SIPAZ Activities (From mid-November 2010 to mid-February 2011)

28/02/2011

ANALYSIS: Current Events: Seeking alternatives to increasing militarization

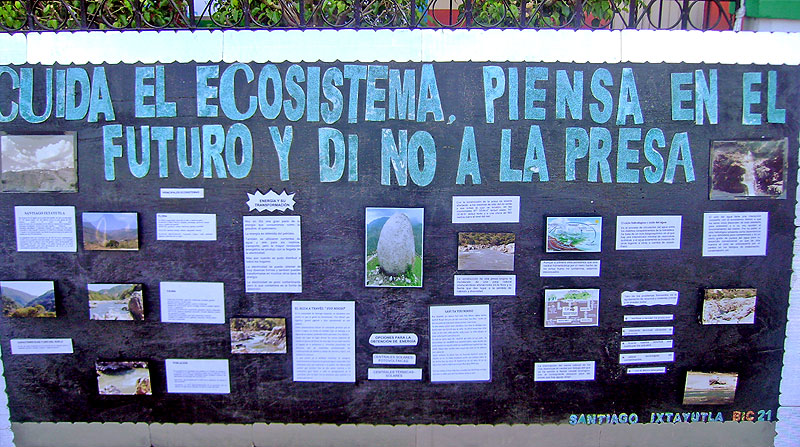

31/08/2011For the past 14 years, March 14 is celebrated globally as the International Day of Action against Dams. This year in Mexico several activities and marches were organized in different parts of the country, including Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero. Calculations made by the Inter-American Association for the Defense of the Environment indicate that, up to the year 2000, more than 170,000 people had been registered as displaced by the construction of 20 of the more than 4000 projects under consideration. Since 2006, the Mexican government announced there would be a significant increase in the generation of hydroelectric, wind, and geothermal energy between 2005 and 2014. Presently, 21% of the electricity produced in Mexico comes from hydroelectric resources: it is thus the second-greatest source of energy in the country. With the idea to expand hydroelectricity’s contributions in mind, new projects could be implemented, although some of these have already been met with rejection and organizational processes that hope to prevent the realization of such projects.

Two myths with regard to dams

There exist at least two myths regarding dams: one is to consider them as symbols of economic development. In the 1980’s, Mexico was the country with the highest number of population displaced by hydraulic and hydroelectric projects at the global level, the fruit of a strategy that focused a great deal of its efforts on the construction of large infrastructural projects. This perception has been maintained to date by some actors.

In a more recent example, Manuel Añorve, mayor of Acapulco and ex-candidate for the governorship of Guerrero, reiterated his support for the construction of the La Parota hydroelectric dam, arguing that “no one can be opposed to the development of Acapulco.” He affirmed that the dam is “a new and important project ecoomically that would generate 10,000 jobs.”

“Industrial development” and the largest processes of economic integration cannot be conceived without electrical energy as one of its motors. In the design and implementation of Plan Puebla Panamá (renamed now Plan Mesoamerica), large infrastructural projects (highways and electricity grids) have been considered priorities and have advanced since 2004. The implementation of the System of Electrical Interconnection for the Countries of Central America (SIEPAC), which would promote electrical connections between Guatemala and Mexico and Panama and Colombia, is now imminent.

However, not only activists and organizational processes against dams have questioned this model of “development.” In a report published in 2009, the Global Commission of Dams (an organization paradoxically backed by the World Bank, the financial institution that historically has promoted these types of mega-projects) recognized that “in too many cases, to obtain these benefits there have been unacceptable and often unnecessary costs, especially in social and environmental terms […]. In comparison with other alternatives, the lack of equity in distribution of benefits has brought into question the value of dams in relation to the satisfaction of the necessities of water and energy for development.”

The second myth regarding dams is to consider hydroelecricity as “green energy” or non-polluting in its manner of production and use. This perception can make dams appear particularly attractive in light of the fact that the worsening of the “greenhouse effect” and the consequent global warming have resulted in the construction of an international consciousness regarding these problems. Hydraulic energy is obtained through exploitation of the energy of water-currents. Certainly, one of its principal advantages is that it is a form of renewable energy that does not produce smoke or chemically pollute the water. This notwithstanding, it would be considered “green energy” only if its environmental impact were to be minimal and if the force of water could be used without damming it, which is not the case with hydroelectric dams. The Global Commission on Dams has affirmed as well that “the generalized impacts of large dams have exacerbated conflicts having to do with the location and impacts of large dams, both those that exist and those planned to be built. This has all made large dams one of the most controversial questions in sustainable development.”

The basis for resistance: principal challenges to dams

In general terms, the construction of dams can result in the violation of a number of human rights recognized by Mexico and internationally. In the case of indigenous populations these rights are stipulated in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization and more recently in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, both of which are recognized by the Mexican State.

Obviously, the primary victims in these projects are those who find themselves expelled from their place of residence so as to make possible the construction of dams. It is estimated that the 45,000 large dams built to date in the world have displaced 80 million people from their lands and dwellings. In the case of Mexico, the federal government by law has the right to expel parts of the population from their lands to implement projects considered to be of “public interest.” Nonetheless, those to be expelled would have to be informed, consulted, and compensated.

According to the organization International Rivers, “More than 575 large dams have been built on the rivers of Mexico. The country is home to the tallest dam on the American continent and the sixth largest in the world: the Chicoasén Dam in the state of Chiapas. The dams in Mexico have displaced more than 167,000 persons. The Timescale Dam in Oaxaca displaced nearly 25,000 indigenous Mastics […]. The majority of the displaced received no compensation for their lands and other lost possessions, and when they protested their homes were burned down. The promises for electricity and irrigation were never observed, and nearly 200 displaced people died.”

Gustavo Castro Soto from Otros Mundos Chiapas details that “[t] o build a dam there are generally seven basic elements promised to those who are to be displaced: electrical energy in the new area to be resettled; potable water, sometimes free; food; ‘development’ project; paved roads; transport; and the construction of social infrastructure such as health clinics and schools. They are always promises that go unobserved, and on occasions 5, 25, or even 50 years have passed during which the dam is utilized, and the affected population never sees the promised benefits.”

In the analyses made of impacts, many times those who do not have land or legal title to such, or those who work for landowners, are not considered, and these are not isolated cases in the complex reality of the Mexican countryside. This means that such people can be overlooked by the consultation processes as well as by compensation-schemes (when they exist). In the case of La Parota in Guerrero, the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights mentions the example of the agrarian center of Cacahuatepec in which reside more than 40,000 persons, while its owner (padrón) recognizes only 7,286 persons as comuneros there.

Far from being a source of green energy, dams have strong negative environmental impacts: they constitute one of the principal causes for the loss of millions of hectares of forests, many of which are abandoned below the water and in state of decomposition. While it is true that dams do not emit smoke, they do release large volumes of carbon-dioxide and methane, the two most problematic greenhouse-gases. Dammed rivers also carry within them more organic sediment to the dam itself, increasing the amount of organic material in decomposition. Additionally, the stagnant waters found behind dams can generate a multiplicity of diseases of both major and minor seriousness, including gastrointestinal conditions, plagues, and mosquito-based afflictions.

Dams also result in serious losses for biodiversity. Terrestrial fauna is displaced to areas far-removed from the dam that are not always adequate for their survival, and they are forced to compete with populations that already exist in such, or even die by drowning. According to Gustavo Castro, “The discharge of cold water from dams kills some species of fish and all the biodiversity that depends on natural flooding. Dams displace and kill animals and eliminate wetlands, aquifers, and unique forests as well as make lands less fertile because of the natural sediments no longer carried by rivers. The opening of paths to make possible the passage of machines and other infrastructures, requires that more trees be deforested. In addition, the displaced destroy more forests when they resettle, thus further eliminating biodiversity. Reforestation plans in other places so as to mitigate the impacts of dams are not considered either.”

In terms of environmental impact, it is relevant to mention that large dams affect seismic effects due to the pressure exercised by the accumulation of large quantities of water behind dams. In the case of Mexico, several dams have been built in areas known for earthquakes.

It is also stressed that the average increase of costs of large dams is 56% more than is initially calculated, thus generating indebtedness of governments and peoples, but in general it is considered that these increases are due largely to acts of corruption. Lastly, in more than one case, planned dams are advanced by means of repression, disinformation, trickery, and outright militarization. The Global Commission of Dams concludes that “The economic profitability of large dams continues to be difficult to establish, given that the social and environmental costars are not sufficiently considered in economic terms. More concretely, with the ignoring of such impacts and the failure to observe the required commitments, there has resulted the impoverishment and suffering of millions of persons, giving rise to an increased opposition to dams among those affected by such the world over.”

Three examples in southeastern Mexico

CHIAPAS

Presently, Chiapas has the largest hydroelectric system in Mexico, with 50% of the hydroelectric generation that is equivalent to 3% of aggregate electricity. In the case of Chiapas, beyond the projects under construction, there would have to be highlighted the risks involved in the case of a number of dams that are already operating; it should be noted that dams can be utilized for approximately 50 years. During times of heavy rainfall (a meteorological phenomenon that has worsened in recent years), dams and the surrounding population can find themselves threatened due to the possibility that the dam’s wall will be broken or chipped or even by the decision to release a given amount of the trapped water so as to mitigate this first threat. In any case, dams can add to the problems of flooding.

In November 2007, a landslide of 500,000 tons of debris entirely destroyed the community of Juan Grijalva, interrupting the flow of the Grijalva River and suspending the operation of the hydroelectric system. The affected population was relocated in “Nuevo San Juan Grijalva,” the first Rural Sustainable City, an option strongly promoted by the state but questioned by civil-society actors. To limit risks for the future, tunnels were constructed between 2009 and 2011 in the curves of the river in light of the possibility of extraordinary rains.

In 2010, Humberto Marengo Mogollín, coordinator of Hydroelectric Projects of the Federal Commission on Electricity (CFE), declared that 33 adequate sites exist for dams and that there is potential for more within Chiapas. In March of this year, the VIII Meeting of the Mexican Movement of those Affected by Dams and in Defense of Rivers (MAPDER) took place in Huitiupan, where 30 years ago an attempt was had to build the Itzantún dam that was met with the resistance of residents who succeeded in having the project cancelled in 1983. If reactivated, 11800 hectares would be lost, residents of between 30 and 35 indigenous communities would lose their lands, and dozens of communities from six neighboring municipalities that benefit from the Santa Catarina River would be affected.

OAXACA: PASO DE LA REYNA

Since 1966, the CFE has carried out a number of studies on the Río Verde—in the Sierra Sur and Coast of Oaxaca—to determine the hydrological, geological, environmental, and social characteristics found there, as well as the hydroelectric potential of this important basin in the country. Since February 2006, CFE has been visiting localities in the zone towards the end of proposing part of a project named “Hydraulic Opportunities of Multiple Uses-Paso de la Reyna.” This dam would have a wall of 195 meters and would directly affect 3100 hectares in 6 municipalities and 15 localities on the Oaxacan coast. These communities are comprised of indigenous Mixtec and Chatina populations as well as by mestizos and Afro-mestizos. The dam would impede the normal flow of water to the national park of the Chacahua lagoon which would affect the fragile ecosystem and the rich and unique biodiversity there – thus imperiling the survival of several animal and plant species.

The Council of Peoples United in Defense of Río Verde (COPUDEVER) was founded on 9 June 2007 in San José del Progeso Tututepec to defend territory, water, and other natural resources. The opposition to the construction of the dam has been increasing in the zone, abd the Council is denouncing that their word has been ignored, especially in light of the risks such a project would mean for current residents.

GUERRERO: LA PAROTA

The La Parota project has been a work in progress for more than 30 years. A series of studies were made between 1976 and 2002. In 2003, the CFE brought its heavy machinery to built the roads that would be needed to build the dam, a process that has to date been halted.

According to the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights, construction of the dam would affect 21 communities. It would inundate 17300 hectares of fertile and productive lands. 25,000 people would be directly displaced because their lands would be flooded (although the CFE recognizes only 3,000 who it says would be affected). Indirectly, some 75,000 persons would be affected by the deviation of the river. Without water to irrigate their lands and hence live, campesinos in question would have nothing on which to subsist (the CFE does not anticipate compensating those who would be indirectly affected).

Tlachinollan has denounced the strategy of imposition in the “disingenuous offer of productive works, services, and projects that have divided families and communities, thus tearing apart the social fabric. The lack of information and consultation to those who would be affected by the project violates their fundamental rights. The call for and realization of communal assemblies have violated the Agrarian Law and the state of right. The disproportionate employment of public-security bodies to monitor the assemblies in question [is also a rights-violation, as is] the criminalization of those who oppose the project by means of the release of arrest-orders on charges for which evidence is lacking and the death-threats received by some of the opponents to the project.” The divisions have resulted in three deaths, three grave injuries, four detained and seven imprisoned, to say nothing of the multiple injuries resulting from confrontations that have occurred in assemblies.

In 2003, campesinos of the region who would be affected by La Parota founded the Council of Elides and Communities Opposed to La Parota (CECOP). They have succeeded in canceling the contracting-out by the CFE to private firms for the construction of the dam as in impeding that the Mexican government release an expropriation decree. CECOP has been aided in particular by international support, including several UN rapporteurs as well as the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. Juridically, CECOP have won five cases annulling “fixed” assemblies that ‘approved‘ expropriation. Ángel Aguirre, the new governor, has affirmed that he will respect the decision of the comuneros but in a meeting with CECOP on 7 May rejected the call to sign a document called the Cacahuatepec Accords, which reject the hydroelectric project. CECOP says that it will continue struggling until it sees a resolution against construction of the dam in the Official Diary of the Federation.

Local impact, global struggle

While it is true that the impacts of the construction of dams are principally but not exclusively felt at the local level. But also part of the strength of oppositional movements can be found in creating the capacity to construct networks, both national and international. It is important to recognize that the electrical energy from which some of us benefit has often resulted in tragedy for millions of humans and other living beings, the inundation of millions of acres of potentially fertile lands, and the climatic impacts we all suffer today.