In Zirahuén, Michoacán, on July 14, 15, and 16, the “Second National Meeting for the Defense of Our Land and Territory and Against PROCEDE (Program of Certification of Ejido Rights and Plot Titles) and PROCECOM (Program of Certification of Communal Rights)”1 was held.

The announcement for the Meeting stated: “The implementation of programs like PROCEDE and PROCECOM, most often enacted through illegal means, with deception, manipulation, and bribery, as well as promises of public works, services, and other government programs, with many irregularities committed, denotes the existence of a policy of the State that violates current laws like the Agrarian Law, the Civil Code, the Indigenous Customary Rights, the actual Mexican Political Constitution, and a series of International Treaties, related to Human Rights, signed by the Mexican State.”

Although PROCEDE was scheduled to end in 2006, the program continues in effect. Many social and campesino organizations warn that this form of implementing such policiese likely tol continue with future governments, just with different acronyms and programs.

A Bit of History

PROCEDE was created on January 5th, 1993 with the objective of “giving juridical certainty to land ownership through the distribution of land parcel certificates and/or certificates for communal land rights, as well as land plot titles that favor the individual members of the agrarian groups that solicit and approve the programs”. This is an inter-institutional federal program that involves the collaboration of the Agrarian Reform Secretary (SRA), the Agrarian Secretary (PA), the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Information (INEGI), and the National Agrarian Registry (RAN).

In discussing PROCEDE, there are constant references to the Reform of Article 27 of the Constitution and the new Law (both issued in February 1992). To a great extent, both were part of the negotiations that led to the implementation of the North American Free trade Agreement (NAFTA), which Mexico signed with the United States and Canada in 1994.

The reforms in 1992 had various consequences for Mexican campesinos:

“a) The end of all of the land redistribution that started after the revolution of 1910 (…);

b) Lifting the legal prohibition that existed for ejido and communal lands, allowing them to now be bought, sold, rented, seized, or mortgaged and expired.

c) Permitting and promoting the ejidos and communities that possess valuable natural resources to participate in commercial sectors, associating with corporations or banks, involving their lands or forests and mountains that can now be seized or mortgaged and transferred.”2

From there comes the strong opposition of many campesino organizations to these reforms, which they consider counter-reforms and steps backwards from the achievements of the Mexican Revolution. In the early 1990s, there were many marches, sit-ins, highway blockades and occupations of government offices as attempts to have the campesino opposition heard. It is also important to note the expression of land as one of the principle demands of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) when they rose up in arms on January 1st, 1994, strategically parallel to the implementation of NAFTA on the same day.

13 Years Later

According to the report from the National Agrarian Registry, there are 27,664 ejidos and 2,278 communal land groups, totaling 29,942 agrarian groups. The ejido members and communal land holders are estimated to possess approximately 9 million parcels and plots, which covers more that half of the national territory.

Communication and sensitization efforts with the members of the ejido groups, as well as the compilation of complementary information, has allowed for the assessment of the viability of incorporating the program throughout the nation.

By the assemblies’ will, the Program has been incorporated in 96% of the nation’s agrarian groups. 91% of them have achieved, in agreement with their neighbors, the delimitation of their properties, as well as of their parcels and plots. This mediation effort has been completed in 90% of the cases. Finally, the regularization of 89% of the national total, as well as the certification and/or titling of 77.5 million hectares, has been completed.

In the face of the previously mentioned risks, it is important to note the calculation that throughout Mexico, less than 3% of all of the ejido and communal land certified in the past 13 years has come into the “Regime of Full Domain” and been totally privatized (Source 2).

There are three states that have fallen behind in the application of PROCEDE: the Federal District (in the mountains that surround Mexico City there are still ejidos and communities that cover 30,496 hectares), Oaxaca, where PROCEDE has advanced by 52%, and Chiapas, by 54% (Source 2, reflective of the end of 2005).

The Clash of Two Visions

The states with the most minimal national advance (Oaxaca & Chiapas) are in the southern part of Mexico and have a large indigenous population. In the ancestral indigenous worldview, nature is considered integral, sacred, and collective, and cannot be sold.

This idea is illustrated in this quote: “It is important to highlight the mystical element in the concept of territory. Territory is not just a piece of land, it cannot be defined in one single word (there is no direct translation in any of the primary indigenous languages of Chiapas). It has to do with where we plant our corn, where we are born, where we marry, and where we have our children. It has to do with the forest, the animals, the sacred places, the caves, the lagoons, the hills. The people are the territory. 3

This conception of land has a profound impact in the organizational forms that currently exist in a good number of the indigenous communities: “All of this, which implies seeing nature and the Earth as a mother and not as a slave, has historically been a way of working and producing in the Mesoamerican cultures. The political resistance of these cultures relies on the maintenance and strengthening of the community structures for decision-making and solidarity collaboration, as well as the preservation of the collective perception that the land and its resources are the property of everyone, of the whole community, which gives it its use and family responsibility.”4.

The indigenous vision of the land clashes with a more commercial vision: the land has been reduced, by the current economic system, to its solely material dimension, as a resource to exploit. It has been fragmented in various moments of Mexican history, under the protection of the law.

The statements made by the Agrarian Reform Secretary, Lic. Florencio Salazar Adame, on the television program Teleformula, on October 5th, 2005, can illustrate this commercial vision: “The objective of PROCEDE is, on the one hand, to avoid agrarian conflicts, and on the other hand, to incorporate those lands into the market (…) Before the reform of (Article) 27, the campesino was just the worker of the land. We need to review Zapata so that the current system of production for self-consumption transitions to production for the market.”

Criticism of PROCEDE

Many campesino and civil organizations have denounced PROCEDE and PROCECOM for the divisions they generate within communities and ejidos (some members accept the programs, while others do not). This is particularly critical in the case of Chiapas, which is already considered to have a fractured social fabric as a result of the armed conflict and the consequences of the strategy of Low-Intensity Warfare implemented to confront it.

In some cases, the decision is not made in the assemblies or abiding by the legal methods that guide this process: “If in the first assembly meeting less than 75% of the ejido members are present, the law states that a second assembly meeting must be called and that it be held one month later. This waiting period is often not respected. In the second assembly, the number of ejido members drops from 75 to 50%. At this point, an assembly act is signed by the attendees with consequences for those who do not attend. The agrarian officials justify their actions: ‘We did our work according to the decisions made by the community in accordance with the assembly’.”5

Many others question the fact that it promotes the monopolization and the sale of collective lands. “From my point of view, one part of it is ok, in finding solutions to conflicts over plot divisions. But by parceling the collective lands, whoever has money can buy and sell plots, whether they are from that community or not, and little by little they go controlling more land” (Source # 4, resident of the Northern-Selva Region of Chiapas).

Or another example: “Now, many campesinos don’t have anywhere to get their firewood, because the mountains have been parceled, and now they can’t go to the mountain because it has an owner” (Source 4, resident of the Northern-Selva Region of Chiapas).

At the Second National Meeting, one participant said: “We are all capitalists. The capital we have is the land. If we sell it to another person, it will be sold and resold until the land ends up in the hands of those that the government wants. It is just a question of time before the upper or middle class controls the land. We have very powerful enemies. They are well aware of the laws and they know how to manipulate them. The rich know all the tricks and they move forward.”

Another risk arises because the campesinos have to turn over their lands as a guarantee, and if they fail to pay back the credit, they lose their lands: “As an ejido we have organization, unity, strength; but once they individualize us, this is all weakened (…) Also, we do not know how to work these Programs. Even if I have my documents, I go to the bank and I ask for a loan, I sign my name, and at the moment that I cannot pay because I do not know how to manage the finances or the work, or I start drinking, I waste all my money and my signature ends up being the property of the bank” (Source 4, Resident of Bachajón Northern-Selva Region Chiapas). Also, when one enters PROCEDE, they are required to start paying the predial taxes not only on the plot but also on the parcel.

Irregularities have also been identified in the way that these programs are “proposed.” Theoretically: “PROCEDE has been and will continue to be, a Program of support for campesino initiative, voluntary and free, with the principle of the strict respect for the free will of the agrarian groups and the operation of it is equally sustained by the organization and active participation of the ejido members and communal landholders, which is achieved through the assemblies, where they freely decide the delimitations, destiny and allocation of their lands, in the presence of a public official and abiding by the established technical-judicial framework.” Nevertheless, there have been many reports of cases where the agents from the Agrarian Secretary visit campesinos’ homes to convince the families/heads of household to join the program.

In several cases, it has been discovered that other government programs, like PROCAMPO (Program of Direct Support to the Rural Areas) or promises of support, have been used to pressure people: “The official says that if you join the program, you will receive more assistance; he says that being united as we are, we won’t be able to find any sort of projects. And so my community believed him and that is why we joined. But the assistance we were supposed to receive never arrived; we were deceived” (Source 4).

Other critics state that the measurement of the land is incorrect. Furthermore, if they are deemed “excessive,” they are expropriated without any recognition of the time of possession and the passive use, which would give them a positive prescription (Source 4).

Finally, PROCEDE has been denounced for worsening the situation of inequality, insecurity, and discrimination of campesina women: “At first glance, the new Agrarian Code (February 1992) gives the impression of being neutral on the question of gender, as Article 12 of this law states ‘The men and women who hold ejido titles are the ejido members,’ which demonstrates the formal equality that exists in the agrarian sector. Nevertheless, this equality has not been manifested as real equality. (…) In practice this program has turned the politics of titling over to the ‘heads of household’ or simply those who are individual ejido members, once again excluding the women from access to property, in this case, to the land.”6

Organizing in Defense of the Territory

In the seminar on indigenous rights organized by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, one of the working groups concluded: “To strengthen the defense of our territory we need to organize ourselves to not fall into the traps set by the neoliberal government, and to organize ourselves as the people in resistance.”

The indigenous communities certainly have decades, or rather, centuries of experience in resistance. In the case of Chiapas, since the 1970s, the indigenous and campesino movements have grown and independent campesino organizations have emerged.

Another factor has been the organization of meetings: the First National Meeting Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM “One Decade After the Agrarian Reform,” held February 5th and 6th, 2003 in the community of San Felipe Ecatepec, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas; the First State Meeting Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM, held in the Ejido Petalcingo, municipality of Tila, Chiapas March 10-12th, 2006, and most recently the Second National Meeting for the Defense of Our Land and Territory and Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM, July 14th-16th, 2006, in Zirahuén, Michoacán.

At this most recent meeting, a decision was made to create a National Network in Defense of the Land and the Territory and Against PROCEDE/PROCECOM, to maintain a permanent interchange of experiences, as well as coordination and mutual support in the regional and state struggles.

The Final Declaration also proposes actions: “We decided to strengthen the community unity through the assemblies, with a territorial vision of autonomy; promoting the construction of community alternatives for the managing and sustainable use of the natural resources and for agro-ecological production based in local self-sufficiency and food security, creating regional markets that recover bartering. We will generate an intense informational campaign, at the local, national, and international level (…) We will also organize mobilizations in our states and regions, in support of legal actions to document illegal actions committed by the government in their effort to impose PROCEDE and PROCECOM.”

The call for unity was constant throughout the Meeting and it will certainly be necessary to face a process that creates the continuation of PROCEDE. The Declaration also expresses the fear that “in the next Presidential administration, regardless of who the next President is, the application of the privatization programs will increase.”

- 1– Ejidos: Each ejido member receives a parcel of land, and all decisions pertaining to the group’s land must be decided in the complete assembly of ejido members.

- – Communal Lands: The land belongs to the collective of the members of a community, and as such, the benefits of that land are distributed among everyone. (Return)

- 2 – “13 Years Later: PROCEDE… Proceeding?” Maderas del Pueblo Sureste AC & Foro Para el Desarollo Sustentable AC, February 2006. (Return)

- 3 – Annual Permanent Seminar “The Rights of the Indigenous Peoples, First Session: The Right to Territory for the Indigenous Peoples” Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, November 2005. (Return)

- 4 – “The Impact of PROCEDE on Natural Resources, Community Life, and the Social Fabric of the Indigenous Tseltal Communities of the Northern Selva Region on Chiapas,” Maderas del Pueblo Surests AC, Foro Para el Desarollo Sustentable AC, February 2006. (Return)

- 5 – YORAIL MAYA #4, Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, June 2002. (Return)

- 6 – Bulletin of the Centro de Derechos de la Mujer de Chiapas AC, April 2005. (Return)

The announcement for the Meeting stated: “The implementation of programs like PROCEDE and PROCECOM, most often enacted through illegal means, with deception, manipulation, and bribery, as well as promises of public works, services, and other government programs, with many irregularities committed, denotes the existence of a policy of the State that violates current laws like the Agrarian Law, the Civil Code, the Indigenous Customary Rights, the actual Mexican Political Constitution, and a series of International Treaties, related to Human Rights, signed by the Mexican State.”

Although PROCEDE was scheduled to end in 2006, the program continues in effect. Many social and campesino organizations warn that this form of implementing such policiese likely tol continue with future governments, just with different acronyms and programs.

A Bit of History

PROCEDE was created on January 5th, 1993 with the objective of “giving juridical certainty to land ownership through the distribution of land parcel certificates and/or certificates for communal land rights, as well as land plot titles that favor the individual members of the agrarian groups that solicit and approve the programs” (http://www.pa.gob.mx/Procede/info_procede.htm). This is an inter-institutional federal program that involves the collaboration of the Agrarian Reform Secretary (SRA), the Agrarian Secretary (PA), the National Institute of Statistics, Geography, and Information (INEGI), and the National Agrarian Registry (RAN).

In discussing PROCEDE, there are constant references to the Reform of Article 27 of the Constitution and the new Law (both issued in February 1992). To a great extent, both were part of the negotiations that led to the implementation of the North American Free trade Agreement (NAFTA), which Mexico signed with the United States and Canada in 1994.

The reforms in 1992 had various consequences for Mexican campesinos:

“a) The end of all of the land redistribution that started after the revolution of 1910 (…);

b) Lifting the legal prohibition that existed for ejido and communal lands, allowing them to now be bought, sold, rented, seized, or mortgaged and expired.

c) Permitting and promoting the ejidos and communities that possess valuable natural resources to participate in commercial sectors, associating with corporations or banks, involving their lands or forests and mountains that can now be seized or mortgaged and transferred.”2

From there comes the strong opposition of many campesino organizations to these reforms, which they consider counter-reforms and steps backwards from the achievements of the Mexican Revolution. In the early 1990s, there were many marches, sit-ins, highway blockades and occupations of government offices as attempts to have the campesino opposition heard. It is also important to note the expression of land as one of the principle demands of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) when they rose up in arms on January 1st, 1994, strategically parallel to the implementation of NAFTA on the same day.

13 Years Later

According to the report from the National Agrarian Registry (http://inet.ran.gob.mx/ran/archivos/PROCEDE/index.html), there are 27,664 ejidos and 2,278 communal land groups, totaling 29,942 agrarian groups. The ejido members and communal land holders are estimated to possess approximately 9 million parcels and plots, which covers more that half of the national territory.

Communication and sensitization efforts with the members of the ejido groups, as well as the compilation of complementary information, has allowed for the assessment of the viability of incorporating the program throughout the nation.

By the assemblies’ will, the Program has been incorporated in 96% of the nation’s agrarian groups. 91% of them have achieved, in agreement with their neighbors, the delimitation of their properties, as well as of their parcels and plots. This mediation effort has been completed in 90% of the cases. Finally, the regularization of 89% of the national total, as well as the certification and/or titling of 77.5 million hectares, has been completed.

In the face of the previously mentioned risks, it is important to note the calculation that throughout Mexico, less than 3% of all of the ejido and communal land certified in the past 13 years has come into the “Regime of Full Domain” and been totally privatized (Source 2).

There are three states that have fallen behind in the application of PROCEDE: the Federal District (in the mountains that surround Mexico City there are still ejidos and communities that cover 30,496 hectares), Oaxaca, where PROCEDE has advanced by 52%, and Chiapas, by 54% (Source 2, reflective of the end of 2005).

The Clash of Two Visions

The states with the most minimal national advance (Oaxaca & Chiapas) are in the southern part of Mexico and have a large indigenous population. In the ancestral indigenous worldview, nature is considered integral, sacred, and collective, and cannot be sold.

This idea is illustrated in this quote: “It is important to highlight the mystical element in the concept of territory. Territory is not just a piece of land, it cannot be defined in one single word (there is no direct translation in any of the primary indigenous languages of Chiapas). It has to do with where we plant our corn, where we are born, where we marry, and where we have our children. It has to do with the forest, the animals, the sacred places, the caves, the lagoons, the hills. The people are the territory. 3

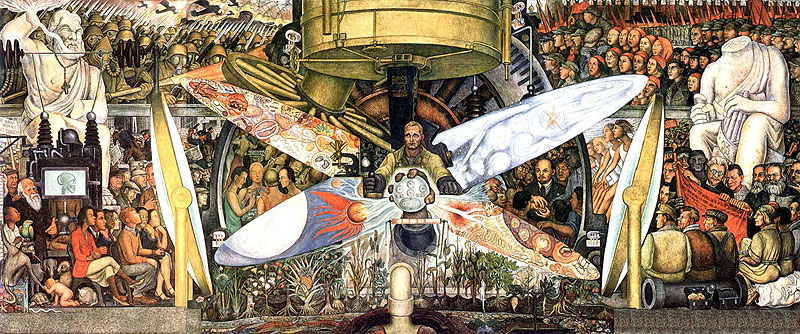

This conception of land has a profound impact in the organizational forms that currently exist in a good number of the indigenous communities: “All of this, which implies seeing nature and the Earth as a mother and not as a slave, has historically been a way of working and producing in the Mesoamerican cultures. The political resistance of these cultures relies on the maintenance and strengthening of the community structures for decision-making and solidarity collaboration, as well as the preservation of the collective perception that the land and its resources are the property of everyone, of the whole community, which gives it its use and family responsibility.”4.

The indigenous vision of the land clashes with a more commercial vision: the land has been reduced, by the current economic system, to its solely material dimension, as a resource to exploit. It has been fragmented in various moments of Mexican history, under the protection of the law.

The statements made by the Agrarian Reform Secretary, Lic. Florencio Salazar Adame, on the television program Teleformula, on October 5th, 2005, can illustrate this commercial vision: “The objective of PROCEDE is, on the one hand, to avoid agrarian conflicts, and on the other hand, to incorporate those lands into the market (…) Before the reform of (Article) 27, the campesino was just the worker of the land. We need to review Zapata so that the current system of production for self-consumption transitions to production for the market.”

Criticism of PROCEDE

Many campesino and civil organizations have denounced PROCEDE and PROCECOM for the divisions they generate within communities and ejidos (some members accept the programs, while others do not). This is particularly critical in the case of Chiapas, which is already considered to have a fractured social fabric as a result of the armed conflict and the consequences of the strategy of Low-Intensity Warfare implemented to confront it.

In some cases, the decision is not made in the assemblies or abiding by the legal methods that guide this process: “If in the first assembly meeting less than 75% of the ejido members are present, the law states that a second assembly meeting must be called and that it be held one month later. This waiting period is often not respected. In the second assembly, the number of ejido members drops from 75 to 50%. At this point, an assembly act is signed by the attendees with consequences for those who do not attend. The agrarian officials justify their actions: ‘We did our work according to the decisions made by the community in accordance with the assembly’.”5

Many others question the fact that it promotes the monopolization and the sale of collective lands. “From my point of view, one part of it is ok, in finding solutions to conflicts over plot divisions. But by parceling the collective lands, whoever has money can buy and sell plots, whether they are from that community or not, and little by little they go controlling more land” (Source # 4, resident of the Northern-Selva Region of Chiapas).

Or another example: “Now, many campesinos don’t have anywhere to get their firewood, because the mountains have been parceled, and now they can’t go to the mountain because it has an owner” (Source 4, resident of the Northern-Selva Region of Chiapas).

At the Second National Meeting, one participant said: “We are all capitalists. The capital we have is the land. If we sell it to another person, it will be sold and resold until the land ends up in the hands of those that the government wants. It is just a question of time before the upper or middle class controls the land. We have very powerful enemies. They are well aware of the laws and they know how to manipulate them. The rich know all the tricks and they move forward.”

Another risk arises because the campesinos have to turn over their lands as a guarantee, and if they fail to pay back the credit, they lose their lands: “As an ejido we have organization, unity, strength; but once they individualize us, this is all weakened (…) Also, we do not know how to work these Programs. Even if I have my documents, I go to the bank and I ask for a loan, I sign my name, and at the moment that I cannot pay because I do not know how to manage the finances or the work, or I start drinking, I waste all my money and my signature ends up being the property of the bank” (Source 4, Resident of Bachajón Northern-Selva Region Chiapas). Also, when one enters PROCEDE, they are required to start paying the predial taxes not only on the plot but also on the parcel.

Irregularities have also been identified in the way that these programs are “proposed.” Theoretically: “PROCEDE has been and will continue to be, a Program of support for campesino initiative, voluntary and free, with the principle of the strict respect for the free will of the agrarian groups and the operation of it is equally sustained by the organization and active participation of the ejido members and communal landholders, which is achieved through the assemblies, where they freely decide the delimitations, destiny and allocation of their lands, in the presence of a public official and abiding by the established technical-judicial framework.” Nevertheless, there have been many reports of cases where the agents from the Agrarian Secretary visit campesinos’ homes to convince the families/heads of household to join the program.

In several cases, it has been discovered that other government programs, like PROCAMPO (Program of Direct Support to the Rural Areas) or promises of support, have been used to pressure people: “The official says that if you join the program, you will receive more assistance; he says that being united as we are, we won’t be able to find any sort of projects. And so my community believed him and that is why we joined. But the assistance we were supposed to receive never arrived; we were deceived” (Source 4).

Other critics state that the measurement of the land is incorrect. Furthermore, if they are deemed “excessive,” they are expropriated without any recognition of the time of possession and the passive use, which would give them a positive prescription (Source 4).

Finally, PROCEDE has been denounced for worsening the situation of inequality, insecurity, and discrimination of campesina women: “At first glance, the new Agrarian Code (February 1992) gives the impression of being neutral on the question of gender, as Article 12 of this law states ‘The men and women who hold ejido titles are the ejido members,’ which demonstrates the formal equality that exists in the agrarian sector. Nevertheless, this equality has not been manifested as real equality. (…) In practice this program has turned the politics of titling over to the ‘heads of household’ or simply those who are individual ejido members, once again excluding the women from access to property, in this case, to the land.”6

Organizing in Defense of the Territory

In the seminar on indigenous rights organized by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, one of the working groups concluded: “To strengthen the defense of our territory we need to organize ourselves to not fall into the traps set by the neoliberal government, and to organize ourselves as the people in resistance.”

The indigenous communities certainly have decades, or rather, centuries of experience in resistance. In the case of Chiapas, since the 1970s, the indigenous and campesino movements have grown and independent campesino organizations have emerged.

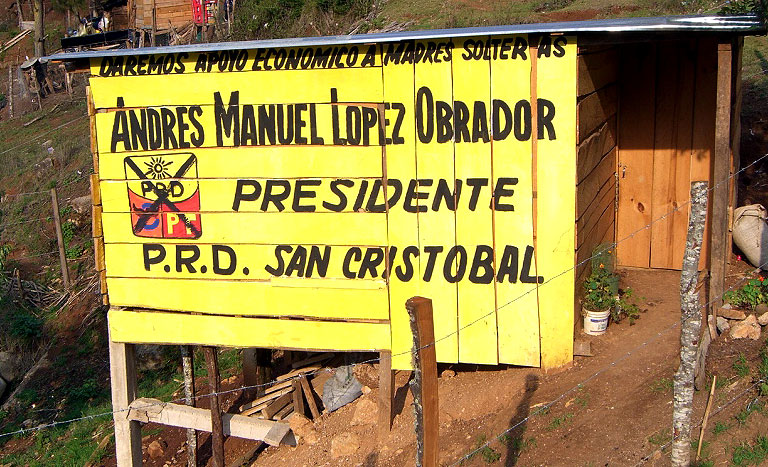

Another factor has been the organization of meetings: the First National Meeting Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM “One Decade After the Agrarian Reform,” held February 5th and 6th, 2003 in the community of San Felipe Ecatepec, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas; the First State Meeting Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM, held in the Ejido Petalcingo, municipality of Tila, Chiapas March 10-12th, 2006, and most recently the Second National Meeting for the Defense of Our Land and Territory and Against PROCEDE and PROCECOM, July 14th-16th, 2006, in Zirahuén, Michoacán.

At this most recent meeting, a decision was made to create a National Network in Defense of the Land and the Territory and Against PROCEDE/PROCECOM, to maintain a permanent interchange of experiences, as well as coordination and mutual support in the regional and state struggles.

The Final Declaration also proposes actions: “We decided to strengthen the community unity through the assemblies, with a territorial vision of autonomy; promoting the construction of community alternatives for the managing and sustainable use of the natural resources and for agro-ecological production based in local self-sufficiency and food security, creating regional markets that recover bartering. We will generate an intense informational campaign, at the local, national, and international level (…) We will also organize mobilizations in our states and regions, in support of legal actions to document illegal actions committed by the government in their effort to impose PROCEDE and PROCECOM.”

The call for unity was constant throughout the Meeting and it will certainly be necessary to face a process that creates the continuation of PROCEDE. The Declaration also expresses the fear that “in the next Presidential administration, regardless of who the next President is, the application of the privatization programs will increase.” 1- Ejidos: Each ejido member receives a parcel of land, and all decisions pertaining to the group’s land must be decided in the complete assembly of ejido members.

– Communal Lands: The land belongs to the collective of the members of a community, and as such, the benefits of that land are distributed among everyone. (volver)

2 – “13 Years Later: PROCEDE… Proceeding?” Maderas del Pueblo Sureste AC & Foro Para el Desarollo Sustentable AC, February 2006. (volver)

3 – Annual Permanent Seminar “The Rights of the Indigenous Peoples, First Session: The Right to Territory for the Indigenous Peoples” Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, November 2005. (volver)

4 – “The Impact of PROCEDE on Natural Resources, Community Life, and the Social Fabric of the Indigenous Tseltal Communities of the Northern Selva Region on Chiapas,” Maderas del Pueblo Surests AC, Foro Para el Desarollo Sustentable AC, February 2006. (volver)

5 – YORAIL MAYA #4, Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, June 2002. (volver)

6 – Bulletin of the Centro de Derechos de la Mujer de Chiapas AC, April 2005. (volver)