I n January, the report “Voting Under Fire: Understanding Political-Criminal Violence in Mexico” was presented, which documents that in 2023 there were 574 incidents of political-criminal violence.

264 of them were against public officials or candidates for elected office, says Data Civica, the consulting firm behind the report. 91 occurred in Guerrero, 64 in Guanajuato, 43 in Zacatecas, 42 in Veracruz, and 38 in Michoacán and Chiapas each. In December alone, 42 events associated with political-criminal violence occurred, including attacks, kidnappings, armed attacks or murders. According to the consulting firm, from 2018 to 2023, there have been 1,610 attacks, murders and threats against people associated with the political or government sphere or against government or party facilities. In that period, 105 candidates, aspiring and former candidates were murdered.

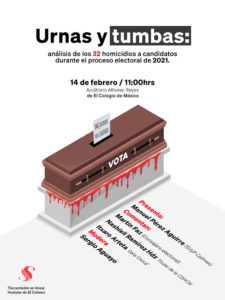

In February, the Colegio de Mexico presented the investigation “Ballot Boxes and Graves”, in which it analyzes electoral violence and the reasons behind the 32 murders of candidates for popularly elected positions in the 2021 elections. In the main characteristics of these cases, the investigation details that “lethal electoral violence is eminently local, because 85 percent of the 32 victims were competing for municipal positions. (…) These attacks are normally against opponents of the current mayor, as occurred in 25 of the 32 cases.” Strikingly, only 11 of 32 homicides can be clearly attributed to criminal organizations that “have effectively limited Mexican democracy, having the ability to decide who has the right to compete and who does not. (…) Not only are the parties not up to the challenge, but they themselves are resolving the struggle for power with bullets. In other words, they have not only let criminal organizations fill power vacuums, especially local ones, but they are replicating their techniques to resolve the fight for public power,” the investigation emphasizes.

“Such high levels of violence are clouding the quality of democracy and governance in the country. In particular, electoral violence, that intentionally implemented by perpetrators to modify both the results and the electoral processes, distorts the virtues of a democratic regime. (…) If we take into account that one of the greatest achievements of the Mexican transition to democracy was its peaceful nature, the growing electoral violence is increasingly disturbing,” the investigation warned when raising strong concerns about the 2024 elections.

“Alarming crisis regarding human rights”

In November, more than 300 national and international organizations issued 18 reports with recommendations to reverse the “alarming human rights crisis” in Mexico, which “has deepened” since 2018, when President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) took office. They denounced the closure of civic space in the country, militarization, widespread violence and impunity, structural poverty, espionage, disappearances, extrajudicial executions, among other serious violations, in the context of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the Mexican State.

When this review was carried out in January, Mexico received more than 300 recommendations to improve the human rights situation in the country. The main ones revolved around violence against women, journalists, human rights defenders, children, adolescents and youth, as well as disappearances, and the management of the migration crisis, among other topics. Likewise, the issue of militarization in the country and its impacts on respect for human rights was questioned. For the first time, Mexico received specific recommendations to ensure that public security is civil. It is important to emphasize, however, that all these recommendations are not binding. Mexico will have until June to respond to them and decide whether to accept them.

Regarding the vulnerability of human rights defenders, in January, the non-governmental organization Cerezo Committee Mexico reported that, during the year 2023, 14 extrajudicial executions against human rights defenders were recorded in Mexico, 11 of them in Oaxaca. There are 93 cases so far in the current government. The reasons for which the executed human rights defenders fought were mainly for the right to territory, for a decent life, decent housing, and for the self-determination of indigenous peoples. Of the victims, only one did not belong to an indigenous group. “The difference from previous reports is that we only found two cases in which the beneficiary was the Federal Government, in this report there are four cases,” said the Cerezo Committee.

As regards freedom of expression, in January, Article 19 warned that 2024 will be an “extremely violent” year for the press due to political disputes linked to the electoral context. Despite the drop in murders of journalists in 2023 (five compared to 13 the previous year), it pointed out that, in the last year, there has been an intensification of the stigmatization of and discrediting campaigns against communicators by local political actors, who have replicated AMLO’s “virulent” discourse against the press. “There is actually a political class that is extremely intolerant of criticism and what the president has done is provoke that intolerance,” it explained.

In January, several civil society and journalistic spaces denounced the violation of privacy and vulnerability implied by the leak of personal data of more than 300 journalists who have covered AMLO’s morning press conferences. The Civil Society Organizations Space (Espacio OSC) warned about the fact that what happened implies “significant risks that can have various consequences. These include damage to reputation, financial losses, acts of discrimination, profiling by alleged aggressors, as well as attacks on their homes or routes, among other serious implications. This is especially relevant when considering that Mexico is positioned as one of the most dangerous countries for the press, with 163 journalists murdered and 32 missing.”

Another crisis, migration

In December, the Mexican Refugee Aid Commission (COMAR) reported that asylum requests broke a new record in Mexico with 136,934 requests. It is worth remembering that in 2013 only 1,296 requests were counted and since 2018 they have increased year by year. Chiapas is where more than 60% of the applications are registered and it is important to emphasize that asylum seekers must remain in the federal entity where they began their process. At the same time, the acceptance rate has been reducing, mainly affecting people from Haiti, with only 13% of applicants admitted to the country in 2022. It is worrying that a quarter of the registered applications are from minors, warned the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), a figure that exacerbates the humanitarian challenge on the country’s southern border. These children and adolescents mostly flee due to violence, persecution and armed conflicts, according to UNHCR.

In January, Human Rights Watch (HRW) called on Mexico to reject an agreement with the United States that could restrict the right to asylum and increase summary deportations. According to analysts, Republicans, who have a majority in the House of Representatives, have conditioned the approval of a $106 billion military aid package for Ukraine and Israel in exchange for new anti-migrant measures, including closures of part of the border, further limit asylum applications and increase mass deportations. These migration measures “would contravene international human rights standards and expose thousands of people and asylum seekers to dangerous situations,” HRW warned. Currently, nearly 10,000 people are arrested a day at the border between the United States and Mexico as the Biden administration is adapting the Republican Party’s xenophobic anti-immigration discursive framework ahead of the 2024 elections, according to the research center Feminisms and Democracies.

Likewise, in January, the Southern Border Monitoring Collective demanded the “immediate and definitive closure” of the immigration stations, after the death of Jean “N”, of Haitian nationality, who died at the Siglo XXI immigration center, in Tapachula, Chiapas. It stated that this case is not isolated, but rather joins a long list of migrants who have died inside Mexican immigration centers. It stated that they have documented that in these spaces migrants are subjected “to conditions of overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, lack of medical services, poor nutrition, physical and psychological abuse, and sexual abuse, which together constitute torturous environments.” It also reported “cases of riots, protests, self-harm and suicides,” which show “the degree of desperation and suffering experienced by people in immigration detention.” It denounced that the Mexican State intends to hide, and even deny, the reality of these centers.

CHIAPAS – Civilians “human shield” in the dispute between groups linked to organized crime

In December, the Diocese of San Cristobal in its statement titled “A Cry for Peace Silenced by Weapons,” noted that “in the state of Chiapas we are living in the midst of criminal groups that dispute the territory, putting civil society as a human shield in said dispute, without enforcing the right of the people to security, free transit, peace and others.” The area most affected by this situation has been the Border.

In November, it was announced that thousands of residents of the municipality of Maravilla Tenejapa were forcibly displaced after organized crime groups invaded the region and kidnapped the municipal president, Zoel Lopez Gutierrez, and one of his colleagues. The upsurge in violence in this region in recent months was attributed to the battle between two organized crime organizations that seek to control border territories that are strategic for their businesses.

In January, residents of the municipality of Chicomuselo, in the Sierra de Chiapas, denounced “the increase in violence that is occurring without, to date, a response from the state.” They pointed out a confrontation that occurred on January 4th between two organized crime groups in the Nueva Morelia ejido, belonging to the same municipality, which reportedly left at least 20 people dead, including two civilian residents who fell in the crossfire. The “Civil Society of the People of Chicomuselo” affirms that “we have seen hundreds of families leave Nueva Morelia and neighboring communities for fear that confrontations will continue, since in this area there are large interests such as mining and control of the border,” they stressed. They questioned: “why don’t the army, the national guard and the state police act? What are you waiting for to dismantle and disarm these criminal groups that are using people as a human shield?”

Dozens of families continued to leave their homes in the municipalities of Chicomuselo, La Concordia and Socoltenango in subsequent weeks. The state Civil Protection Secretariat reported that it provides humanitarian aid to displaced residents, although it did not recognize this status, but rather considers them as “people in a vulnerable situation.” AMLO asked the residents of these communities to stay in their places of origin and to place their confidence in the National Guard to confront crime groups. He declared that “the National Guard is to protect the people, it is not infiltrated by crime, they should be trusted. And if they do not want the Guard to be there, it is because they are protecting criminals.” The Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba) estimates that at least 2,300 people have been forcibly displaced from more than 30 communities in this episode.

In January, called on by the Believing People (Pueblo Creyente), thousands of parishioners from the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas made a pilgrimage to San Cristobal, a setting in which they denounced drug violence and other forms of injustice they experience. The auxiliary bishop, Luis Manuel Lopez Alfaro, stressed that the construction of peace is “an urgent task in the face of the shadow of death that is covering our state of Chiapas, and that in recent days has become darker along the entire border with Guatemala”. “This darkness has been generated by criminal groups that fight to see who will control the border with Central America, in their fight they have passed over the communities; they have forced them to align themselves with them or have to leave their place, losing everything they have worked for during their lives. (…) this has brought pain, suffering, extortion, death, missing persons, displaced communities, communities without free movement, decimated communities.” Referring to the response from the authorities, he said that “it is not possible to continue denying reality and say that nothing is happening in Chiapas, everything is happening here and we cannot remain silent or be indifferent in the face of so much pain, frustration, helplessness when we see ourselves invaded and governed by those who use weapons and violence. We see the increase in militarization, but we do not see results.”

EZLN: 30 years after the armed uprising

The 30th anniversary of the uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) was celebrated from December 30th to January 2nd at the caracol “Resistencia y Rebeldía: A Nuevo Horizonte” in Dolores Hidalgo, municipality of Ocosingo. Thousands of attendees, including groups and organizations, both national and international, media, militia and support bases, participated in the celebration in which cultural days were held through which they recreated the history of their autonomy, the violence of the current context and criticism of the system and “bad government” (see Article).

In January, more than 40 members of the Ocosingo Regional Coffee Growers Organization (ORCAO) forcibly displaced 28 Support Bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN) in the La Resistencia community, Moises y Gandhi region, municipality of Ocosingo. They destroyed the Autonomous Primary School, burned homes, stole property and stripped the community of animals, tools and food. In February, members of ORCAO attacked the Moises y Gandhi community again. According to the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” (Red TDT), they fired a series of approximately 100 shots with heavy-caliber weapons. Red TDT asked that “respect for the territory of the BAEZLN, its free determination and autonomy, as well as a life free of violence be guaranteed. An immediate and diligent investigation be carried out to generate a route where ending this climate of violence is prioritized.”

OAXACA – “Between the PRI and MORENA: Setbacks, Impunity and Simulation”

In December, a group of civil organizations, defenders and journalists presented shadow report in Oaxaca prepared within the framework of the UPR about the human rights situation in the state. This report covers the period 2018-2023 and was titled “Between the PRI and MORENA: Setbacks, Impunity and Simulation.” “Despite the fact that there was a political alternation at the federal and state level between the PRI and MORENA, in Oaxaca the violations of human rights have deepened, coupled with the fact that setbacks, simulation, omission, negligence, corruption and lack of autonomy of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers,” the organizations stated. They also stated that “the lack of political will has been the main obstacle to facing the serious situation that the state is going through. ‘Peace’ is just a government narrative and part of the simulation.”

The last few months have been marked by cases of criminalization and persecution of human rights defenders, mainly in the Tehuantepec Isthmus. In January, a group of citizens and community members made up of the Mixtequillense Civil Resistance installed a two-day road block on the La Ventosa-Mixtequilla highway to demand information and transparency regarding the industrial park called “Polo de Bienestar” that the federal government intends to install. in the municipality of Mixtequilla. After an assembly agreement, residents of Santa María Mixtequilla also expelled elements of the Navy Secretariat from their lands and burned the camp of the Tehuantepec Isthmus Interoceanic Corridor for not having been informed of the damage that the project may cause. Subsequently, a police operation was carried out made up of elements of the National Guard and the ministerial police that sought to comply with ten searches and nine arrest warrants for the alleged theft of a municipal patrol car. Relatives of the detainees (seven men and two women) reported that the arrests were violent, including the use of sexual violence and threats inside the homes.

In February, David Hernandez Salazar was sentenced to 46 years and six months in prison, a fine of $182,818 and a payment for damages in the amount of $1,000,001,500, for opposing the construction of an industrial park in the Interoceanic Corridor. The indigenous Binniza defender has been criminalized since 2017 for his fight to defend the Pitayal Common Use Lands, Puente Madera, for which he faces three judicial proceedings. Social organizations from the Tehuantepec Isthmus repudiated the sentence and demanded its revocation when “these sanctions are a clear example of criminalization and persecution for his work as Defender of Territory, Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples.”

Gender violence is another constant concern. In February, 13 cases of murders of women were recorded since the beginning of the year. This brings the total to 122 crimes against women in the administration of Governor Salomon Jara. The Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP) notifies that, in 2023, 38 investigations were initiated for the crime of femicide in Oaxaca, which places the state in sixth place nationally last year. For its part, GES Mujer recorded 95 violent deaths of women in 2023, most of these occurring in the Isthmus and the Mixteca.

GUERRERO – “The Truth Dressed in Olive Green”

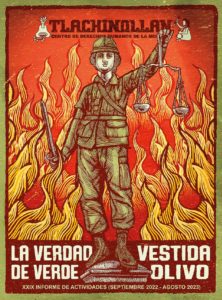

In January, La Montaña Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center presented its XXIX report titled “The Truth Dressed in Olive Green,” in which it stressed that “at this end of the six-year term, the President of the Republic, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, positioned the Army as the main security body that has a legal framework, contrary to international recommendations. It has a large federal budget and enjoys multiple prerogatives with the new functions assigned to it by presidential decree. The armed institute is the Secretariat that has the greatest recognition, support and protection from the President of the Republic, to the extent that he has become its spokesperson and defender at all costs. He insists on exonerating them of crimes against humanity and at all times separates them from their involvement in the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students.”

On another note, Tlachinollan stressed that “the authorities of Guerrero have succumbed to organized crime. Although Governor Evelyn Salgado Pinda has the full support of the President of the Republic, there are no tangible results, two years into her administration. The presence of the National Guard is far from being a shield for the population that is defenseless in the face of the growing power of criminal groups. Violence has broken out in the main tourist cities and in Chilpancingo. In the eight regions, extremely serious cases have been recorded that show the weaknesses of a security model designed by military commanders who have subordinated civil authorities.” Given this, “the aggrieved population has been left on the sidelines, the victims are mocked and the families’ cry for justice is not heard. There is a distancing between the state authorities and the multiplicity of civil society players who do not find an effective dialogue to present their demands and proposals.”

Another aspect of concern addressed by the report has to do with the fact that “governments, instead of triggering development with the participation of communities that have known how to care for and respect nature, have implemented an extractivist model based on the predatory exploitation of forests, in the plundering of natural wealth, the destruction of habitat with open-pit mining and the decapitalization of the countryside.”

In this framework, the vulnerable situation of human rights defenders and communicators continues to be critical. In November, armed men shot four reporters in Chilpancingo. Three were injured. The previous week, criminals kidnapped three journalists in Taxco, as well as their relatives. After a few days they were released, but they kept the son of one of them captive. “Violence against journalists has increased exponentially during the electoral period,” stated Article 19. It urged the authorities to combat impunity: “It is impossible to maintain protection mechanisms for journalists in perpetuity while investigations into threats and attacks do not advance, an effective strategy is necessary that gives results and deters the perpetrators of threats and crimes against the press.” In February, searcher Noe Sandoval Adame, a member of the María Herrera Family Search Collective, was shot to death in Zumpango, who was searching for his son Kevin Sandoval Mesa, 16, who disappeared on November 17th, 2023. The crime was condemned by groups and organizations that constitute the National Search Brigade who demanded investigation and justice for Noe and his family.