“All the methods that [indigenous] peoples traditionally use to judge crimes committed against their members should be respected.”

“This Constitution recognizes and guarantees the right of indigenous peoples and communities to free self-determination and, as a consequence, to autonomy for . . . the application of their own normative systems in the regulation and solution of their internal conflicts.”

Justice is one of the areas in which indigenous peoples can exercise their autonomy and their right to free self-determination – that is to say, to freely decide and implement their own governance systems. Several texts have ratified the recognition of this right, specifically, Convention 169 of Indigenous and Tribal Persons of the International Labor Organization on Indigenous and Tribal Persons (1989, ratified by Mexico the following year), the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as well as the Mexican Constitution.

Indigenous communities have appropriated the traditional forms of exercising justice and resolving internal conflicts. They are well within their established rights to do so. This serves as a distancing mechanism from the official justice system imposed by state or federal authorities whose goal is not always what is “just” for indigenous peoples.

In Western societies, the most commonly held notion of justice is decided and administered by the State in retribution for crimes committed against individuals, property or the State. The State declares that justice is neutral and meted out impartially, and that laws are egalitarian in nature. The focus is on determining guilt or innocence so that punishment may be meted out accordingly. Punishment serves the dual purpose of accountability for one’s crimes and to deter others from committing the same crime.

As it turns out, this is not true justice for everyone.

On the other hand, restorative justice – also known as “healthy,” “transformative,” “repairing,” or “reintegrating” – is based on an altogether different vision of justice. It differs from the Western conception of retributive justice, whose end is to impose punishment as a response to questionable behavior. Restorative justice first asks the question, “Who has been harmed?”, and seeks to reestablish broken relationships, both between victim and perpetrator as well as within a given community as a whole.

Another goal of justice

The practice of reconciliation and mediation implied in restorative justice differs from those advanced by the State in three key areas: in the way of considering the act, in the manner of thinking of punishment, and lastly in the way that punishment is applied. The goal of restorative justice is to come to an agreement in which both parties feel satisfied. The crime is not perceived only as an offense that broke a law, but rather, an action that also hurt a person and a community. Interpersonal dimensions are central. Once the social fabric has been damaged, it becomes necessary to restore harmony through a process of recovery and restoration.

The ultimate goal of restorative justice is to construct peace in the long term. “Justice is the path toward peace, but […] only the justice that restores and recovers is the one that can sow true peace,” notes Willi Hugo Pérez, a Mennonite leader of SEMILLA (Latinamerican Anabaptist Seminary) in Guatemala. A true and lasting solution should seek to avoid future conflicts. If one of the parties is not satisfied with the accord, this can result in a downward spiral of rage and vengeance. Justice is considered to have been done once “the responsibilities have been assumed, when the needs have met, and when re-establishment has taken place both on the interpersonal as well as individual levels” (Lemonne, 2002). This can be achieved using the cooperation of all the members of the process through an interpersonal dialogue, toward the end of recognizing the needs of all involved parties.

The penal process does not attach much importance to how the victim feels, much less how the offender feels – nor does it take into account the needs of either. But the practices of mediation and reconciliation recognize the importance of all sharing their views, both the victim as well as the offender, and also the community at large, which suffers a loss of harmony.

In a restorative process, the victim is considered and validated, taking into account what s/he has suffered and what s/he needs to return to a life with trust and without fear. It is recognized that, on the psychological level, victims of a crime need space and time to have their pain and suffering heard and recognized. The Peoples’ Permanent Tribunal is a mechanism that allows for the people to denounce grave human-rights violations when conventional judicial means have been exhausted. Despite not having an executive function of justice, merely speaking out about victims and presenting “symbolic” sentences does much for reconciliation and peace in the long term.

The restorative perspective differs in its treatment of criminal suspects, as it gives them the opportunity to give their version and to be heard alongside the other implicated parties. The mediator accompanies them in a process to repair, as much as possible, the harm that was caused, including penance and reparation of damages. It is fundamental that the perpetrator acknowledge what he or she has done. This offers the possibility of forgiveness within the restorative model. Traditional indigenous justice does not tend easily forget harm or conflict. But by allowing for a second chance through a process of taking conscious responsibility, this approach works to heal relationships and the reduces the risk of a recurrence.

Examples of the implementation of restorative justice: the Tseltal vision of justice, an example from Guerrero, and the “other” justice

As an assessor of CORECO (Commission of Support for Communal Unity and Reconciliation A.C.) who works in Chiapas explains, the Lekil Chahpanel (“the good agreement” in Tseltal) is the basis of the culture of the “grandparents” in indigenous communities. Toward the end that harmony be maintained or returned when there are conflicts, for years this historical form of making justice has been implemented – not with judges, but with mediators; not with sentencing, but with agreements; not with punishments, but with reparations. CEDIAC (the Center for Indigenous Law A.C.) is another example of how the Tseltales in the Chilón area have retaken the traditional indigenous manner of arranging their problems internally, “returning to harmony among the different parts and the whole,” using the help of jMeltas’anwanej (a Tseltal term that means “reconcilers” or “arrangers” of conflicts).

Toward the end of implementing justice that is more adapted to the context and their way of seeing things, some communities have created reconciliation commissions with the elders who are “the ones who know how to resolve problems” and to secure reconciliation. The figure of the mediator replaces that of the judge: s/he is not there to judge or pass down a sentence, but rather to understand what happened, and to ensure that all agree to the Lekil Chahpanel. This Tseltal term is derived from the Word Lekil, “what is very good,” and Chahp, the root of the verb “to arrange.” It can thus be understood as a good arrangement. It is the Tseltal way of seeing justice coming from the roots and the just way of imposing sanction.

The process consists in “restoring something that has been disturbed,” as a member of SERAPAZ (Services and Assessment for Peace) explains. In these cases, the harmony of the community and the relationships among individuals has been disturbed and must be restored. The spirit of unity is always at hand, and the Lekil Chahpanel is always sought as a means of living together well (Lekil kuxlejal) and in peace (slamalil k’inal).

In each phase, the consent of all is sought, given that there can be no good justice which is imposed. Nor can peace be imposed – it must instead be the fruit of collective work. It takes time to achieve. The SERAPAZ assessors point to the success of this process, given that “it is an inclusive process and the agreements are long-lasting, because they were taken in common without discriminating against anyone.” They cite the example of a man who died during an accident while a relative was giving him a ride. To the widow, the driver offered to pay for the funeral and take responsibility for the costs of raising the children (health, education) who would be fatherless, as a means of repairing and compensating what he did, even though it was unintentional.

Another example of alternative justice is found in Guerrero, where since the 1990s there has existed the System for Security, Justice, and Communal Re-education, as managed autonomously by the communal police. The CRAC-PC (Regional Coordination of Communal Authorities-Communal Police) was born of the lack of satisfaction of the peoples amidst the absence of response from authorities in light of the violence which gripped the region. At present, this initiative is involved in the national debate on self-defense groups. Said groups have emerged from citizens who are tired of seeing the inefficacy or indifference of the government amidst violence and impunity and so organize themselves and create their own armed forces to defend themselves and confront organized crime. If it is true that the CRAC-PC began for the same reasons, it cannot be compared with the self-defense groups because it is not only an armed group that guarantees security, but rather a true entity that was founded to implement justice from a restorative perspective, thus affirming traditional indigenous practices, with decisions taken in assemblies. This is a broader perspective of autonomy.

The first phase was the initialization of its own security system: the communal police. The armed volunteers, elected by their communities, began to supervise the zone and hand over criminals to the official authorities. Slowly, however, they came to realize that the state justice system was inefficient and corrupt, given that delinquents were released easily and rapidly from jail on bail. In this way, dissatisfaction grew with the failures of this type of justice, which was expensive and hard to understand, particularly given that many communities do not speak Spanish as a primary language.

From this was born a second phase in 1998: an autonomous system to provide and administer justice through the CRAC, whose principles are to “investigate before processing, reconcile before sentencing, and re-educate before punishing.” It imparts justice without monetary cost in traditional languages that are understood by all, and following the traditional indigenous forms of resolution of conflicts – that is to say, by collectively finding reconciliation. The punishments that are imposed onto criminals include collective work in communities, and in addition there exists a true work of re-education, which consists in accompanying the delinquent in an exercise of reflecting on his or her action. The CRAC manages a broad spectrum of crimes and infractions, given that it even judges cases of murder and rape. The statistics of crime in the regions in which this system of justice has been implemented have dropped significantly, thus demonstrating the efficacy of this system.

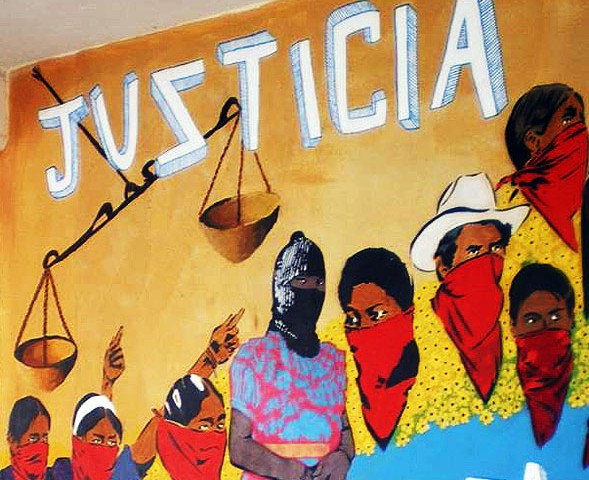

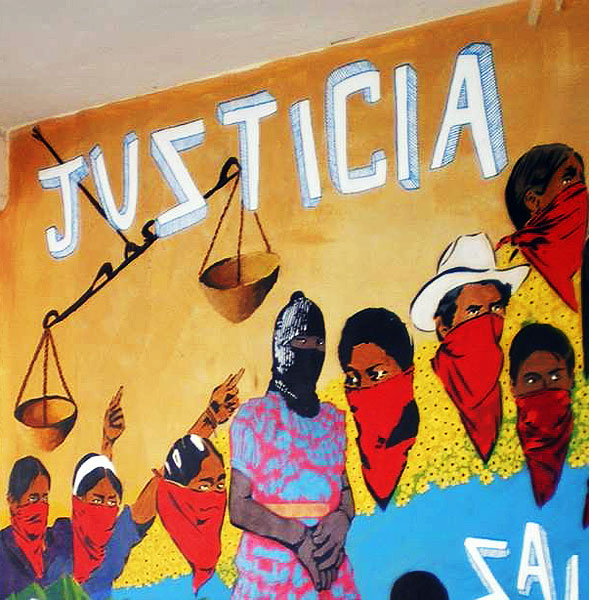

Beyond this, the support-bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN) have their own systems of government, health, education, and justice. The “other justice” imparted by the Good-Government Councils (JBGs) is based on the recovery of the traditions of their ancestors: its foundational principle is reconciliation in the first instance as a means of resolving conflicts “in a good manner.” As in all contexts of reconciliation, the goal is to promote healing and come to a collective agreement, although he or she who is responsible for a crime must recognize and compensate for such – not with money but rather through collective work that will serve the local community.

In the textbooks of the Escuelita (“little school”), the BAEZLN provide concrete examples of how they have solved problems they confront in their communities, such as the presence of polleros (individuals who do business trafficking undocumented migrants) in their territories. “Instead of throwing them in jail, we make them work,” they declared with respect to one pollero who stayed for six months building a bridge that would facilitate access to an autonomous hospital. In place of being a punishment only, the punishment is work that benefits the community. The judged person is given an opportunity to repair the damage s/he caused to the community.

The tribunals located in the Caracoles (Zapatista autonomous political spaces) also have judicial function in the autonomous communities, and they document and hand down sentences. They seek alternative solutions to the denunciations before the official Public Ministry. They provide justice services not only to BAEZLN but also to those who do not pertain to the Zapatista organization. This indicates both the need but also the recognition of this kind of reconciliatory system of justice.

This form of making justice, nonetheless, has limits, and not only among the BAEZLN. As a member of the organization notes in a video from the Escuelita, they lack solutions and systematic ways to manage cases of a graver nature, such as murders or rapes.

A system that can still improve

In the restorative system of justice, as in many other areas, women’s participation continues to be an important problem. Some women do participate in assemblies, but not many. The councils for justice are mixed-gender; the wife of the jMeltas’anwanej (mediator or reconciler) also attends all phases of the process. Nonetheless, women’s participation “independent of the charges of their husbands who share responsibility with them” is on the rise.

Another obstacle is the proper government itself, which does not necessarily see the challenges to its authority and system of justice in a good light. In the case of the CRAC-PC of Guerrero, several members have been arrested, and to date 13 remain imprisoned. The employment of alternative justice brings to light the failures and corruption that permeate the governmental institution.

Restorative justice equally has its own limitations that are related to the crisis suffered by communities themselves. Members of CEDIAC recognize that “values change.” Traditional figures lose their authority, and divisions develop, as for example among communities and within them, this due to religious and political questions, among other things. Restorative justice, reconciliation, by whatever name it is given, seeks to rebuild the damaged social fabric and to promote community through a process. This is an important challenge, as a CORECO member observes: “constructing this network of diversity,” for this diversity “is not a challenge but rather a source of wealth.”

A growing interest in restorative justice

It is not just indigenous peoples in resistance who employ a restorative perspective in terms of justice. A growing number of countries have incorporated restorative principles into their State systems of justice, such as mediation, reconciliation, and so on. That the UN Economic and Social Council adopted a resolution in July 2002 on “basic principles on the utilization of restorative justice programs in penal settings” demonstrates the increasing interest in these ideas.

In Mexico the processes of reconciliation in terms of justice are more common among indigenous peoples (Tseltales, Nahuas, Amuzgos, Wixárikas, etc.), given that they are traditional practices. But in other countries such as Canada, Belgium, and New Zealand, the interest on the part of the official system in restorative justice is a more recent development. By introducing the restorative perspective to the penal system, there is an attempt at challenging the established system, its functioning, and its lack of efficacy. The movement is born of dissatisfaction with the lack of consideration made for victims, the penal responses (above all prison terms), and the high degree of recidivism. Today, the same countries that have imposed justice as punishment onto colonized peoples have become inspired by the practices and customs of these same communities that have struggled not to lose their traditional restorative ways. That these practices are resurging is a sign of hope. Willi Hugo Pérez reminds us that “to work for justice that heals, that restores, that transforms… it is necessary to come… with an open heart. Only in this way will we find the way to direct ourselves toward societies that are more just, more human, and more peaceful.”