ANALYSIS: Mexico – Expansion of social mobilizations with no response from authorities

26/11/2013

ARTICLE: Serious Damage due to Storms in Guerrero – Two Months on, the Mountain Region is far from returning to Normality

26/11/2013As a number of reports have illustrated in recent months, the situation of violence against women in Mexico is far from being resolved. These reports speak to the multiple forms of violence, both direct and physical as well as structural and cultural. According to a study undertaken by the Inicia A.C. organization in 2010, violence is a form of exercise of power and domination by means of the employment of force (physical, psychological, economic, political), and it implies the existence of inegalitarian relationships between those exercising and receiving the violence. The study specifically mentions violence against young women in indigenous communities, settings where such violence takes place within the family and community. The report notes that violence is perpetrated and tolerated by the State as well.

Clearly, gender-based violence is in no way limited to indigenous communities. Mexican society is highly patriarchal and, for this reason, men and masculinity are valued more than women and femininity. This sexist patriarchal system finds itself reflected in all aspects of daily life and in all classes of society, rich and poor, indigenous and mestizo, and urban and rural zones. As Margaret Bullen and Carmen Diez Mintegui write in a 2012 essay on femicide: “girls and women killed in Mexico are of different ages […] they pertain to all social levels and socioeconomic strata, and although the majority are poor or marginalized, some were rich, from the upper class and elites.” The document stresses that “femicide flourishes under the hegemony of a patriarchal culture which legitimizes despotism, authoritarianism, and cruel, sexist treatment—patriarchal, misogynist, homophobic, and lesbophobic—as supported by classism, racism, xenophobia, and other forms of discrimination.” The ubiquity of violence against women in Mexican society leads to its normalization among the general public.

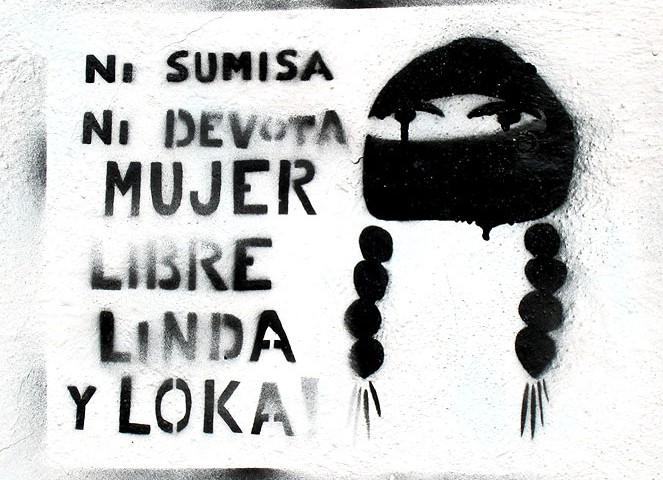

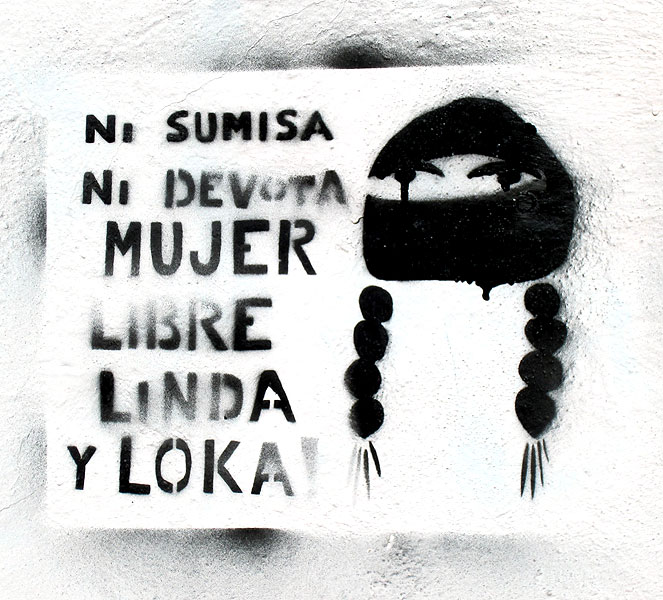

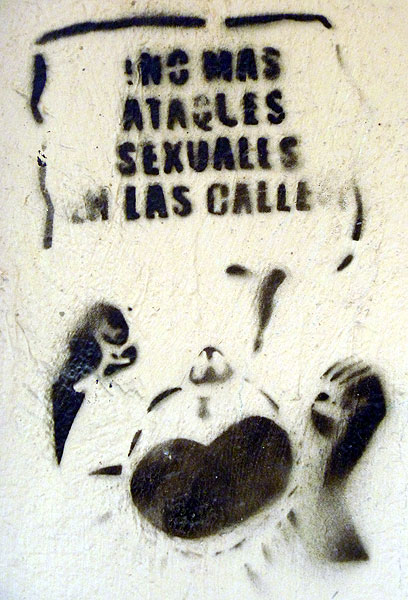

Manifestations of “everyday” violence

The forms in which violence is manifested runs the gamut from selective abortion in favor of males to forced pregnancy, differential access to nutrition and education, sexual abuse, rape, and partner abuse. Regardless, according to a study carried out by Mercedes Olivera in communities in Chiapas in 2011, indigenous women often consider it to be violence only when there are beatings. Psychological violence such as scolding and jealousy are minimized. The interviewers for this study noted that many women did not dare to say that their husbands beat them, since he was often present during the interviews. Upon analyzing the data with the participating women, they agreed that in fact there is almost no woman who has not been beaten by her husband, and that the situation has not improved.

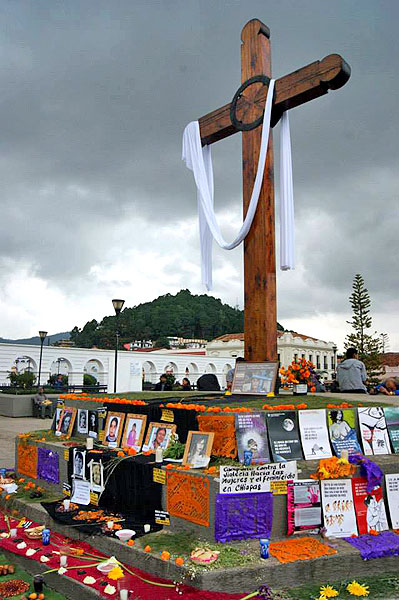

© Campaign Against Violence Against Women and Femicide in Chiapas

According to the study, with regard to young indigenous women, there exist national and international laws which frames violence against them not only as a penal or social question, but indeed an issue of human rights violation. However, the problem is more complex, given that indigenous women suffer violence and discrimination not only for being women but also being indigenous. For this reason, violence against them represents an attack on their individual and collective rights. Furthermore, violence also takes place by means of omission, impunity, injustice, repression, and discrimination.

Another study from Inicia A.C. conducted in 2011 mentions the lack of freedom for young indigenous women in states such as Oaxaca and Chiapas in terms of marriage. It argues that they suffer from male-centered elements—hardly limited to indigenous cultures—which are expressed in the idea of “taking care of,” given that young women are often objectified and seen as the property or under the tutelage of men, whether father, husband, or brother. In an extreme case, women mentioned that in the community of San Jorge Nuchita, Oaxaca, the husband brings cash to the father of the girl, expressed as a “purchase of the woman.” Women in the study mentioned that “because they bought them, men think that women belong to them like things, and for this reason they beat us like animals.” In the highland region of Chiapas, it is only when grave problems exist among married couples or when a relapse occurs that separation is accepted, and when it is finalized, the woman’s family is obligated to return to the man’s family the cash and gifts they received when he asked for her hand in marriage.

The 2011 Inicia AC study also mentions the difficulties that indigenous women face in terms of obtaining “permission” for example to go out into the streets or study somewhere else. If young women go out unaccompanied, they are characterized as “wild” or “easy” because there is concern over their honor, principally in sexual terms. The report emphasizes also that, in each of the five regions under study,(1) there were cases of women who were verbally or physically abused in their communities: insulted, accosted by men on pathways, and even assaulted during dances for community celebrations. In the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, all the young women said they knew some teacher who had assaulted students at school.

The Oportunidades Program: an example of structural violence

Several persons and organizations have come to consider the Oportunidades (Opportunities) program as a form of structural violence imposed by the federal government against the female population due to the conditions mandated by the program. The program’s conditionality generates a certain level of dependence and passivity among beneficiaries. According to Mercedes Olivera’s study from 2011, more than 95% of the marginalized families of Chiapas receive income from Oportunidades. The money that mothers receive for each child to attend primary or secondary school represents an important aid and means of “security” for poor families and their everyday survival. In the highlands region, 46% of the families consider Oportunidades to be the main source of income, second only to those who obtained most income from wages of husbands or partners (48%). One woman from the Chilón municipality mentioned that “the only thing that gives us enough to eat is Oportunidades; the land has been exhausted, it doesn’t give anything anymore, and there’s no work. Now I maintain my family from what the government provides through Oportunidades.”

The researchers consider the money which beneficiaries receive for each child to have a patriarchal character that creates dependency, as mothers must accept the imposed conditions to continue as beneficiary. Some of these conditions include going regularly to medical visits they view as unnecessary and undesirable, as well as to attend obligatory monthly or bimonthly trainings having to do with personal hygiene and health. The trainings take place at rigid times that do not take into account women’s availability, and they threaten to cut off support if the women do not attend. A woman from San Cristóbal who was interviewed during the study said that “now I am like a prostitute of the government, because in exchange for giving me money I have to let doctors put their hands in my body.” If beneficiaries fail to present themselves to these medical appointments, part of their Oportunidades assistance is cut.

Recently, the Chiapas state government has added two conditions to the Oportunidades program. For one, women who receive the program must take classes to read and write Spanish, something that is difficult for many indigenous women who speak only one language and especially for those who are elderly. Another recently added condition obligates women to spend 200 of the total 850 pesos provided by Oportunidades on certain predefined consumer products sold in government stores; if they refuse, they are threatened with losing all support. The obligatory consumption, according to women from indigenous communities in northern Chiapas interviewed by SIPAZ, are products that are not very useful to them, such as Maseca brand corn flour when corn (maize) is readily available in communities, or canned goods which they are not accustomed to consuming. Furthermore, women in interviews mentioned that the obligatory goods are more expensive than the equivalents which could be attained at a local store in the community itself. Residents of communities of the Lacandon Jungle mentioned similar criticisms during a SIPAZ visit to the region at the beginning of November. Mercedes Olivera’s 2011 study concludes that the Oportunidades program reproduces dependence and servility among women who, for the benefit of neoliberal capitalism, are depoliticized and subordinated to conditions of modern enslavement.

Violence against women in Mexico examined by the (inter)national community

© Campaign Against Violence Against Women and Femicide in Chiapas

In recent months, several national and international organizations have published reports having to do with the growing situation of violence against women and femicides in different parts of Mexico. On 23 October, for example, to mark the second evaluation of the UN Universal Periodic Review (UPR), Mexico received 176 recommendations from member states of the Human Rights Council, 33 of which focused on the human rights of women. In a shadow report made by the Equis-Justice for Women organization, there is mention that between 2007 and 2010 the states of the Mexican Republic included in their normative legislation specific measures to protect the rights of women to enjoy lives free of violence. Likewise, states strengthened the penal codes to recognize various forms of violence against women and/or to specify certain types which already exist. Regardless, the “broadness of the definition regarding the types and modalities of violence included in the laws for access to a life free of violence is not entirely reflected in the legal code, due to the fact that there are discrepancies between the penal codes and these new laws.” The report notes that “of the 240 sentences analyzed in 15 Superior Tribunals of Justice, only four sentences mentioned the General Laws on Access of Women to a Life Free of Violence (1.66%). Thus there exists a large gap in the implementation of these laws on the part of the justice system.”

Also in terms of the UPR, Amnesty International (AI) recommended that the Mexican State give priority to measures to prevent and punish violence against women in the 31 states of Mexico, “especially those that have an elevated number of denunciations of murders and attacks against women and girls, especially Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Mexico State, and Oaxaca.” In accordance with the National Citizens’ Observatory on Femicide, the entities wherein discrimination and femicide would justify the declaration of a gender alert include Chiapas, Sinaloa, Mexico State, Veracruz, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, Durango, Sonora, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Guanajuato, and Morelos. In some of these states, civil organizations have requested gender violence alerts through the National System to Prevent, Attend to, Sanction, and Eradicate Violence against Women, though not one has been accepted in the five years of the existence of this institution.

At the beginning of November, Nobel Prize winners Jody William and Rigoberta Menchú presented a report on violence against women in Mexico. The study, entitled “From Survivors to Defenders: Women who Confront Violence in Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala,” warns that the problem of femicide and violation of human rights in Mexico has reached “crisis” levels. It notes that in Mexico 6.4 women are killed every day, with 95% of these murders going unpunished, according to data from the report and the United Nations. The study was presented by the Association for Justice (JASS), the Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights, and the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity.

“In Mexico they forget to punish those responsible”

The question of femicide is receiving attention both on the part of civil society as well as the international community, which is engaged in a campaign to influence Mexican authorities. On 5 November, the embassy of the Netherlands in Mexico City organized a lunch to commemorate Hester van Nierop, a young Dutch woman who was killed in Ciudad Juárez in 1998. The victim was found under a bed with signs of torture and sexual abuse. The goal of the event was to bring together different parts of Mexican and international society, such as government, victims, and non-governmental organizations, to discuss actions that could be taken to improve public policy with regard to femicide. In an interview, Arsene van Nierop, the mother of Hester, said that “femicide is not something limited just to Juárez or México; instead it is found throughout the world. The problem in Mexico is that they forget to punish those responsible […]. I will continue to struggle. The question is not of a murder, but rather of impunity.”

Data from the Citizens’ National Observatory on Femicide show that violence against women in Mexico increased 125% during 2013, particularly gender-based homicides against girls and young women. “The crime of femicide still has not been recognized by all Mexican states,” notes the Center for Women’s Human Rights (CEDEHM). Femicides many times are accompanied by sexual violence and torture. Impunity for femicides is higher in comparison with other crimes, due to discrimination. At the 5 November meeting at the Dutch embassy, Mexico was urged to investigate and punish attacks against women from a gender perspective, as well as to protect human rights defenders more effectively. Furthermore, the need was stressed to create Women’s Justice Centers, and to employ effectively the protection mechanisms already established by Mexican law. According to the Citizens’ National Observatory on Femicide, 10 states face situations in which murders against women have been on the rise, including Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

Women rising up against violence

In August in Guadalajara, about 1,600 women met to celebrate the IX National Feminist Meeting, toward the end of discussing how to convert Mexican feminism into a true interlocutor in the State’s decisions in order to contribute to the reduction of violence against women. According to the denunciations, this type of violence takes the lives of over 1,800 women yearly, inhibits the exercise of the human rights of the indigenous and campesinas, has reduced the wages of more than 16 million female workers, and has restricted the right to legal abortion in 18 states. The feminists agreed on a collective agenda focusing on four aspects: rejection of all forms of violence against women, advocacy of sexual and reproductive rights, advocacy of the right to decide on one’s body, and the right not to be discriminated against for one’s gender and sexual orientation.

At the state level women have also been making efforts to bring attention to the exceedingly high levels of violence and femicide. On 1 and 2 November the Day of the Dead was celebrated in Mexico, a time when families recall the dead by erecting altars in homes and spending the days visiting the cemeteries with the favorite foods and drinks of the deceased relatives. In several parts of the country these dates are taken as an opportunity to call attention to the alarming numbers of women who have been murdered in recent years. In Chiapas, for example, activists and different organizations that form part of the “Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Femicide in Chiapas” organized several activities and made an offering in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. They installed an altar where they placed white crosses made of cardboard to denounce the violent deaths and femicides of more than 80 women in the state so far this year. According to statistics, this situation makes Chiapas the fifth-highest state of Mexico in terms of number of femicides. Around 20 civil and women’s groups have joined the campaign in San Cristóbal de las Casas; their objective, among others, is to inform and sensitize the public with regard to the origins and risks of this type of violence, as well as to promote change in terms of gender relations.

Also on the Day of the Dead, in Oaxaca City there was an offering of breads, fruits, flowers, liquor, and candles at an altar to commemorate the murdered women of Oaxaca and throughout the country. Activists organized an offering for the victims of violence, “recalling their names, their ages, their occupations, what happened to them, who their attacker was, and what the status is of their legal process,” as the Group on Femicides of the Republic explained. Some weeks earlier, in observance of actions taken against femicidal violence, dozens of women marched through the center of the city, in the first public activity carried out by the “Radical Antipatriarchal Action” collective. Members of the collective noted that “[s]olely through our own efforts will we be able to create change, only by going out and raising our voices will we be heard.”

… … …

- The study took place in the northern sierra of Puebla and Totonacapan, in the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, and in three regions of Chiapas (the highlands, the Lacandon Jungle, and the border region). (^^^)