SIPAZ Activities (October 2005 – January 15, 2006)

31/01/2006

ANALYSIS: Mexico – Post-Election Uncertainties

31/07/2006

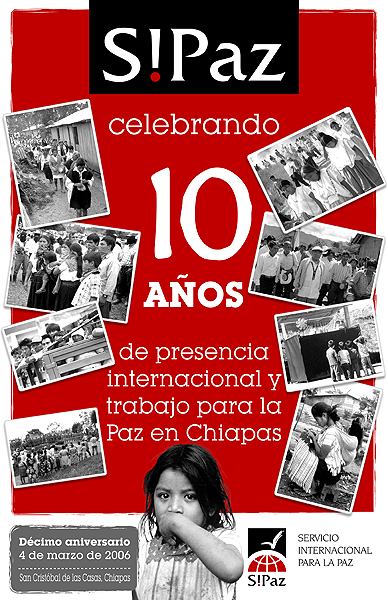

“SIPAZ,

10 years of hope,

10 years of effort,

10 years of experiences and experiencing,

10 years showing that dreams come alive through those who share them.

SIPAZ, or rather, the men and women who form it, have taught me so much. Among other things, the importance of taking small, steady steps to reach a distant destination (“making the path while walking”).

And to get there, it is more important to believe in the destination that to believe in oneself.”

(Testimony of Corinna, Germany, SIPAZ team member from 1998-1999)

> On March 4, 2006, SIPAZ celebrated 10 years of presence and accompaniment in Chiapas with an open forum for reflection on the “Current Challenges in International Accompaniment.” Among the participants were a number of our local counterparts, as well as international organizations working in this area in Mexico and Guatemala. It was an excellent opportunity to reflect on the lessons learned along the way as well as to affirm our commitment.

On March 4, 2006, SIPAZ celebrated 10 years of presence and accompaniment in Chiapas with an open forum for reflection on the “Current Challenges in International Accompaniment.” Among the participants were a number of our local counterparts, as well as international organizations working in this area in Mexico and Guatemala. It was an excellent opportunity to reflect on the lessons learned along the way as well as to affirm our commitment.

SIPAZ Step by Step…

The International Service for Peace emerged from a petition, issued by Mexican religious leaders and human rights organizations, presented to an international delegation that visited Chiapas in February 1995. With the goal of responding to the demand for a permanent international presence in the region, various organizations working in the area of peace, human rights and the peaceful transformation of conflicts, from the United States, Europe and Latin America decided to create a coalition united by a shared concern for the situation in Chiapas.

From 1995 to 1997

In its first phase, SIPAZ responded to a more “classic” strategy of intervention, mainly combining the international presence with the dissemination of information outside of the area of conflict.

The work of international presence and accompaniment has sought to limit and/or halt direct violence by raising the political stakes of repression against indigenous populations, through an international presence in the areas and moments of greater conflict. It is a question of playing a dissuasive role (the logic of “human shields“) in the face of possibly violent responses to the conflicts. A testimony from a resident of an indigenous community in the Northern Zone of Chiapas, in the first years of SIPAZ, directly reflects this function: “It is good that you visit us. If you visit us, they cannot repress us so easily, because the world will find out.”

To protect the work environment for human rights defenders, as well as the physical presence and observation, lobbying and political networking efforts have been carried out, with national authorities, embassies, and multilateral agencies.

The informative work has also played a complimentary role in terms of sensitizing and mobilizing the international community, which can, in turn, pressure those actors directly involved towards a solution through dialogue. Beyond limiting direct violence, by identifying the causes and consequences of the conflict, there is the goal of having an impact on the structural and systematic aspect of the conflict.

In the context of the anniversary, Ricardo Carvajal (Mexico, SIPAZ coordinator 1995-2001) recalled the example of the “North Station” project developed in collaboration with CONPAZ (Coordinator of Non-Governmental Organizations for Peace), the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center, the Indigenous Rights Center (CEDIAC) and Global Exchange (USA). This joint initiative, which maintained a physical presence in the area in 1996 and 1997, was able to compile a broad range of information regarding the increasing cases of human rights abuses. More than anything, however, it drew national and international attention to what was occurring in the region.

Jelle (Holland, SIPAZ team member from 1997-1998) still recalls intensely his participation in an observation mission carried out in Chenalhó in the weeks before the Acteal massacre in 1997: “We followed a muddy path across the hillside. It rained again. An hour and a half later, we arrived at a path where we encountered many people. Two wooden houses and hundreds of meters of plastic and leaf rooftops. The faces of discouraged people, eyes with distant gazes, into space, not seeing us. Shivering from the cold. There were hundreds of people under these roofs, who had been forced to flee their homes without clothing, without food, with nothing. All they had saved were their lives. When I returned home, I could not find the words to describe what I had seen. All I could find was the pain. A few days later we saw these images on a documentary on TV…” To be effective, it is important to make the situation known as broadly as possible, so that no authority can claim that they did not know what was happening.

In this first phase, the highest level of actors in conflict or track 1 (using the terminology of a multidirectional strategy) was apparently working or at least reinitiating it seemed possible. This is what occurred during the San Andrés Peace Dialogues until mid 1996 and, in the intermediary period that followed, a return to a similar format, with the implementation of the San Andrés Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture, was considered. The efforts of the primary and secondary actors were aimed in this direction.

From 1998 to 2000

With the stagnation of the peace process and the context of a strategy of Low Intensity Warfare, local conflicts multiplied. In the face of this situation and with the increasingly remote possibility of the reinitiation of the dialogue between the EZLN and the government, SIPAZ decided to open two new areas of work, more in the vein of track 2 (intermediary actors and towards the base). The idea was to limit the direct violence in the secondary community conflicts and to transform the context of cultural violence that could sustain them.

With the stagnation of the peace process and the context of a strategy of Low Intensity Warfare, local conflicts multiplied. In the face of this situation and with the increasingly remote possibility of the reinitiation of the dialogue between the EZLN and the government, SIPAZ decided to open two new areas of work, more in the vein of track 2 (intermediary actors and towards the base). The idea was to limit the direct violence in the secondary community conflicts and to transform the context of cultural violence that could sustain them.

In the area of Education for Peace, SIPAZ implemented a program with the goal of strengthening the capability of local actors in the construction of peace, particularly through workshops about the Transformation of Conflicts and Active Non-Violence. In this program, the participants included members of NGOs, indigenous organizations, and church groups, many of whom were able to increase their experiences in the communities in which they worked.

In the area of Inter-religious Dialogue, the goal was to see how religion could serve as a point of connection and dialogue between actors, rather than as another factor in the conflict. The ecumenical program of SIPAZ sought to encourage the local religious leaders, who so often had great influence, to take on the reconciliation effort as an imperative of their faith.

Miguel Alvarez, former member of the CONAI (National Commission of Intermediation, which mediated the dialogue between the EZLN and the government, and disappeared abruptly in 1998) recalls a lesson learned in these past 12 years: “We delayed in realizing that the work for peace was not simply at the negotiation table.” The strategic tour carried out by SIPAZ in 1998 aimed to address this issue. It became increasingly clearer that the strategy had to be more long term, in the truest sense of the “construction” of peace.

Miguel Alvarez, former member of the CONAI (National Commission of Intermediation, which mediated the dialogue between the EZLN and the government, and disappeared abruptly in 1998) recalls a lesson learned in these past 12 years: “We delayed in realizing that the work for peace was not simply at the negotiation table.” The strategic tour carried out by SIPAZ in 1998 aimed to address this issue. It became increasingly clearer that the strategy had to be more long term, in the truest sense of the “construction” of peace.

From 2001 to the Present

SIPAZ has continued to reinforce its progress from a logic of negative peace (absence of violence) to the construction of positive peace with intervention that seeks to continually become more thorough, and long-term, addressing the various dimensions of the conflict.

SIPAZ has continued to reinforce its progress from a logic of negative peace (absence of violence) to the construction of positive peace with intervention that seeks to continually become more thorough, and long-term, addressing the various dimensions of the conflict.

Today we have three areas of work:

- International presence in Chiapas and Mexico;

- Promotion and training for a culture of peace (Education for Peace, Inter-religious Dialogue, Networking);

- Sensitization about the causes, consequences and responses to the conflicts in Mexico (Information and Lobbying).

SIPAZ also maintains the areas previously explored, but with greater emphasis and a stronger connection/network in the national and international area. This change is due to a structural analysis that led us to understand the necessity of responding to national and international factors in the conflict. In this sense, it is worthwhile to mention the fact that starting in 2005, SIPAZ has worked to provide more direct coverage of the issues affecting the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. In the international arena, we are seeking to build connections with other networks and processes such as the Social Forums.

SIPAZ also maintains the areas previously explored, but with greater emphasis and a stronger connection/network in the national and international area. This change is due to a structural analysis that led us to understand the necessity of responding to national and international factors in the conflict. In this sense, it is worthwhile to mention the fact that starting in 2005, SIPAZ has worked to provide more direct coverage of the issues affecting the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. In the international arena, we are seeking to build connections with other networks and processes such as the Social Forums.

Lessons Learned Over 10 years

There are many lessons that we have learned over the past ten years: some came from moments of joy and hope, others from difficult and painful experiences.

Essential First Step: Halt the Violence

The pressure from the national and international civil society in distinct moments of the conflict in Chiapas have permitted the halting of violence and the opening of spaces in which to develop initiative for dialogue and the construction of peace at the local, national and international level. Even when the dissuasive effect had its limits (“negative peace“), the story would have been very different without this intervention (see, for example, “The Bridges of Words Constructed between the Civil Society and the EZLN,” SIPAZ Report, December 2003).

A Lesson in Humility

SIPAZ proposes itself as a “support agency” (SIPAZ Mission Statement). SIPAZ has never tried to explain to others how to resolve their conflicts. Nevertheless, the lesson of life often goes further, deconstructing the concept of “help“: Miriam (Holland, SIPAZ Team Member 2000-2001) wrote in her contribution to the tenth anniversary: “So many people, so much love, so many experiences that have helped me to find a direction and fulfillment in my life, up till now. I came to share my talents, my abilities, my training. Then I came back to my country, modest, realizing that it had been the other way around: the people there that had shaped me, that had taught me what is real, what love is, perseverance.”

“We should be the change we want to see in the world”

(Gandhi)

During the celebration, Gustavo Cabrera (Costa Rica, Service for Peace and Justice –SERPAJ- in Latin America, and member of the SIPAZ Board of Directors) made reference to this necessary congruence with the changes we propose to make outside “Adolfo Pérez Esquivel told a story: to distract his son, a man rips a piece of newspaper that has a picture of the world and asks his son to put it back together. The son manages to do so very quickly, because on the back there was a picture of a person. To fix the world, first we have to fix the people.”

Elena (France, SIPAZ team member 2005-2006) takes up this same point in a text she wrote for the anniversary: “That is what I will take with me from SIPAZ, in a corner of my heart. The sense that hospitality comes first. I do not know how they got to that. In our western cultures, it is not really something that we are taught. On the contrary, you first have to finish all your work, whatever it takes, spending the day in front of the computer until you see the world as pixels… I suppose that this sense of hospitality comes from a lot of acculturation, the sensitivity of each person, from their ability to listen to their heart, from many things really, a little of everything all at once… The relation comes first.”

Patience: Give Time Some Time

Heike (Germany, SIPAZ team member 1999-2005) insists on this issue a great deal, a very important part of the semi-permanent presence maintained in the Northern Zone. It all comes down to intercultural differences between, primarily western, team members. With a destroyed social fabric and in the face of the enormity of the violence that has occurred more in this area, relationships are built over time, until people feel the trust to be able to speak.

Phil McManus (USA, founder and president of the SIPAZ Board of Directors from 1995-2002) emphasizes: “An international team for peace that works in a polarized and violent situation has to confront a number of obstacles. It is one thing to be in a community, but it is another thing to gain entrance. In the particular case of the indigenous communities, who have survived 500 years after the conquest, it is, in part, because of their ability to close themselves off from outsiders. When the work requires that we talk with people on both sides, distrust increases and the challenge is greater.”

“A world where all the worlds can fit”: From Theory to Practice

In the various teams as well as in the work in the field (particularly if they are present in different places) we have seen the importance of everyone being able to express what they have lived, their version of the facts, even if it contradicts someone else’s version. John Paul Lederach (significant author in the School for the Transformation of Conflicts) often states that all those who are part of the problem have to work to find the solution. Once a meeting space of greater trust is established, it is easier to respect those who are we are faced with, without assuming a defensive attitude based in fear: “either you are with me or you are against me.” On the other hand, it is not about thinking everyone is the same, but rather the ability to work together, uniting efforts, within and from the differences.

The Mustard Seed Lesson

SIPAZ accompanied the dialogue process between Catholics and Evangelicals in Chenalhó (municipality where the Acteal massacre occurred) from 2000- 2004. It took a long time before the participants were able to realize that they are “brothers” of the same ethnicity and they are all Christians. It was possible to surpass the apparent victim/victimizer dichotomy to recognize that one way or another everyone has had their own pain in the conflict (the family members of prisoners, for example).

An anecdote that we often recall took place after the many difficulties of getting the parties to sit down and “break the ice“: all of a sudden, we saw Catholics and Presbyterians laughing together and talking enthusiastically. When we asked a translator what they were talking about, he responded “about ways to cook beans.” A trivial example but very reflective of the fact that we are never as far from the other as we think… José (Tzajalchen), one of the Catholic representatives participating in the process, commented after the workshop: “We shared how our lives have been since 1997. The closeness between brothers helps. Before we did not even greet each other.” Change starts there, in the “little things.”

Here… There…

Gustavo Cabrera (SIPAZ Board of Directors) emphasized the following point at the beginning of the celebration: “SIPAZ has developed new concepts of cross-culturalism, of joint actions between organizations and communities, in religious and communitary issues. An these contributions are valued throughout the world, they have been extended to experiences in Colombia and in North America. It is very important to value that this concrete experience, though apparently small, can have much greater significance in a broad context and it can contribute to the exercises for peace in other parts of the world.”

Marco (Italy, SIPAZ Team Member in 2000), sent us a greeting for the anniversary saying: “The international identity of SIPAZ and its commitment to the local presence are a prefect example of what global citizenship should be.”

Simply: Believing

In the 2003 SIPAZ Team we still recall, with great emotion, an interview with Jorge Santiago (former director of DESMI- Economic and Social Development of Indigenous Mexicans- and SIPAZ advisor) in which he gave us the strength to continue advancing despite a series of financial crises, with one simple word: believe, believe, despite everything. Marina (France, SIPAZ Team Member in 1997 and SIPAZ Coordinator since 2002) often cites John Paul Lederach, adapting his words to the Chiapan context: “Working for peace is like listening to the milpa (corn field) grow.” You do not necessarily hear it or see it. Nevertheless it is about continuing to sow seeds…

In light of the many lessons learned, SIPAZ is committed to following its path knowing it is surrounded by many others. Cecilia and Javier, close friends of the project, wrote to us from Spain: “Today the people of the Mesoamerican lands are walking ahead of us and behind us, they are walking beside us and their steps and our steps get confused but we do not get confused, our steps are the path, the path in which hope and happiness walk. That is to say, the best of what we have as humans, because the worst we have is what we go on breaking down everyday together with the people of Mesoamerica, we break it down with our hearts. This is why you and Chiapas have met and are walking together, and this is why it is important and necessary to continue walking together.”