ANALYSIS : Mexico – between the close and beginning of administrations

28/11/2012

ARTICLE : The 20 Years of the Diocese Coordination of Women

28/11/2012““For my daily practice, social denunciation has been a means of reaffirming myself. I have never lost the strength to continue. They have never succeeded in breaking me. They have not stolen my smile.“

On 31 October, the United Nations Committee against Torture (CAT), with headquarters in Geneva, which is an organism charged with monitoring the observance of the Convention against Torture (ratified by Mexico in 1986), opened its evaluation of the Mexican State, in the presence of a delegation of more than 30 public officials from the Mexican federal government, as well as that of some states.

In its conclusions, the CAT expressed its profound concern regarding the practice of torture in the country, particularly in light of the context of the use of armed forces within public-security tasks and the “phenomenon of aggravated impunity” in which acts of torture remain. The CAT indicates that penal reforms that have sought to change this practice by means of a transition to an oral and accusatory system has not been effective, given that security forces and the Public Ministry continue utilizing coerced declarations as evidence in penal processes.

Organizations agree: Torture is a systematic practice as a means of investigation

For months the practice of torture in Mexico has been one of the questions of concern on the part of several organizations. The National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” and the Global Organization against Torture (OMCT) presented a report regarding the Situation of Torture in Mexico (title of said report) before the CAT, an organization that in previous visits had confirmed torture to be a systematic practice in Mexico. On this occasion, despite the numerous recommendations which mechanisms for the protection of human rights have expressed in terms of the prevention, eradication, and sanctioning of torture in the country, this practice has become considerably more frequent within the context of a struggle against organized crime.

Amnesty International published its 2012 report, Known Responsible Ones, Ignored Victims: Torture and Abuses in Mexico, in which it stresses that in the last three years, “the deployment of 50,000 units of the Army and Navy to carry out police functions has contributed to this reported increase in the number of reports on torture and other abuses at the hands of soldiers.” This international organization indicates that it has not found a single sentence of condemnation for the crime of torture. “The lack of acts of accusation, prosecutions, and condemnatory sentences for torture and other abuses is a reflection of the incapacity or lack of will on the part of authorities to guarantee the effective and impartial investigation and judgment of the cases,” adds AI.

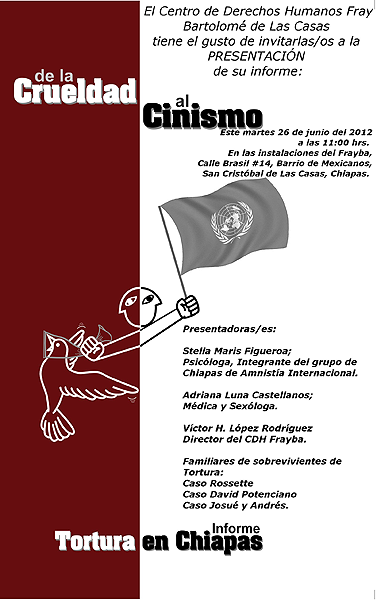

On the International Day of Support for Victims of Torture (26 June) Fray Bartolomé presented in Chiapas the Report regarding Torture in Chiapas: “From Cruelty to Cynicism,” edited by the Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC). The Center recalls in this report that in Mexico torture is a systematic and generalized mechanism of police investigation and control used by public-security agents, despite the existence of a normative opposition locally, nationally, and internationally that seeks to prevent and sanction it.

Other documents affirm the same, such as the report In Name of the “War against Crime”: A study of the Phenomenon of Torture in Mexico, carried out by Christian Action for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT-France) in collaboration with several human-rights organizations in Mexico, following an observation mission undertaken in July 2011. The majority of findings describe a recurring modus operandi. Commando-groups of several armed and masked men descend from vehicles lacking license plates. In the streets, in houses, in cars, they abuse those who are present and never are identified. They take those arrested in trucks, without indicating to them the reason for their detention. Although families report that they had believed that these occurrences were related to kidnappings for ransom-money, a common phenomenon in Mexico. When they fear that it has to do with an operation on the part of public-security forces, they present themselves at governmental offices, military bases, and prosecution centers to seek out the whereabouts of their arrested relative.

The lapse in time that occurs between the detention and presentation of the victims before the competent authority is the time in which persons find themselves most vulnerable, subjected to custody by police during the transfer to some place, often unofficial, of incarceration, and later to official detention centers. Commonly, following self-incrimination catalyzed by torture, the detained are transferred to centers of “community-control,” which continue at the federal level, though in Chiapas these were eliminated beginning in June 2011 and in Oaxaca in March 2012. The method of “community-control” introduces a regime of exception within the penal system and works against the presumption of innocence and the right to due process, as has been warned by human-rights organizations. In this way, uncertainty is maintained due to lack of knowledge regarding time of stay, to where they will be transferred, and whether someone will continue beating them. Regardless, following the elimination of “community control” in Chiapas, the CDHFBC has documented the existence of security houses, where people are detained and tortured.

According to Cecilia Santiago Vera, a psychologist who has accompanied torture cases and who has studied the impact of torture since 1995, “All the prisoners whom I have met have been tortured; some means of torture has been employed [against them], whether to incriminate them or to punish them […]. We calculate that 80-90% of those who have been incarcerated have been beaten, tortured.”

A silent practice

© Colectivo Contra la Tortura y la Impunidad

It is difficult to present statistics regarding the totality of acts of torture in Mexico, given that the majority of cases are not denounced. Beyond this, there is no national list of denunciations of torture. Furthermore, cases of torture are not said to include those classified as “injuries” or “abuses of authority,” a dynamic that makes difficult the comparison of this data at the national level. The Global Organization against Torture, within its program of Urgent Campaigns, has released 43 interventions between January 2010 and July 2012 regarding cases of torture and abuse in Mexico. For its part in the study carried out by the international group Human Rights Watch (HRW), more than 170 cases were documented between 2009 and 2011.

In general, these aggressions are implemented with certain measures whose intention is to avoid leaving signs. The systematic production of pain provokes discomfort that suggests immediate death. Generally, a repetitive cycle of pain and provocation of sensation of death is created until the survivor finally comes to accept his or her guilt, in the presence of a Public Minister or by means of signing some documents. Torture has to do particularly with the fact that the confession continues to be a key means of supporting the process of investigating a crime.

The majority of the perpetrators that the CDHFBC has identified are police officers. The act of attempting to murder another person and simultaneously avoid his or her death then becomes a social act, one that is socially accepted, thus contributing to the normalization of violence. A context then emerges in which acts of torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment have become “normal” practices, accepted by authorities involved in prosecution, the administration of justice, and the prison system, beyond being tolerated by the Executive Branch. This situation leads to the fact that the majority of denunciations presented before the Public Ministry do not proceed and/or are obstructed in their course.

During the period from January 2010 to December 2011, the CDHFBC registered 47 survivors of torture. The Center argues that “torture becomes a form of social control; regardless, despite the fears founded in the repression exercised by State forces, survivors of torture are increasingly more conscious of the importance of denunciation toward the eradication of this crime against humanity.” It indicates that when victims tell the Public Ministry or some judge that they have been subjected to torture, these officials completely ignore such denunciations, resulting in juridical irresponsibility, thus violating their obligations under the law in regard to investigating and punishing criminal activity.

Torture victims lack faith in judicial authorities and fear reprisals when they do make denunciations, especially when they are arrested and such conditions are joined by death-threats against their persons. Josué and Andrés López Hernández, from the Tsotsil indigenous community of Pueblo Nuevo Solistahucán in Chiapas, decided to present a denunciation for the torture to which they were subjected in January 2011. Shortly thereafter, the two brothers were transferred to another part of Chiapas, very far from their home. Andrés’s wife testifies that “We cannot go regularly to visit him, because he is very far away, some 8 or 9 hours. We [mother, wives, sisters] go once a month, when we have money to do so.”

In 2003 Mexico put together and published a manual for the application of a specialized medical/psychological dictamen for cases of possible torture and/or abuse, a document based on the Istanbul Protocol (a manual approved by the United Nations in 1999 that presents a number of indications at the international level to determine if someone has been tortured). The first obstacle to overcome consists in having agents from the Public Ministry accept the task of receiving and registering denunciations of torture, given that it is public officials who are generally denounced as perpetrators of this crime. Sometimes, before a judge, such officials seek to reclassify the events as crimes of minor gravity (abuse of authority, injury, etc.) that carry with them shorter terms of punishment.

The most oppressed: The poor, indigenous peoples, and social movements

A person, especially if he or she is neither influential nor wealthy, and even without any prior criminal record, can be arrested, tortured, and imprisoned without having the chance to defend him- or herself or asserting his or her rights. It is enough that s/he find him- or herself in an inappropriate place or at an inauspicious time, when another person accuse him or her, generally under pain of torture, or that discrepancies be presented with an individual who enjoys a certain power. In its report, ACAT-France makes reference to the Mexican situation whereby there is seen the “criminalization of poverty,” by which the risks of arbitrary arrest, torture, and abuses rise significantly. The presence of translators is not always assured; an indigenous prisoner is thus seen as more easily obligated to sign a declaration without understanding it, or on the contrary see him- or herself as facing serious obstacles to present a denunciation.

David Potenciano Torres was detained in May 2011 in Palenque, Chiapas, by elements of the Specialized Prosecutorial Office against Organized Crime (FECDO), who harassed him in his apartment and placed a t-shirt in his mouth and poured water into his nose, while they accused him of having murdered a cattle-rancher named Pedro Fonz Ramos. On 28 December 2011, David Potenciano was released, under the juridical figure of abandonment of penal action, as promoted by the State Attorney General’s Office, in a public media act with the presence of Chiapas state governor Juan Sabines Guerrero. David Potenciano was never given an explanation regarding the arbitrary detention and torture to which he was subjected.

Cecilia Santiago expresses that, “For me, it is a strategy: the use of torture to imprison and then justify that there exists organized crime, and for that reason we need more army [presence] and to receive more aid from the United States, and so control the streets.” Torture becomes a method of repression exercised against social movements considered to be threatening, and thus it becomes a means of silencing social protest.

In Oaxaca, the trade-unionist Marcelino Coache was arrested and tortured for the first time in December 2006 during the repression of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO). In 2009, he was newly arrested in secret and violently tortured thereafter; he was left strewn on the street, abandoned. Between 2008 and 2011, he presented 11 denunciations for torture, death-threats by telephone, robbery, and injury; even his family members have received a number of death-threats. To date there has been no resolution of his denunciations.

The family of Margarita Martínez Martínez and Adolfo Guzmán decided to flee from the state of Chiapas, given that they had received numerous death-threats, after having denounced that they were being harassed at their home in Comitán de Domínguez in November 2009. After this denunciation, Margarita Martínez suffered a kidnapping and sexual torture in February 2012, as well as harassment and death-threats in November 2010. For this reason, the family has been awarded precautionary measures by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

In the case of the ecologist campesinos Rodolfo Montiel Flores and Teodoro Cabrera García, defenders of the forests of the Sierra de Petatlán in the state of Guerrero, the Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACHR) has demanded the exclusion of evidence obtained using torture. It affirms that the declarations obtained via coercion cannot be considered true, given that the person under torture attempts to produce the necessary information to put an end to cruel treatment or torture. In this way, it established that, as in the case of Montiel and Cabrera, the fact that a confession was made before an authority does not automatically mean said confession is real, given that this confession could be the result of prior mistreatment suffered by the person in question, or fear that this type of behavior recur afterwards. It must be added that Guerrero is the only state that lacks a special law as regards torture, and torture is not classified as a crime in the Penal Code in this state.

Sexual torture

It is important to mention that in the cases of torture committed against women, the means that are utilized carry sexual connotations. Sexual violence is one of the privileged means used by perpetrators to morally degrade women, humiliate them, and apply special punishment according to gender. It is not a matter of isolated, individual cases, but rather has to do with structural considerations.

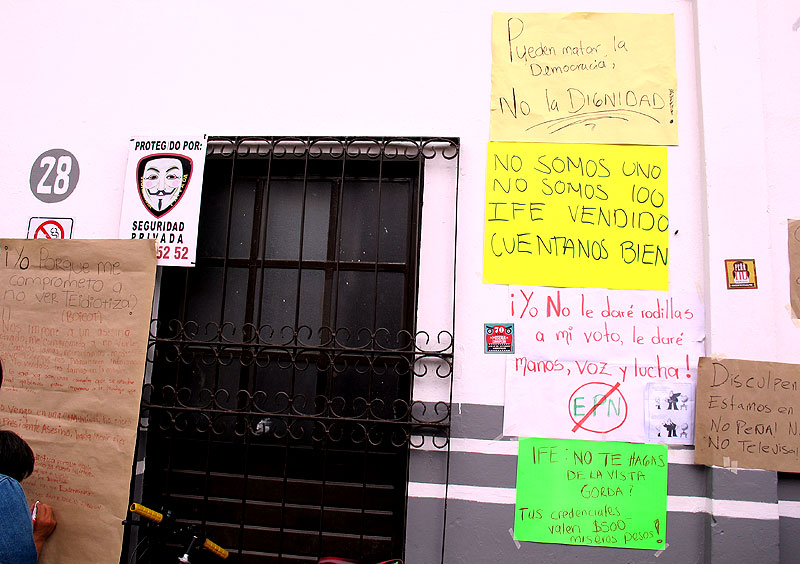

Italia Méndez Moreno, one of the 27 women who denounced having been raped following the police operation that took place on 3 and 4 May 2006 as carried out in San Salvador Atenco, expressed that “It did not have to do with rape. If the same had happened at work, at a party, or at school, and if some bastards had put me in a car, they would do the same that they did to me in Atenco. I believe it was rape, but it cannot have the same treatment or discourse when it is elements of the State who do this during an act in which all the political forces of this country participated, after which the entire world was silent. This is part of the violence of the State: this is torture.” Suhelen Cuevas, another of the women who form part of the photographic project Mirada Sostenida (Sustained Look), which examines the survivors of sexual violence at Atenco, declared that “The humiliation that the police subjected us to sought to make us women believe that we were nothing, that we had no reason to be at the protest.”

The objective of obtaining self-incriminating confessions

To date, the Mexican State has presented four periodical reports to the CAT, from 1988 to 2004. Despite the fact that the Mexican Republic has introduced “constitutional reforms into the system of penal justice,” the law on motions, the introduction of protocols regarding the use of force, and “the implementation of the Istanbul Protocol,” as a governmental document claims with regard to the use of torture in the country, the CAT concluded that the penal reform that seeks to change this practice by means of a transition to an oral and accusatory system has not been effective, given that security forces and the Public Ministry continue to use declarations extracted under coercion as evidence in legal proceedings. Both the CAT and the organizations that have presented reports on torture in Mexico affirm that it is the deficient system of investigation that upholds the practice of torture, given that there must exist self-proclaimed guilty parties to indict the guilty.