ANALYSIS : Mexico – several movements of chess-pieces in Chiapas

24/02/2013

ARTICLE : Caretakers of the people and the land in light of barriers to effective participation of women and youth

24/02/2013Just 17 years after the signing of the San Andrés Accords on indigenous rights and culture, this between the Mexican federal government and the EZLN, the observance of these are honored in the breach. The stipulations of the Accords, which remain relevant today, have to do with the constitutional recognition and respect for the rights of the indigenous throughout the country, particularly those related to their territories. The Zapatista mobilization of December 2012 seeks to locate these rights within the national political agenda.

In other news, it should be stressed that in indigenous lands there has been seen a significant increase in the number of struggles in defense of territory, particularly in light of concessions for mining operations and different energy, touristic, and infrastructural projects.

Regardless, in November 2012 President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa submitted to the federal legislature a proposal of reform that seeks to streamline the processes for the privatization of collectively owned lands—a move that could become yet another aggression from the legal front. This could exacerbate the already difficult situation lived by campesinos in the country, promoting the social disintegration of this sector. It should be stressed that the rights of indigenous peoples would be directly harmed by this reform, given that the majority of the ejidos and communal lands are found on their territories, where—since before the Conquest—different forms of collective property have been observed.

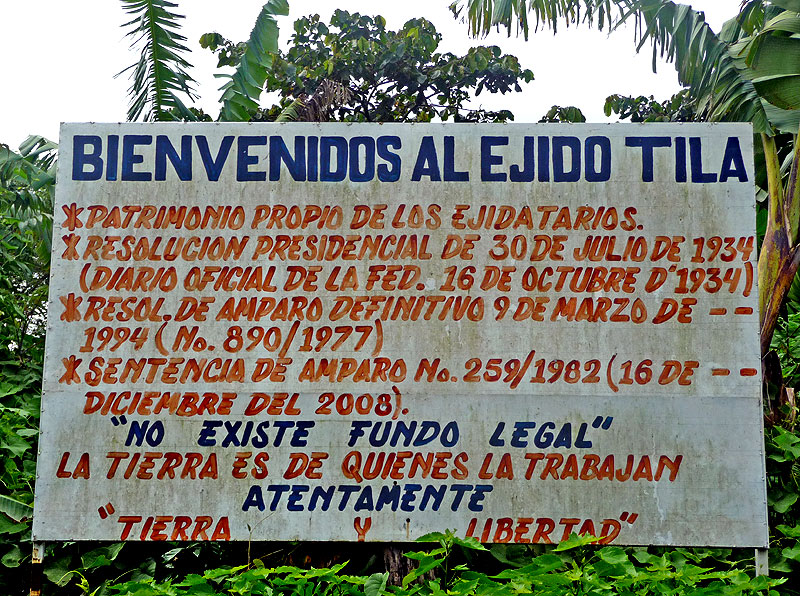

Within this context, the Supreme Court for Justice in the Nation (SCJN) once again accepted the proposal to consider the case regarding the lands of the Tila ejido in the northern zone of Chiapas: 130 hectares which the state authorities expropriated more than 30 years ago, for private use. The magistrates will discuss the protection that justice affords the ejido, which itself won a motion against the 1980 decree of expropriation.

What is presently being disputed

The Tila ejido was created in 1934, by means of a presidential resolution that did not define the lands that would be destined for an urban nucleus (or a legal foundation for such). It is important to stress this point, given that such a definition is a requisite for the introduction of foreign institutions into an ejido, such as a City Hall. Originally, the City Hall of this municipality was located in the nearby ejido of Petalcingo, but due to an epidemic, the City Hall was changed provisionally to Tila, where it subsequently was installed permanently on ejidal lands. In 1965, the ejidatarios undertook their first attempts to request that the justice system grant them protection, as it did, although the changes this sentence would demand were not carried out.

In 1980, the state authorities released a decree of expropriation in favor of the City Hall to establish its legal basis. Newly the ejidatarios resorted to the tribunals for protection. After more than two decades, in 2008, the motion was resolved in favor of the ejidatarios, and the immediate restitution of the lands to the ejido was demanded. However, at that moment the ejidatarios came to realize that their lawyer had promoted an alternative option whereby they would accept monetary compensation in place of the physical recovery of the lands. It is critical to note that, of the 130 hectares in dispute, only 52 bear construction on them, while the remaining 78 would serve cultivational purposes.

Since 2009, the ejidatarios of Tila have resorted to the political and legal struggle begun in the 1960’s, carrying out mobilizations in Tila, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, and Mexico City to demand their rights. Furthermore, these indigenous peoples (Ch’ol) have participated in different forums to raise awareness of their struggle and carried out numerous denunciations and public pronunciations over the course of these years. These last acts have coincided with the different stages of legal struggle that have even reached the SCJN, which presently has in its hands the decision regarding the restitution of rights or, alternately, to declare the impossibility of restoring these lands, instead promoting economic restitution, an option that the state government of Chiapas has also provided, without offering any alternative.

Obstacles to overcome: power-struggles and interests that seek to overwhelm the ejido

Since at least two decades ago, the Northern Zone of Chiapas has been of political and economic interest for different actors, both state and non-state, beyond the population that resides within the valleys and mountains of the region. Within the most recent history, two elements that have affected the struggle of the ejidatarios of Tila must be stressed: the development of “low-intensity warfare” following the Zapatista insurrection in the region, and the political and economic interests of local actors.

The Tila ejido, which gives its name to the municipality of the zone, forms part of this region in which live indigenous Ch’oles by majority. Toward the end of the Spanish viceroyalty (the eighteenth century), the creole and mestizo populations pressured authorities to obtain lands for themselves, and in this way “began the process of looting of the lands of the Ch’oles.”1. The kaxlanes (mestizos) established themselves in large populations, while indigenous communities remained relatively isolated. At the end of the nineteenth century, the lands of the communities were divided into private parcels, and subsequently the region was opened to foreign capital (principally German and U.S.). “The ranches were constructed as the center of the economy of the Northern Zone. The drivers were agro-export firms […]. Though a large part of the German and North American firms exploited a variety of agricultural products, coffee was the focus of their negotiations. Coffee-farms in the Northern Zone physically occupied the entirety of the Ch’ol population, leaving peoples without ejidos and the grand majority of indigenous people without their own land. One of these farms, El Triunfo, occupied more than three-fourths of the modern territory of the Tumbalá municipality” (ibid).

During the Mexican Revolution and the first two decades of the twentieth century, the semi-feudal structures of land tenancy continued in the region to be largely intact. This situation was not remedied until the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940), when in parts of Chiapas land reforms were enacted. In the Northern Zone, the lands granted to campesinos were either public or private, belonging to foreign capital. This is the context within which was publicly decreed the Tila ejido.

During the subsequent decades, with lands obtained via presidential decree, communities in the Ch’ol zone dedicated their efforts principally to their milpas, or sustenance farming, coming in the 1970s and 1980s to the cultivation of coffee; regardless, the commercialization of this cash crop remained in the hands of the kaxlanes. Different factors contributed to the fact that, at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, a small group of leaders from certain communities considered themselves to be allied to the federal and state governments—principally because they received government support and/or were a part of the political or party structure of the government—while other peoples felt abandoned by the authorities, thus coming to oppose the PRI.

Following the EZLN’s uprising, these differences became radicalized and led to one of the bloodiest episodes within the Northern Zone, particularly the Tila municipality, one that civil organizations have named a “war of low intensity.” As part of this strategy taken on by the State to confront the EZLN, there has been indicated the formation of paramilitary groups: in the Ch’ol region, beginning in the first half of 1995, one of these was named Development, Peace, and Justice, or better known as Peace and Justice. As a consequence, militarization increased greatly in the region. Several sources, including the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC), have accused the Army of being accomplices of Peace and Justice during this time. The founding and operating style of the group were linked to the Tila municipality and its City Hall.

In the elections for mayor and deputies to the local Congress, Marcos Albino Torres López – leader of Peace and Justice in Tila – was elected head of City Hall, while Samuel Sánchez Sánchez, one of the founders of the group, won a position as deputy for the VIII electoral district, based in Tila, Sabanilla, Tumbalá, and Yajalón. As the CDHFBC noted near the end of 1995, “Samuel Sánchez Sánchez directed either directly or indirectly those involved with Peace and Justice and the Tila municipal police, with the help of Marcos Albino Torres López.”

© SIPAZ

The ejidatarios have insisted in indicating members of Peace and Justice as opponents of the ejido. “They are the ones who take our land and do not want us to fight to defend it.” The conflict with this group also took place in the Tila ejido, “in 1996 and 1997 there was […] a great deal of intimidation among the people as prosecuted by this group […]. [M]any people did not want to leave their homes.” Peace and Justice is mentioned as having been financed by projects of the municipality and state governments. In October 2000, eleven members of the group were arrested, including its two main directors, Samuel Sánchez and Marcos Albino Torres. They were charged with presumably being responsible for the crimes of terrorism, mutiny, criminal association, organized crime, carrying of firearms of exclusive Army and Air Force use, damage, and looting.2 These detentions were of a very limited character regarding the successes gained by the organization in the area. Recently, ejidatarios have noted that members of Peace and Justice have started to become an integral part of the local political class.

There exist other elements that play roles in this dispute between ejidatarios and municipal and state authorities. It should be recalled that the sanctuary of the Señor de Tila is found there which has been and continues to be the destination of many pilgrims. These pilgrimages represent important economic benefits which have to date been collected largely by municipal authorities. Furthermore, merchants from outside have settled in Tila to establish commerce there, and these new residents (who have no ejidal rights) have traditionally been allied to the municipal City Hall, “with their own economic and political interests.” This is a factor that influences the dispute between the ejidatarios and City Hall.

Regardless, there is no will on the part of ejidatarios to expel residents from outside if it is that they should recover control over their lands. They say that they respect those who live in the municipality, as long as they observe the rules of the ejido. “What we do request is that the offices of City Hall be relocated to another place, because instead of benefiting us they have brought us insecurity. Every three years small groups fight among themselves in the elections and terrorize the indigenous people. We have had enough of this injustice; we demand respect for the right that is ours by right as an ejido and Ch’ol indigenous people.”

© SIPAZ

Lastly, it is important to discuss the presence of the Mexican Army. In response to the Zapatista insurrection, and as part of a governmental strategy of counter-insurgency, a military camp was installed on the ejidal lands, at the exit of Tila city. This was made possible also because of the control that the City Hall had exercised over the community’s lands. In a region such as Tila, in which there has been seen the construction of a process of autonomy on the part of the EZLN, the presence of the military has functioned as an element of social control over parts of the populace that are in resistance, given that it could intervene whenever there might emerge protests or other disturbances. It is clear that, in the case that the ejido does recover its lands, it could decide to demand that the Army abandon its lands.

As we have seen, the struggles of the ejidatarios of Tila for land have lasted decades. 40 years passed since the request for the lands until they received the documents confirming their possession over such. Then came a legal battle to preserve the integrity of their territory, against the decree of expropriation undertaken by the state government in 1980. The case has passed from the hands of judges and tribunals, coming finally to the SCJN, which must now make a decision.

Beyond juridical resources, the ejidatarios have made use of other tools in this struggle, such as public denunciation, solidarity with other movements that have confronted similar problems, and the raising of awareness of their case in public events. They hope that justice is delivered to them as an ejido and as Ch’ol indigenous people. There exists much judicial evidence that could assist in this struggle. The reform of the Political Constitution of the Mexican United States with regard to human rights in 2011 stipulated the harmonization of the Supreme Law with the international accords signed by Mexico in terms of human rights. The SCJN now has at its disposal the opportunity to confirm this reform: it is a question of indigenous peoples that must be evaluated not only with reference to the Mexican Constitution, but also with ILO’s Convention 169 and the Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, opting at every moment for the decision that would be most helpful for indigenous peoples.

A decision with possible implications at the national level

If the SCJN’s decision is a favorable one, the Ch’oles would have control over the totality of their territory returned as corresponds to them, in accordance with the official documents that have been indicated. Thus would be ended a large dispute among ejidatarios, on the one hand, and municipal and state authorities, on the other. The multiplicity of actors and interests, both internal and external, vis-a-vis ejidos is not a reality that corresponds only to the Tila ejida, nor one that can be limited to recent dates. It should be recalled that the unjust distribution and lack of lands available for cultivation was, for a great deal of indigenous and campesino peoples, the very reason to join different revolutionary forces beginning in 1910. One of the results of the Mexican Revolution was the constitutional protection of the two forms of social and collective possession of land: communal goods and ejidal lands, as stipulated in article 27 of the Mexican Constitution. These lands were declared as ones that could not be bought or sold. The beginning of the struggle of the Ch’ol indigenous people for their land occurred within this historical context. Starting in 1922, the date in which was presented the request for the lands that today make up the ejido, it advanced significantly in 1934 with the presidential decree that awarded these lands official ejidal status.

The protection of collective property was reduced for the first time with the reform of article 127 in 1992, thus opening the possibility that ejidatarios, by means of general assemblies of the ejidos, might become owners of their individual plots and the ejidal lands that corresponded to these. This process was facilitated by governmental programs such as Program of Certification of Ejidal Rights and Titulation of Urban Plots (PROCEDE), and more recently the Fund for Support for Agrarian Nuclei without Regulation (FANAR). However such reforms to date have left the general structure of the ejidos intact, allowing their constituent members to maintain the ejido if they decide to do so.

The initiative of the law of Calderón consists in a series of changes to the Agrarian Law, which defines the specific rules for article 27, these being modifications that would convert the ejido into private property. As is indicated by the analyst Francisco López Bárcenas, the ejidatarios would transition from being possessors of the land to becoming its owners. The ejidal assembly, given such changes, would lose control over the land, given that with their passing to become private parcels, property owners would not need to request authorization of the assembly to carry out whatever activity on their own property.3 In this sense, López Barcenas affirms that the proposal made by Calderón could reverse the successes of the historical struggle for the land in Mexico, and indeed would signify a serious regression for a large part of the population, being rural, as it would do away with one of the most important social victories of the Mexican Revolution.

With the possibility that the federal legislature might decide to approve Calderón’s initiative and so accelerate the process of privatization of the collective property in land, a favorable decision by the SCJN could provide a signal of protection for the rights of a vulnerable sector: indigenous peoples. It would be transcendental on other grounds, as it would apply to the constitutional reform in human rights, providing the broadest protection. It would be a decision in conformity with the San Andrés Accords, which some parts of the Mexican political class have recently recognized as being a debt owed to the indigenous of Mexico. This move would do justice to the Ch’ol people of Tila, and it would also open the door of the system of justice to the other indigenous peoples of the country who struggle against looting and for their right to the land.

Read more (in spanish):

![]() Documento amplio: El ejido de Tila y su lucha por la tierra bytes

Documento amplio: El ejido de Tila y su lucha por la tierra bytes

- Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (1996). Ni Paz Ni Justicia.. (^^^)

- La política Genocida en el conflicto armado en Chiapas, 2001 (Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights) (^^^)

- Francisco López Bárcenas (2012) Adiós al Ejido, La Jornada – november 20, 2012. (^^^)

Documento amplio – El ejido de Tila y su lucha por la tierra