities, among others. According to an Amnesty International report from 2010, at least six out of every ten female migrants, including children, suffer sexual violence during their migration.

This type of violence can have grave consequences for victims, such as exposure to sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, undesired pregnancies, unsafe abortions, or lack of obstetric medical care. According to the report “Building a model of attention for migrant female victims of sexual violence in Mexico,” published by the No Borders civil organization in 2012, “women who travel in isolated places or on the top of trains run great risks of suffering sexual violence at the hands of organized crime, common criminals, other migrants, or even judicial and migratory authorities. Sexual violence is part of the terror that migrants and their families suffer, and it is, it would seem, included as part of the ‘cost’ that is demanded of migrants to arrive to their destinations. Sexual violence is so prevalent that human traffickers often see it necessary to force women to have a contraceptive injection before traveling, to prevent the possibility of pregnancy due to rape.”

The No Borders report adds furthermore that “sexual violence is also a normalized social problem that is worsened by a deficient State response in terms of the prevention, protection, and attention to the human rights of victims […]. In the case of women who decide to denounce their aggressors, there are problems in the investigation, processing, and punishment of cases of sexual violence. Though Mexico has established mechanisms for detection, attention, and prevention, these are not applied in the case of female migrants. Likewise, the absence of mechanisms for the protection of victims and the presence of patriarchal social norms that humiliate them and demand physical evidence as prerequisites to undertaking an investigation make difficult the option to present a complaint to the public authorities.” Lastly, many female migrants decide not to denounce the violence they have faced precisely because of their being undocumented, due to the fear that they would be deported to their countries of origin.

Women in search of their relatives

Another notable aspect is the leadership that women have assumed in the search for family members who have disappeared during the attempt to cross toward the U.S. In December 2014, the Tenth Caravan of Central American Women, “Bridges of Hope,” took place. Mothers from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua went on tour, following a route that crosses 10 Mexican states. The caravan succeeded in reuniting 3 of its members with their relatives: One woman found her brother after 17 years of separation, and two mothers found their sons after having lost them for 15 and 10 years, respectively.

Though the Mexican State officially counts only 157 foreigners who have been registered as missing, civil organizations estimate that at least 70,000 migrants have disappeared in Mexico.

Women who help

Due to the lack of support from authorities regarding Central American migration, a group of women was formed in the community of Guadalupe, “La Patrona,” Veracruz state, toward the goal of helping migrants during their transit. After the regional passenger train disappeared due to the privatization of the National Railroads of Mexico, migrants saw it necessary to find alternative means to complete their crossing. So they began to ride on the freight train, known today as “The Beast.” On 14 February 1995, a group of women finishing their food shopping responded to the request of assistance from migrants on the train by throwing their shopping bags to them. Thus was born the “Patronas” activist group. “I was just dedicated to my home and the work in the countryside; I didn’t know that I could help,” observes the founder, Norma Romero. Regardless, the women felt the need to act in the face of the misery they saw. Today they prepare some 20 kilos of beans and rice daily for the migrants riding on “The Beast,” serving this to them as the train passes through their communities en route north.

In the celebration of 20 years of their work, persons such as Raúl Vera López, the bishop of the Saltillo diocese; Alejandro Solalinde, from the “Brothers on the Path” migrant home in Oaxaca; and Fray Tomás González, from the “72” Migrant Home in Tenosique, Tabasco, were in attendance. Those at the event strongly repudiated the Southern Border Program, which was characterized as an attempt at “ethnic cleansing,” as it is a series of measures that does not recognize the human rights of migrants, and actually aggravates the conditions in which they travel. Raúl Vera López observed that “the women of the La Patrona community contradict the selfishness, arrogance, and greed among the politicians and authorities that have sown chaos, such that the people must move to survive.”

All these fates of women affected by migration point to a common motive: the search for a better life, whether these be women who remain and confront economic difficulties or social pressures amidst which they must empower themselves, or whether these be women who decide to leave their lands to seek out a freer life of greater self-determination in an unknown place. The journey they undertake is difficult, and it has special dangers for female migrants, such that it is important for them to find mutual aid on their journeys. In this sense, the activism of “Las Patronas” is an exemplary and emancipatory example in confronting failed migratory policies that seek to control the movement of peoples. Despite all the risks, the motor of change continues to be stronger than fear, as a migrant woman’s testimony shows: “We decided to go in order to accomplish something in life, and to provide better lives for our children.”