ANALYSIS: Mexico 2008, Turbulence on the horizon?

29/02/2008

ANALYSIS: Mexico – Increase in cost of living and poverty pose major concerns

29/08/2008“Some indigenous peoples have risen up in arms [Chiapas, 1994]. We have done nothing but raise our voices and still the government considers it a crime.” –Xochistlahuaca, Guerrero

According to the socioeconomic indicators of the National Population Council (CONAPO, Consejo Nacional de Población), Chiapas, Oaxaca and Guerrero delineate a triangle of extreme poverty in Mexico. Unfortunately, this is not the only factor that these three states have in common: they are also characterized by discrimination, racism, impunity, militarization, and repeated human rights violations.

With this commonality as a starting point, since 2004 the International Service for Peace (SIPAZ) has extended its base of operations (initiated in Chiapas in 1995) to include the neighboring states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. In Chiapas SIPAZ has learned that international attention can decrease the level of direct violence experienced by communities or individuals in resistance. Additionally, this attention puts pressure on federal and state governments, increasing the political cost of their repressive acts, and urging them to reduce the violence of a given situation.

After many visits to Guerrero made by SIPAZ members in the last three years, the team decided to open up to others the possibility of experiencing firsthand the state’s political and social situation. Such an introduction would give individuals enough information to formulate a cogent political response. Accordingly, SIPAZ coordinated an international delegation to Guerrero between March 7 and 14, 2008. Representatives of 11 Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) from the United States, Austria, France, Sweden, Switzerland, and Latin America participated in the delegation, offering their ample experience in the fields of human rights, peace and social conflict.

Although the delegation couldn’t travel to all areas of the state, many disturbing tendencies were observed including: the persistence of serious human rights violations, as well as the risk of increasing violence in light of continuing impunity, militarization and criminalization of social protest.

Principle concern: “criminalization of social protest?”

Although the government officials SIPAZ interviewed do not recognize the validity of the term “criminalization of social protest,” it was repeatedly mentioned by social organizations in their interviews and meetings with the delegation. Moreover, they spoke of threats, detentions (including mass arrests both during and after demonstrations), and arrest warrants or legal proceedings against their leaders. In La Parota, for example, testimonies of this sort are common: “Some of our compañeros were in jail. We were defending what is ours, our human rights. That has been our great crime.”

A representative of the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa told SIPAZ, “On November 14, we were defending our rights in a sit-in in front of Congress, when we were forcibly removed. We were supposed to have met with the deputies but they sent in repressive forces. […] On November 30, they engaged in a second repressive act. We were in the tollbooth, handing out flyers on the issues we have raised, and again they sent in repressive forces. We withdrew from the booth and at the same time they advanced on us. They grabbed us, hit us and took us to the attorney general. They arrested us for making attacks on the highway, disturbing the peace and robbery.”

One member of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Guerrero (APPG, Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Guerrero), described the framework of these repressive acts: “One of the precedents is the fact that Lucio Cabañas [leader of a former guerrilla group in Guerrero] attended this school. Before the repression, the Secretary of Education had already linked the students of Ayotzinapa with guerrilla groups. That was a very controversial declaration. From that point on, the surveillance and repression has been constant. They issued arrest warrants for us. In fact, almost all of the social activists in Guerrero have a warrant out for their arrest: for rioting, sabotage, attacks on the highways or sedition, as if they were terrorists.”

The president of the Guerrero State Human Rights Commission (CODDEHUM Comisión de Defensa de los Derechos Humanos), Juan Alarcón Hernández, pointed out that “They refer to human rights defenders as criminals. As per the constitution and international conventions, everyone is innocent until proven otherwise. The government engages in repressive acts to intimidate the people and put an end to social movements. However, civil organizations continue to protest and hold demonstrations. [The state’s response] has been excessive and has not proven effective.”

The Secretary of Government, Armando Chavarría, emphasized, “We are a democratic government, stemming from the popular will of the people of Guerrero, […] and we have tried to conduct ourselves with respect towards the citizenry. The problem is that in a context of struggle the rights of third parties are violated. We find ourselves at a crossroads, in a dilemma as to how to act. In exceptional cases, we have had to apply the letter of the law, up to the point of using security forces. I mention this so you can better understand the circumstances. We have always prioritized a policy of dialogue.”

Room for dialogue: contrasting versions

Once again, there are differing versions as to the possibilities of dialogue. The Secretary General of Government in Guerrero, in his interview with the SIPAZ delegation, affirmed, “At this same table we have carried out hundreds of meetings with social organizations. There is always a willingness to arrive at an agreement. We have different points of view, yes. This does not create a problem for us. We understand that the people are unsatisfied.” However, the social organizations have pointed out the government’s closed attitude when presented with their demands.

Within the framework of an assembly created in the region in August 2007, an agreement was signed between the Council of Ejidos and Communities in Opposition to La Parota (CECOP, Consejo de Ejidos y Comunidades en Oposición a La Parota) and the Cahuatepec authorities in which they ratified a “no” vote to the construction of the hydroelectric dam. The next day however, the authorities chose not to ratify the agreement. According to CECOP, “Ever since then, the government refuses to recognize this assembly and acts as if it has never existed. Instead, [we] propose a new consultation with the support of the UN and the CNDH. The August assembly is legally valid, something the government refuses to accept.”

Another representative of the CECOP added, “At this stage, who is going to believe that they’ll conduct a real investigation? Those who can make the decision, the campesinos, have already done so: it’s not going to happen. Yesterday they announced that they were going to conduct an audit at the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE, Comisión Federal de Electricidad) to learn how much they had spent in their attempt to impose the dam project. They’ve built roads and handed out medicines, neither of which is part of their role. They continue to give funding, including planting trees in areas that will eventually be flooded if they build the dam. Before, there was no support for anyone. Now, all of a sudden, they want to ‘help’ us and if someone opposes them, they begin to persecute them. Many have been imprisoned, there have been two deaths. We will not allow one more death, one more imprisonment.”

Background: impunity and militarization

“Not all the rapes have been reported, because there is no guarantee that a judge will hear the case, and even less that anyone will be convicted.”

–Organization of the Me’phaa Indigenous Peoples (OPIM, Organización del Pueblo Indígena Me’phaa), Ayutla

When faced with human rights issues, the state government highlights the difficulty of proceeding without crimes being reported. The Secretary General of Government insisted, “I have asked the NGOs and the social organizations to present the corresponding reports. Until now, what we have are not reports of crimes but declarations to the media stating that violations are being committed, that there is mistreatment, that [the government displays] an inappropriate attitude. […] But I repeat that we do not have the necessary elements to act. […] Certainly there have been human rights violations. No country has escaped that. However, when the CODDEHUM or the CNDH have sent us recommendations, we have responded.”

On the other hand, several social organizations told SIPAZ of the context of impunity that has continued since the “dirty war” (during the 1960’s and 1970’s) as is the case of those forcibly disappeared. According to Abel Barrera, director of the Tlachinollan Human Rights Centre of the Montaña (CDH Tlachinollan), “since the 70’s the armed struggle brought a burden of more than 500 forcibly disappeared people across the state. It is a wound that has not been able to heal, a factor that weighs on people until today.”

This situation of impunity cannot be viewed as pertaining to the past when one considers the cases of women raped by the army in the Ayutla region (cases that were presented in 2002 and have yet to be solved). Given the continuing impunity and the discrediting of state entities implicated in the administration of justice, many victims choose not to report crimes, preferring to bring their cases before the public opinion, or report to federal or international institutions.

Another factor repeated by activists is the intense militarization, justified as part of the battle against drug trafficking. According to some social organizations, this has merely been a pretext. Abel Barrera of CDH Tlachinollan emphasized, “The Montaña of Guerrero is the country’s primary location of poppy crops. Guerrero is among the most militarized, most drug influenced, most violent and poorest states in the country. However, the government’s responses primarily demonstrate a vision of security and militarism. The violence has been normalized and continues to provide a ‘justification’ for the use of ‘state violence.’ The government is not addressing the structural causes behind the drug violence. They automatically resort to an armed response, when that is not the method that should be used in resolving this problem.”

In their final statement, the international delegation concluded that “the authorities should recognize that the solution to this serious situation lies in the creation of job opportunities that allow the people to live in a dignified manner, not militarization.”

Extreme poverty should not be an excuse

Throughout the tour of Guerrero, the delegation witnessed and heard of the extreme economic, political and social marginalization that the majority of the state finds itself in, especially in regions with a majority indigenous presence. Of particular concern are the issues of health, education, nutrition, housing and dignified employment. For example, 96% of the indigenous population of Guerrero does not have access to adequate health services, due to a lack of hospitals with qualified personnel and basic equipment. The Montaña region has one general hospital and two ambulances to attend around 400,000 people. While the delegation recognizes the challenges that poverty carries with it, it is unacceptable that the state government blame its lack of promotion and defense of human rights on this situation.

Given their poverty, many people from Guerrero consider migration the only option for survival, which in itself is not a solution. Guerrero is the number one state in terms of migration rates within Mexico, and number five in terms of international migration rates.

Many are aware of the risks involved in illegal immigration to the United States, not only in the border crossing, but also in daily life once they arrive. However, immigration continues to be strong: approximately 73,000 people from Guerrero immigrate to the United States every year. More than 950,000 people from Guerrero, both undocumented and nationalized, live on “the other side.”

The delegation heard testimonies on the inhumane conditions experienced by agricultural day laborers who leave their homes for temporary work in Mexico’s northern states. For example, in Chiepetepec, an ex-day laborer told us, “There, though it’s hard, you don’t die of hunger the way you do here. Here, if you don’t die of hunger, you’ll die of some disease because there is no money. Over there, they pay very little. They treat us badly, there are insults and mistreatment. The company does not comply with its obligations. For example, they’ll call a doctor, but there’s no medicine. […] Sometimes I sleep two hours per night, sometimes I eat once a day. It is very difficult but it is also a good thing because it helps us get out of poverty, more or less. Thank God we were able to get the money and buy land [in Chiepetepec] and build a house.”

Risks of increasing violence and construction of alternatives

In the end, given the previous experience of many delegates in Chiapas and Oaxaca, the delegation left Guerrero expressing fear that the limitations to dialogue would lead social actors to struggle through violent means. In all cases, several points were echoed: divisions, polarization and a deterioration of the social fabric. For example, in Ayutla de los Libres, the delegation received reports of paramilitary activities: “In the communities there are individuals, dressed as civilians, who want to divide the people. They’re indigenous people, too. The government seeks these divisions in order to claim that indigenous people are fighting among themselves, so they must intervene. There are many problems with paramilitary groups.”

The delegation expressed concern at the risk that power struggles and general conflict would increase in the context of elections later this year. The delegates concluded, “we do not consider the situation in Guerrero as separate from our own realities. In fact we feel in part responsible, as we consider the poverty seen here – part of a broader context of structural violence which is intensified by the neoliberal policies implemented by our countries.”

… … … … … …

Building alternatives

- At La Parota (Acapulco), the community has organized to defend their territories and natural resources. For three years they have engaged in picket lines to prevent the entrance of the Federal Electricity Commission. These actions have included a strong show of women. According to Abel Barrera, director of CDH Tlachinollan, “This movement has been an example at the national level. They have defeated the government in the courts. Behind this is a social movement that has constructed itself as a subject who defends its land. It is an example of re-indigenization in which campesinos assume their historic identity.”

- In Ayutla de los Libres (Costa-Montaña), a key part of the struggle has focused on the militarization of the region, the corruption of authorities and the discrimination and abandonment of the indigenous peoples. The Organization of the Me’phaa Indigenous Peoples (OPIM), in addition to denouncing these injustices, is constructing alternatives which will ensure dignified lives for the Me’phaa communities of the Costa-Montaña. On April 17 this year, five leaders and members of the OPIM were detained and imprisoned in response to an arrest warrant for the crime of homicide. Another 10 arrest warrants are open for members of the organization, among them the president Cuautémoc Ramírez. It is worthy of note that the OPIM has been notable in its accompaniment of Inés Fernández Ortega and valentine Rosendu Cantu, the two Me’phaa women raped by soldiers in 2002 – a case which is currently before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The OPIM also denounced the forced sterilization of 14 men in the community of Camalote in 1998. Because of these denouncements, several members of the OPIM have suffered threats and harassment.

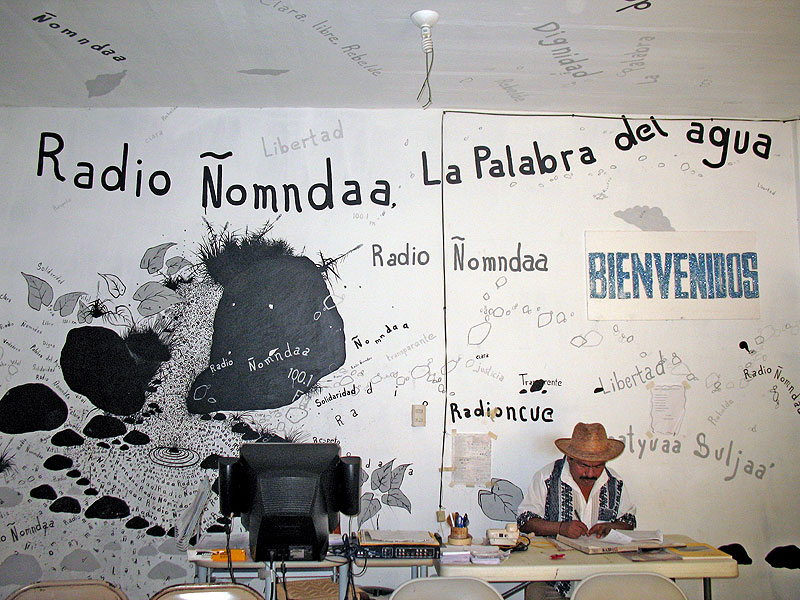

- In Xochistlahuaca (Costa Chica), the Amuzgo people have also been organizing. They have developed a structure with traditional authorities, and three years ago established a community radio station which transmits in the Amuzgo language. Xochistlahuaca’s traditional authorities and the council of Radio Ñomndaa have 11 apprehension orders open as a result of their revindication of the rights of indigenous people to maintain their own justice systems, as recognized in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization. Three of these warrants have been executed.

- Another successful experiment has been the Community Police. Communities came together in assemblies and created an integrated justice system, to be implemented by indigenous authorities. The headquarters is located in San Luis Acatlán, however there are various new branches as well. The organization is comprised of an armed entity to defend the community (the community police), and a political-legal entity to apply justice (the Regional Council of Community Authorities; CRAC, Consejo Regional de Autoridades Comunitarias). This year marks the thirteenth anniversary of the organization. Members of the CRAC and the Community Police are subject to more than 30 apprehension orders for exercising their rights.

- In the Montaña region, Abel Barrera highlights that, “300,000 indigenous people live there, the poorest of the poor (including two of the poorest municipalities in the country), there are drugs, a military presence and immigrants, but there is nothing to eat. Even there they’re also developing resistance movements for education, for health and in defense of the rights of immigrants.” The Regional Council for the Development of the Me’phaa Peoples (Consejo Regional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Me’phaa), of the Ba’thaa language variation, has more than 17 apprehension orders open against its members as a result of its work defending the right of indigenous peoples to education and the right to development.

- In Xochistlahuaca, many stated, “Our hearts are bigger to have you here. We are exposed and we accept the risks. We have the legitimacy and that is what gives us an immediate defense.”