ANALYSIS: The Ayotzinapa case, a check against the authorities

21/02/2015ARTICLE: “Faces of Pillage” – Campaign in Solidarity with the Displaced from Viejo Velasco, Banavil, and San Marcos Avilés, Chiapas

21/02/2015“Investigative work is risky. These are issues that challenge the situation of those in high-ranking positions. We do this out of conviction, but it is a very risky type of journalism. The accusation is what puts us at risk. We prove who commits the violation [in question]. This is not because we are left-wing, but because we are investigators.”

Zósimo Camacho, Contralínea

For several years, Mexico has had the infamous notoriety of being one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists. In a February 2015 report, the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) and Peace Brigades International (PBI) affirm that “[d]uring the first nine months of 2014, the Mexican section of the international organization “Article 19″ documented 222 aggressions against journalists.” Between 2007 and 2013, Article 19 registered more than a hundred journalists murdered in Mexico, principally in the northern states, as well as in Veracruz, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. The beginning of 2015 does not present evidence of any change given the disappearance and murder of the Veracruz journalist Moisés Sánchez in the first weeks of January and the death-threats in the following weeks directed against two journalists in the same state. Moisés Sánchez worked for La Unión newspaper in Medellín, Veracruz denouncing criminal proceedings and corruption among the authorities. Francisco Sandoval, an Article 19 journalist , says that there is an alarming tendency: two out of three documented attacks (labeled as “not serious”) were committed by public officials. In addition, there is clear collusion between organized crime and State authorities.

In the report “Dissenting in Silence: Violence against Journalists and the Criminalization of Protest, Mexico 2013”, Article 19 documents more than 60 attacks against journalists that took place during protests. This indicates that “the authorities opt for the path of repression and direct confrontation.” In nearly 60% of the cases, a public official was responsible for the attacks. Members of the House of the Rights of Journalists in Mexico City are monitoring on a daily basis the increase to an average of 12 or 13 daily attacks on journalists, including cyber-attacks, physical harassment, robbery, and death-threats, among other forms of violence.

Violence targeting female journalists

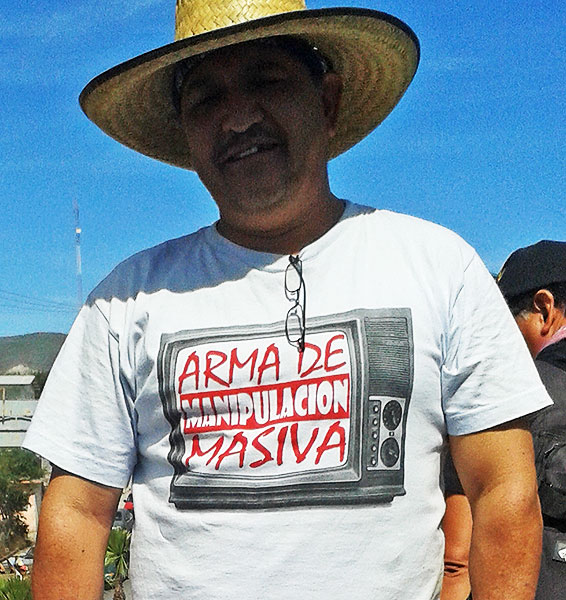

© Plumas Libres

Taking into account the fact that there are more men than women in the world of journalism, the majority of the violent incidents are against male journalists. However, in an interview held with SIPAZ, Omar Rábago Vital, director of the National Center for Social Communication (CENCOS), stated that there are important differences between the violence directed against male and female journalists. Violence against men is physical, including beatings, kidnappings, and even murders. While for women it is more common to see death-threats directed at her family, sexual assaults, insults, and discrediting attacks to her or her work. In addition, female journalists face sexual harassment in the workplace. It must be noted that within the hierarchical sphere of journalism, very few women work in top positions.

According to the 2014 Report for Communication and Information for Women AC (CIMAC) on “Impunity and Violence against Female Journalists: A Legal Analysis,” violence against female journalists is on the rise despite measures that have been taken to prevent this. There are several official institutions and many resources dedicated to the problem, but these processes have not led to a decline in rates of violence much less to their elimination. This reports explains that, between 2012 and 2013, 86 cases of violence against female journalists were registered in Mexico. All of the cases involved psychological violence In 75% of the cases, journalists were attacked directly by public officials, mostly state government officials, which “translated automatically into perpetuated impunity.”. Furthermore, the report carefully analyzes four cases of violence against female journalists, focusing on the ways in which the media sheds light on the problem: “According to the Media Observatory of CIMAC, the official story always remains distant from the commitment of journalism to investigate. These affirmations are reproduced by the mass-media without question, leading to the false and sexist judgment of women in the social imaginary.”

Érika Ramírez, an investigative journalist from the weekly journal Contralínea, directly experienced violence in April 2010, when she was accompanying a caravan to the community of San Juan Copala Oaxaca. The caravan was ambushed by an armed group leading to the deaths of two members of the caravan, of Jyri Jaakkola and Bety Cariño. Together with three others, Érika was able to escape the attack even though her car was hit by 64 gunshots. The four escapees remained hidden in the mountains for 72 hours before they were rescued. As Érika relates, “afterward, I had a great deal of adrenaline, because I survived. I thought much of my son; I was afraid to lose him. My family told me: ‘please stop this kind of work; think of your child.’ But I do think of my child, and this is what I want to teach him: to have a strong social commitment. After the fear, my adrenaline spiked causing my desire to continue working on this because many people experience this [violence] every day. I returned to the area two years later, and it was good for me as I was able to transcend my fear. In this type of work, you cannot be afraid.”

The Contralínea case: at risk due to its social commitment

Contralínea is one of the communications media that has received the most legal complaints. After having experienced several cases of death-threats and harassment, Contralínea was the first communication group to take precautionary measures from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). In an interview with SIPAZ, Zósimo Camacho, the coordinator of information for the periodical, spoke of the profound inequalities among different sectors of Mexico’s populace. He mentioned that when one looks at how certain individuals and firms prosper in Mexico, he concludes, “wealth of such magnitude must be the result of the plundering of someone else.” This conviction leads him to intensely investigate and report on cases. In Contralínea there are two divisions: one that investigates accountability of the three branches of government and the other dedicated to human rights. Making visible the cases of nepotism, corruption, and human-rights violations puts the weekly journal’s reporters at risk. The group has been subjected to several forms of harassment including a recent public auditing that has complicated its financial situation. In June 2014, its offices in Mexico City were forcibly entered and information and technical equipment was stolen. Nonetheless, Camacho emphasizes the spirit and conviction of its members to continue investigative journalism.

The Mechanism for Protection of Journalists: it leaves much to be desired

The PBI and WOLA February 2015 report claims that the Mexican Secretariat of the Interior’s Mechanism for the Protection of Human-Rights Defenders (the Mechanism), which was created in 2012, “does not work” and as a result of its deficiencies, those who have sought its support have not been able to receive any guarantee of security,. In the report groups indicate that the organization continues to face numerous challenges and shortcomings. These deficiencies include a lack of personnel, resources and the inability to respond opportunely and efficiently to urgent petitions. The implementation of security measures often depends in large part on support from state and federal governments.

Beyond having impelled the creation of the Mechanism, Article 19 was similarly awarded precautionary measures after it received an anonymous letter containing a direct death-threat against the director and members of the organization. Ultimately, though, the Mechanism proposed the cancellation of measures of protection claiming that the risk faced by Article 19 is low because “nothing serious” happened. However, in its 2013 report on “Dissenting in Silence,” Article 19 affirms that after the anonymous letter, it confronted at least seven other security incidents.

Oaxaca: special risks for female human-rights defenders

Oaxaca is one of the most dangerous states to practice journalism in Mexico, especially for female activists defending freedom of expression. In February 2015, the Network of Female Activists and Human-Rights Defenders of Oaxaca, comprised of 100 female human rights defenders, expressed their concern regarding the serious rise in the number of attacks against female human right defenders and journalists in Oaxaca. It says that “since 2010 […], Oaxaca has become number one in terms of attacks at the national level. It is still very grave that the number of such attacks continue to rise. While in 2012 48 attacks were registered, there were 122 attacks in 2013 and 198 in 2014.” As an example, in August 2014, female journalists and organizations from Oaxaca condemned separate attacks against three female. In a communiqué, they stressed “the insecurity that is experienced in the state of Oaxaca has placed female journalists in an insecure state. Not only are safe working conditions guaranteed, but there is also a lack of effective actions for non-repetition […]. The [CIMAC] Report shows that Oaxaca, Chiapas and Puebla, share the fourth place on the attacks on female journalists in the nation.”

Chiapas – “Destabilizing journalism”

© SIPAZ

There exist risks in Chiapas for female journalists. As Chiapas Paralelo denounced on 2 February, the authorities have imposed a strategy to damage and defame “rebellious journalists” on social media. The practices of libel, death-threats, and harassment targeting journalists are nothing new. The article tells about ex-governor Juan Sabines, who harassed journalists, and Pablo Salazar, whose legacy has been “tarnished by the unjust persecution of editors of the [state newspapers] Cuarto Poder and El Orbe.” It also identifies a similar practice utilized by present Governor Manuel Velasco, who “listens to those voices that advise him to defame certain journalists, imprison them, and make their lives impossible.” On other recent occasions, the journalist Ángeles Mariscal, also from Chiapas Paralelo, was accused of launching a “dirty war” on social media when she indicated the violation of Article 33 of the Mexican Constitution by those who participated in the videotaping of five foreigners who claim to be tourists campaigning for a local deputy. According to Mexican law, foreigners cannot participate in the internal politics of the country so that their public support for public officials is not permitted.

Guerrero: freedom of expression repressed in protests

In Guerrero, the situation is equally precarious. Recently, there were several incidents of repression of protests and journalists demanding the appearance of the disappeared Ayotzinapa students. For example, on November 11th, police beat journalist Carlos Navarrete from the El Sur daily and attacked at least 10 other journalists who were documenting the violent displacement of 500 teachers from the State Coordination of Educational Workers in Guerrero (CETEG) from the PRI offices in Chilpancingo. Article 19 called for the State Police of Guerrero to adopt the necessary measures to guarantee effective protection of rights “within the context of public protests or mobilizations, including updated protocols for public security forces and other authorities observing their responsibility to prevent and protect against any attack against journalists, protestors and those who cover said actions.”

Self-care for journalists

In its 2014 report, CIMAC declares that the constant attacks on freedom of expression in Mexico have led many journalists and communications media to stop publication of news articles covering corruption or organized crime thus depriving Mexican society of critical information. One response to self-censorship has been the surge in websites where people anonymously upload information regarding sensitive matters. This method of journalism works in states like Veracruz and Tamaulipas which have high levels of violence from organized crime. It also works in states like Chiapas, where repression and censorship of traditional communications media comes mostly from government officials. Ángeles Mariscal says that, “thanks to the Internet, professional journalism can be practiced. Previously, due to the high prices of printed newspapers, there was the need for sponsors which usually ended up being the state government. Now the dream of all professional journalists is made concrete through social networks and websites.” Another way to prevent the increase in self-censorship is the strategy of signing articles with the “Editorial” byline thus protecting the identity of writers.

In 2010, amidst grave insecurity, a group of journalists and expert human-rights lawyers created the House for Journalists’ Rights. One of the founders, Víctor Ruíz Arrazola, noted in an interview with SIPAZ that protective defense and prevention for journalists has been lacking. For this reason, a refuge has been created in Mexico City where at-risk journalists can go to stay for an extended length necessary. Journalists are not required to file a penal denunciation to be allowed to stay there. “We have done risk analysis to see how we can help, and what conditions are needed to be able to return to journalistic work. The goal is to prevent them from cornering us, and then for us to abandon the work,” Víctor Ruíz explained. Close to 20 journalists have been received at the House over the past 3 years. The majority of them are from Veracruz, Michoacán, Guerrero, Mexico City, Durango, Chihuahua, and Sinaloa.

Preparation is the most important asset necessary to practice journalism in the safest way possible, notes Érika Ramírez. “You have to know what not to do. For example, do not to go in front of a march, even if one wants to take photos. We have to be physically and emotionally prepared. Often we do not do take into account our security. I survived three days in the mountains because I was physically fit. We must be in constant communication. In the case of San Juan Copala, we left a list of telephone numbers in case of emergency., They could quickly find us, because we were able to contact someone on the list.” Her colleague Zósimo Camacho considers security courses to be equally important although the recommendations are often not observed. He says, “sometimes the courses recommended that we ‘not go,’ but that is not possible for us. In Copala we said that we would not pass the checkpoint, but we did want to go. There is no news that is worth a life. It is not worth risking one’s life. But the ambush happened before the checkpoint.”

To be prepared, Ángeles Mariscal describes, journalists need to have a network of allies for protection. Today there exists a broad network of journalists in Mexico and abroad. According to her, “the best protection is to have good practices. If you do your work well, people will build a network with you. If we do not have solidarity among the people, we cannot continue our work.”

Freedom of expression in Mexico is currently under fire due to the numerous beatings its defenders have suffered. Journalists are being kidnapped and murdered; anonymous bloggers are persecuted. Community-based radios have stopped their work after receiving threats, and journalists are being subjected to defamatory campaigns. Such situations have been occurring for years in our country on a daily basis. This implies that society in general does not have access to truthful and comprehensive information. It is important to recognize the courage of journalists, both professional journalists as well as citizen journalists. In addition to a free and alternative media. It is the daily work of journalists to distribute information so that society has a better notion of what is going on in communities, states, and country. The last word is left for Ángeles Mariscal: “We are put at risk, but we do not leave our work. The common good is the right of society.”