SIPAZ Activities (November 2006 – February 2007)

30/03/2007

ANALYSIS: Chiapas – a reactivation of a state of social conflict

31/10/2007“Without the loyalty of the armed forces, the struggle to maintain liberty, democracy, justice, law and order would be erratic and impassable.“

General Guillermo Galvàn Galvàn, Mexican Defense Secretary

Militarization in Latin America: General tendencies

The process of militarization in Mexico can be framed in a historical process that has affected all of Latin America. During the Cold War, militarization was implemented (promoted and supported by the United States and its political, economic, and commercial interests) as a defense against the “danger of communism” associated with the region and the revolutionary guerrilla movements that had emerged at that time. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the “war against drugs” and the more recent “war against terrorism” have served as justifications for using armed forces in matters of internal security unrelated to defense against external forces.

In the last years, various countries, and especially Colombia, have received economic and military support from the United States under the guise of the struggle against narco-traffic. Plan Colombia(1), implemented in 1999, has transferred hundreds of millions of dollars annually with a majority (82%) destined for Colombian military forces. Plan Colombia has been criticized for strengthening indirectly paramilitary groups, provoking violations against human rights, and contributing to aerial crop fumigations that have serious affects on the health of the area’s population and the natural environment. Recently, other projects proposed by Presidents Calderón and Bush to increase aid from the United States to Mexico in the form of military technology and advice (up to 1,000 millions of dollars according to El Universal(2)), prompting some to talk of a “Plan Mexico.” The ambassador to Colombia in Mexico has affirmed that Mexico is experiencing a “good colombianization” because there is a “very strong response” on the part of the state to combat crime(3).

Today, many denounce the implementation of neo-liberal policies that continue to require growing militarization in Latin America. Due to the interest of transnational corporations to control resources (energy resources and increasingly those related to biodiversity), locate cheaper labor forces, and expand markets, the pressure to militarize continues to be felt by Latin American governments. In this way a favorable foreign environment is created for investors, but is dangerous in respect to human rights, and in particular, to indigenous communities and opposition groups.

The New Phase of Militarization in Mexico

The growing mobilization of the army in the fight against narco-traffic (30,000 active soldiers in over a dozen states(4)), announced by President Calderòn at the beginning of his mandate as one of the “star” measures to guarantee security, is already in motion. Despite the fact that the policy was originally initiated in the 90’s by President Zedillo, the increased presence of the military under Calderón in functions of public security is noticeable. Military vehicles and uniforms already form part of the landscape around the country, and it is virtually impossible to drive hours on the road without coming across a military checkpoint.

Justification by the Federal Government

The magnitude of influence and power of narco-traffickers is one of the most urgent problems facing the country, especially the enormous amount of violence it provokes. More than one thousand persons have been assassinated only in the first 5 months of 2007(5). Up against a police force largely under orders of narco-traffickers (50% according to specialist reporter Ricardo Ravel), the federal government has opted to use each time more military forces to combat drug-related crime. The federal government also argues that the use of the armed forces is ideal due to the inferior technology and armaments the police forces have which are not adequate against narco-traffickers.

Criticisms: Unconstitutional and ineffective

Criticisms have been launched by diverse fronts: the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH) has called for the militaries “removal from the streets and that they fulfill their function (constitutional) to defend national sovereignty, not the persecution of delinquency.”

In addition to its unconstitutionality, other arguments have been presented against the use of the military to combat crime: scarce effectiveness, the exposure of armed forces to corruption that has endemically affected police and the scant preparation of the military to deal with a civilian population, which often leads to abuse of authority and episodes of violence. In the words of the CNDH: “The military is not prepared to carry out public security functions, this has to be the responsibility of the police…there are human rights violations and no respect for the law.”

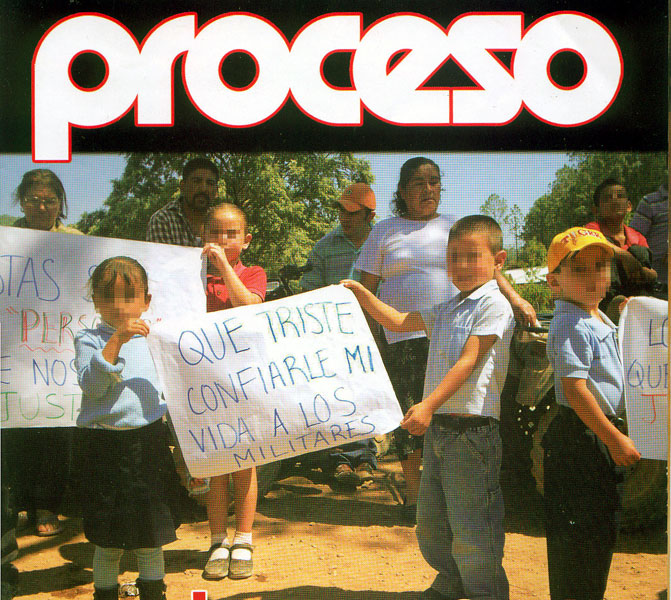

At the same time, diverse opposition forces interpret the mobilization of the military to be for the purpose of criminalizing and repressing social protest, predicted to increase as a result of popular opposition to structural reforms proposed by the federal government(6).

The Miguel Agustìn Pro Juàrez Center for Human Rights has summed up the last six months, stating, “Violence continues to grow all over the country, the flow of drugs at the border between the United States and Mexico increases continually and military personnel have committed a series of grave human rights violations(7).

Homicides and Violations: Paradigmatic cases

In the last months, Mexico has lived through extremely serious cases of violence against civilians on the part of armed forces. The victims are from society’s most vulnerable sectors: the poor, indigenous, and in particular women. According to information corroborated by Amnesty International, in February, a 72 year old Nahua indigenous woman was repeatedly raped, beaten, and tortured by various soldiers in that state of Veracruz, and later died as a consequence of the injuries sustained. In spite of the autopsy’s confirmation of the violations suffered and that her last words were “the military men got on top of me”, the government’s thesis, maintained by President Calderòn and the Ombudsman for the National Commission on Human Rights, Josè Luis Soberanes, is that the elderly woman died of gastric ulcers. Amnesty International has conveyed its fears(8) that the investigation over the incidence remains in the hands of military authorities, making it difficult to have an impartial judicial proceeding, and because the community of Ernestina, as well as witnesses, may suffer intimidation on the part of the military. Members of the community have demanded the removal of the military from the zone.

In May, four minors were sexually assaulted by soldiers of the Mexican military in the state of Michoacàn. The four girls all worked in a restaurant whose owner was being investigated by the military for her alleged ties with narco-traffickers. The military men arrived dressed in black and in camouflage. After interrogating the girls, they were tied, beaten, and lifted into a helicopter. During the flight the girls were insulted, assaulted, and threatened with being thrown overboard. In spite of asking, they were denied water to drink: “oh, you are thirsty. Let’s see, why don’t you give me some wet ones so that it’ll go away.” Once they arrived at the holding cell they were sedated. Upon waking up they continued to be interrogated, sexually assaulted, and tortured. Before they were released they were warned that if they denounced what had taken place, their families would pay the consequences. The CNDH has recognized the incidence and has called for the responsible parties to explain.

On the 1st of June, two women and three minors under the age of 8 were killed in the state of Sinaloa. They were traveling in a pick-up truck that received the impact of 24 gunshots fired by soldiers. The official version recounts that soldiers began to fire because the driver of the vehicle did not obey the order to stop. Others claim that the gunshots were fired in the dark and without warning. The president of the State Commission on Human Rights of Sinaloa affirms that “it was homicide…they shot at them before they reached [the check point](9). The driver affirmed that once they gathered the injured, three different military convoys held them up. It took 9 hours to get to the hospital, when the trip normally only takes 5 hours. It appears that medical assistance in time could have saved their lives. The military has detained 19 soldiers who will be judged by a military tribunal.

Military Court: “de facto impunity”

“No one may be tried by private laws or special tribunals. No person or corporate body shall have privileges or enjoy emoluments other than those given in compensation for public services and which are set by law. Military jurisdiction shall be recognized for the trial of crimes against and violation of military discipline, but the military tribunals shall in no case have jurisdiction over persons who do not belong to the army.”

-Article 13 of the Mexican Constitution

Although the Mexican Constitution limits military jurisdiction to crimes related to the violation of military discipline (rebellion, espionage, or desertion(10)), in all the above-mentioned cases, the responsible parties will be judged by military tribunals. There is no lack of criticism against this system. In 1998 the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture issued a report on Mexico, in which he affirmed that “military personnel appear to be immune to civil and criminal justice and generally protected by military courts.” The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) has also criticized the systematic and absolute use of military tribunals to judge military personnel: “independence and impartiality are clearly compromised (…), producing de facto impunity.” The Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights (CMDPDH) has recently indicated that military jurisdiction has negative results especially in cases of violence against women: they [the women] fear going to the military tribunals, converting themselves into “perfect victims of a dysfunctional system.”(11).

Chiapas: Militarization as counter-insurgency strategy

In 1996, SIPAZ pointed out that the government maintains about 60,000 active soldiers in Chiapas, representing a third of the country’s armed forces. Militarization of the region, in the wake of the Zapatista uprising in 1994(12), has provoked grave human rights violations including executions, torture, sexual violence, forced displacement, robberies and injuries, as well as, the deterioration of indigenous communities which must share their daily lives with armed forces(13). However, according to government declarations (2006), military presence in Chiapas is due exclusively to the needs Chiapas has as a border state, and not to the conflict with the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN). This is arguable. According to CAPISE(14) “75% of the military occupation in the state of Chiapas is located in Zapatista influenced territory.” In 2006, SIPAZ participated in a verification mission concerning circumstances in Chiapas, coordinated by the Center for Human Rights Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas. It was concluded that that the military presence in that state is not centered on the necessity to secure the border, “instead it is above all a military plan to control indigenous populations and their territory(15)“, rich in natural resources.

CAPISE documents the reaction of the assembly of communal landholders in Limar, located in the municipality of Tila in the northern region of Chiapas, to the establishment of a military base on their lands:

“Once they [military soldiers] established themselves in our territory, some of the federal military began to search private homes for women (…) they have given some kids marijuana and obligated them to have sexual relations with prostitutes at the Base of Operations. (…) The selling of alcohol does not exist in the community, but since the Base of Operations was installed, it has spread. In the parcels of some landholders, military have entered without permission to cut wood. (…) Shots from fire were heard on the 13th and 17th of May of this year and the 27th of November, and this has scared the kids and the women.”

One of the most well-know cases of violence that made it to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (CIDH)(16), took place in 1994. A group of military soldiers detained the sisters, Ana, Beatriz, and Celia González Pérez (20, 18, and 16 years respectively) and their mother Delia Pérez de González to interrogate them over their alleged membership with the EZLN. The three sisters were beaten and raped repeatedly while the other soldiers watched.

“I felt a lot of pain, feeling like I was going to die and then I don’t know what happened, when I came to I saw another soldier on top of me and I tried to scream. While they were on top of us they laughed and they said things like: “how delicious the Zapatista women are”, and “good that we took advantage of them.” I remember that my sisters screamed a lot, they didn’t say anything in particular, just screamed, crying out sometimes: “let us go”.

Before they let them go, they threatened to kill them if they denounced what had happened. Consequently, pressure from their own community that suspected misconduct on the part of the sisters, forced them to leave their home and “flee their community out of fear, shame, and humiliation.”(17). The government alleged that the case had been shelved because the sisters refused to appear in front of the military tribunal to present their testimony and submit themselves to a new gynecological exam(18) (the first exams already corroborated the acts of violence). As a result, the Mexican government sustained that there were no human rights violations that it could be charged of. However, the CIDH considered it evident that the Mexican state had responsibility in the incident and called for them to bring those responsible to justice, as well as, compensate the victims. To date, the recommendations of the CIDH have not been fulfilled and the responsible parties are free with impunity.

It is important to recognize that denouncements against grave abuses by the military continue in Chiapas, despite the fact that there is a sense of “normalization” of the military’s presence and that the police continue to be largely occupied with the security of the state.

Public Perception

According to an opinion poll by Parametría(19), 89% of the Mexican population agrees with the use of military in combating narco-traffic, and 45% prefer police forces for securing the safety on public streets. It is worrisome to see these levels of acceptance for policies that have already led to such glaring human rights violations. In Colombia, militarization has already penetrated a broad sector of society, where 75% support a president with ties to paramilitaries; there are 4 million “informants“; and a million “voluntary collaborators” in the fight against narco-traffic(20).

Conclusion: Militarization, a danger for peace and human rights

The mobilization of the military, in operations unrelated to an exterior threat to national sovereignty, can produce counterproductive results. Paradoxically, in the attempt to establish public security, one can point to a general climate of fear and insecurity caused by the abuses committed by the armed forces. For instance in relation to the problem of narco-traffic, it is important to keep in mind that it is not only about combating organized crime, while always respecting the individual rights of citizens, but also the conditions of marginalization and the lack of opportunities that provoke the delinquent behavior that need attention. Another concern is that the mobilization of the military plays a role in the control and repression of social movements. Moreover, establishing military bases in indigenous communities that reject their presence creates tension and makes difficult their co-existence. Finally, military jurisdiction continues to be limited. Common crimes, if the basic principle of equality in front of the law is respected, should be tried through civil legal mechanisms.

Notes:

- Article on Plan Colombia in Wikipedia (Return…)

- El Universal, 06/22/2007 (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- Article from El País (Return…)

- Statistics from the National Commission on Human Rights. (Return…)

- La militarización de Calderón, published in Engerìa, a newspaper of the Energy Worker’s Front (Return…)

- Website of Centro Pro (Return…)

- Urgent Action of Amnesty Inernational (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- GONZÁLEZ OROPEZA, Manuel. El fuero militar en México: La injusticia en las fuerzas armadas (Return…)

- Article from La Jornada (Return…)

- See Castro Apreza, Inés. Quitarle el agua al pez: la guerra de baja intensidad en Chiapas (1994-1998). (Return…)

- La Ocupación Militar en Chiapas: El Dilema del Prisionero. CAPISE, 2004 (Return…)

- Center for Political Analysis and Social and Economic Research (CAPISE). (Return…)

- Bulletin of Frayba (Return…)

- Case in CIDH (Return…)

- Case in CIDH (Return…)

- Marta Figueroa, lawyer of the victims, points out that it is a common strategy: demanding a new medical exam, knowing that for a women who is a victim of violence, especially those from rural areas, to go through it again terrorizes the women. As a result, their refusal is used to stop the judicial process. (Return…)

- Results of an opinion poll done by Parametria (Return…)

- RUEDA, Danilo. Militarismo en Colombia. Lecture for the 5th PROPAZ forum. San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, June 8, 2007. (Return…)