In recent months, the situation of insecurity and violence that is lived in Mexico has led different sectors of civil society to organize itself and manifest its repudiation of governmental policy in this sense. In the following we would like to present two of the initiatives that have had the greatest influence, not only in communication media but also in the national agenda: the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity and the Caravan of migrants “Step by step to Peace.”

“No more!” is heard

“No more blood” and “We are fed up” have been the explosive exclamations with which a movement was born succeeding to have an unexpected impact at the national level in a short time. It began among others with the poet Javier Sicilia, who due to his role in the initiative has been perceived as its primary figure. The movement now known as the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity (Movement) has been able to mobilize thousands of people against the strategy of the federal government to combat organized crime. This strategy, begun in 2007, has resulted in 40,000 dead, some 10,000 disappeared, and entire communities displaced by violence. If the deaths and the disappeared cannot be attributed in their totality to the armed forces and public-security forces, it is also true that the policies of the federal government have exacerbated the security situation of the country in the view of many Mexicans.

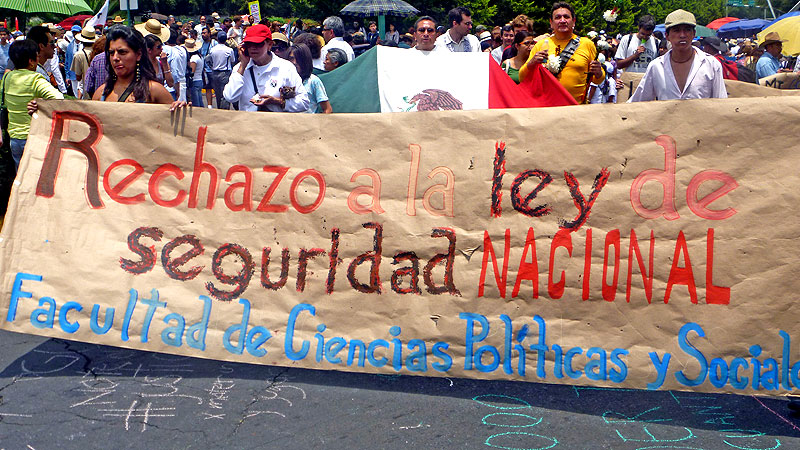

© SIPAZ

It was “one more death” (though in reality, each death is one too many) in this spiral of violence that brought about this process, firstly through mobilization and later organization. The difference about this death, in contradistinction to the others, was that the name of the deceased would soon be known by society. Juan Sicilia was the name of the youth murdered on 28 March in Cuernavaca (Morelos) together with friends of his. He was the son of the poet Javier Sicilia. Profoundly hurt and offended, Sicilia the father wrote an open letter to the politicians and to organized crime, expressing the feelings of many who are tired of so much violence and of the refusal of the federal government to change its strategy to combat organized crime. From 5 to 8 May, a walking march was held from Cuernavaca to Mexico City that ended with a massive protest in the capital’s Zócalo. On 7 May, approximately 25,000 support-bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) together with adherents to the Other Campaign and people from civil society marched in silence in San Cristóbal de Las Casas (Chiapas), in solidarity with this new movement. In its salute to the movement at the end of the march, the rebel group expressed that “today we are here because persons of noble heart and firm dignity have called on us to manifest ourselves for a stop to the war that has filled Mexico with sadness, pain, and indignation,” condemning that “tens of thousands of persons have died in this absurd war that leads nowhere.”

The next step was the Caravan for Peace with Justice and Dignity to Ciudad Juárez (Chihuahua), which is presently considered to be the most dangerous and most violent city in the world. Initiated also in Cuernavaca on 4 June, the motorized caravan crossed several states and reached the border city on 9 June. Different testimony of the events during the caravan’s journey showed that it succeeded in approaching people who have suffered the loss of a loved one but who up to then had not been politically active. In Ciudad Juárez nine work tables were held: 1. Truth and Justice from the victims; 2. End to war strategy. Citizens’ security with perspectives of Human Rights; 3. Corruption and impunity; 4. Economic roots of organized crime; 5. Alternatives for youth and measures for the reconstruction of the social fabric; 6. Participatory and representative democracy; 7. Ties and organization of the movement; 8. Labor reforms. Unemployment and economic alternatives; 9. Indigenous rights and culture, migration and alternatives in the countryside. In Juárez the “National pact for a Mexico at peace with justice and dignity.” was also signed.

It should be noted that the activities and suggestions of the Movement have been expressed non-violently. Sicilia himself in several interviews has noted that his inspiration is based in Gandhian principles of civil disobedience and nonviolent action. Pietro Ameglio, member of Service for Peace and Justice (SERPAJ) in Mexico and a person linked to the movement, explained that “The central proposal is precisely to detain this militarist ‘armed peace’ and construct together another type of peace: one ‘with justice and dignity.’ […] Many traditions have emphasized that without justice (social and legal) and dignity (in this case beginning for the victims of the war) there cannot exist peace […]. This conception of peace is not passive or violent, but rather is based on the Gandhian principle of ‘humanizing the adversary’ (knowing better the constitutional process of his identity), the Judeo-Christian idea of shalom (not to exploit the other, to redeem social and economic inequalities) and the humanist principle to ‘not do to the other what you would not have done to you.'”

Due to the magnitude of the mobilizations and the echo they have encountered, even in mass media, the federal government had to respond. On 23 June there was held a meeting in the Chapultepec Castle in which participated President Calderón and several members of his cabinet together with a number of representatives from the Movement. Though the members of the movement shared stories of pain and suffering due to their having lost loved ones, the chief executive insisted that his strategy of combating organized crime is the only option at present. At the meeting the parties agreed to a mechanism of dialogue between the movement and the government that would concentrate itself on the subjects of attention to cases of justice, the system of attention to victims, holistic revision of the national-security strategy with an emphasis on the reconstruction of the social fabric, as well as the impulse of mechanisms for participatory democracy and the democratization of the media. Following the meeting with the government, the movement held meetings with legislators in Congress and is currently seeking to meet with judges from the Supreme Court of Justice in the Nation. The Movement thus will have initiated a dialogue with the three branches of government—moves that could be considered significant advances, due especially to the short existence of the movement.

Regardless, the decisions of the Movement and the declarations of its members have also provoked critiques by analysts and those who initially had participated in the process. The first conflict within the Movement occurred after the conclusion of the Caravan to Ciudad Juárez regarding the question of whether the Army should retire immediately from public-security operations and return to its barracks or not. There are several, especially from the border city itself, who have argued that with the arrival of the Army in 2008 the number of murders and forced disappearances have increased precipitously and that for this reason the armed forces should be recalled immediately. Others have said that the replication of what for Ciudad Juárez could be a solution might exacerbate the situation in other places and with these other populations and that hence the return of soldiers to their quarters should be an incremental process.

The most controversial point to date has been the decision to hold dialogues with the government. The members of the movement who have opposed this decision claim that while the Army is deployed in the streets there are no conditions for a dialogue with the Executive. The decision in favor has been defended with the argument that such a position does not signify support for the government’s posture. In the meetings between the members of the movement with representatives of the federal government and the legislators that have occurred since August, many media have stressed that Javier Sicilia has embraced these figures, a symbolic act criticized by many. Sicilia himself has expressed his intention to “touch his heart, his conscience; this is not created only through denunciation or harsh words.” Those who defend the poet stress that it is precisely these acts that distinguish him from the political class, given that he does not seek to become a politician, much less “the” representative of organized civil society, but rather that he is firstly the father of a victim of the violence that is suffocating the country, and secondly a poet and citizen who has decided to involve himself politically with the goal of bringing about change.

In the meeting with the Legislative power, one of the principal demands of the movement was that the Congress of the Union reject the National-Security Law proposed by the president. This legislative proposal—that is, its version as of this writing—would grant the Executive the right to order the Army to provide for public security in situations that represent a “threat to national security,” without the need to consult representatives or senators at all. Upon realizing that the House of Deputies had approved the proposed reform on 3 August, the Movement decided to suspend its dialogue with the parliamentary body for having “betrayed its word” to members of the movement. The leaders of the parliamentary factions strove to clarify that what had been approved referred to the National-Security Law in general terms; they assured that there would still be a chance to change the specific points. In this way the Movement experienced the precedent that the word of its counterpart in this dialogue couldn’t be kept.

Apart from initiating dialogue with the three federal branches, the Movement has maintained its strategy of mobilizations. At the end of June, a representative of the movement visited the Purépecha community of Cherán in the state of Michoacán that since last April had had to organize the security of its people and the defense of its forests in light of the omission of the state and federal government with regard to illegal logging. The movement hopes to carry out the First National Encounter of experiences in communal security in the community of Michoacán so as to open a space for the exchange of experiences in communal defense as carried out by different social processes, above all among indigenous peoples, in light of the absence of public-security forces or governmental complicity with organized crime. Furthermore, in September there is planned a Caravan to the South, in which the Movement would come to familiarize itself with the situation of the southern states, which also shares this national situation of a “war on organized crime” and could thus present local particularities of violence and the violation of human rights.

The difficulties and challenges faced by the Movement have been and continue to be several and various. It should be noted that it was not born as an organic process but rather has united both victims and relatives of victims who had previously been unknown to each other and relatively depoliticized. It has also brought together organizations and persons with experience in social mobilizations and with a political consciousness that has been formed during years or even decades. Furthermore, it was not—and continues not to be—easy to bring together the different demands of the different groups within the movement and so construct a common agenda, given that for the victims justice is the central demand, while others prioritize the immediate exclusion of the Army from public-security operations. Furthermore, the assumption of some regarding the possibilities of generating change from within the present political system could result in the alienation of those who do not believe in this possibility, who instead champion a profound transformation of political, social, and economic structures. Regardless, to date the Movement has succeeded in attaining a certain consolidation that would allow it to continue playing a role in the definition of the national agenda.

The caravans of migrants

Another recent civil initiative that comes not only from Mexican civil society but that has a strong national presence has been the caravans of migrants. With the participation of civil organizations and relatives of Central American and Mexican migrants, until now there have been held two caravans to make visible the risks and death-threats faced by migrants in their journey to the United States in search of improving their economic situation. The first caravan, named the “Caravan Step by Step to Peace,” was held in February; in its path through Mexico it coincided with the discussion of the federal legislative branch on a law for the protection of migrants.

The second caravan, initiated on 24 July in Guatemala City, which carried the same name as the first one, was comprised of approximately 500 persons from civil organizations and relatives of migrants from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. It journeyed to the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Oaxaca, Vera Cruz, and Puebla before reaching Mexico City on 1 August. On its path it followed the route taken by Central American migrants in their journey to the U.S. via train cars and with stops in migrant houses in different states. One of the principal demands has been that for justice for the migrants who have been killed, kidnapped, or extorted in Mexican territory. Other crimes to which they have been subjected are forced disappearance and sexual aggression. The synergy of these risks allows one to see the dimension of danger experienced by migrants during their crossing of the country to reach the other side of the Río Bravo.

The alternative Report put together by members of the caravan stresses the “establishment of a legal mechanism for secure transit, whether by means of a transmigrate visa or the abolition of visas altogether.” It affirms that “eliminating the need for clandestine crossing is the only means to ensure a drastic decrease in the aggressions and violations committed against migrant populations. We cry a desperate I ACCUSE in the name of the 20,000 migrants who are kidnapped each year, people from El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Colombia, Ecuador, Cuba, and also Mexico, who have names, faces, dreams, and families that do not cease to search for them, who do not renounce the hope of finding them alive, who are not satisfied by official excuses.”

Over the course of the caravan, members were visited by the Special Rapporteur for Migrant Workers and their families from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Felipe González, who could attest to the stories of those who for various reasons see themselves as obliged to migrate. The Rapporteur qualified what he shared as “a true humanitarian tragedy.” He recognized that the new Migratory Law includes some advances, but he also made recommendations for the Mexican government with regard to the protection of migrants in their passage through Mexico.

The path taken… And the path to follow

Both initiatives presented here have succeeded in influencing the national debate, the “Step by Step” caravan in the cause of migrants, the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity in making visible the victims and social costs of the present strategy of combat against organized crime. They have demonstrated the capacity to mobilize on both questions and have furthermore respectively provided solidarity for each other. Regardless, the progress in reaching changes in governmental policy to date has been minimal, although this has less to do with civil-society mobilizations than it does with the postures of the government and its allies in Congress.

Regarding the “Step by Step” caravan, there are no further activities yet announced, and so it is difficult to predict its future path and possible impact. In contrast, the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity has a defined agenda that includes both activities within civil society, particularly the Caravan to the South, as well as the continuation of dialogue with the federal government and the parliament. It could well be the case that the arrival of the Movement to the south of the country would strengthen it and extend its focus to other local problems that also have to do with the present governmental security strategy. In any case, it remains to be seen whether the coming mobilizations will succeed in influencing the national agenda and bringing about change, or if at election-time in a year it is the candidates and electoral campaigns that completely dominate political debate in Mexico.