SIPAZ ACTIVITIES (From mid-May to mid-August 2015)

06/09/2015

FOCUS: SIPAZ 20 years accompanying Lights of Hope

21/03/2016“There is a wide national, regional and international consensus about the garvity of the current human rights situation in Mexico.”

In March of 2015, the report of the United Nations Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment of the High Commission noted the generalized character of torture and impunity had been seriously questioned by Mexican diplomacy. The second semester of 2015 was equally marked by reports and declarations which were critical of the different high level instances regarding the human rights situation in the country.

In October, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR) presented the preliminary conclusions of their “in loco” visit. It noted “the grave human rights crisis that Mexico is experiencing, characterized by an extreme situation of insecurity and violence.” The sub-secretary of the Secretariat of Governance for Human Rights, Roberto Campa Cifrian, considered that this report “does not reflect the reality of the country” as it was the product of “meetings and interviews” in “only six of the 32 entities (…) carried out in the space of five days.” NGOs condemned the response, considering it a disqualification of the international organizations that document the reality of the country.

Shortly after, during his visit to the country, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad El Hussein, expressed the urgency to combat impunity given “the gravity of the current situation of human rights in Mexico.” With the intolerance of the government towards international criticism, he recommended “not to shoot the messenger but to pay attention to the message.”

Equally in October, for the first time since 2008 when the Merida Initiative was launched (US funds destined to Mexico to combat organized crime), the State Department cut the aid by 5 million dollars of the 148 million that it was planned to give. This decision was welcomed by human rights organizations in the United States and Mexico.

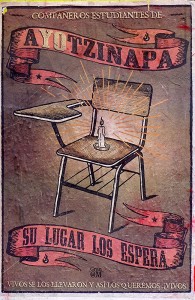

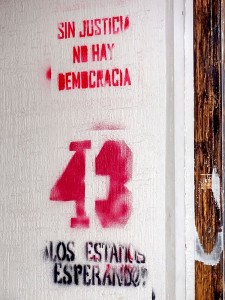

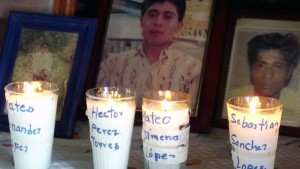

Later, in the framework of the 156th period of sittings of the IACHR, one of the main achievements was that the Mexican government agreed to extend the presence of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (IGIE) by by six months. This group was formed to investigate the forced disappearance of 43 students form the Normal Rural School at Ayotzinapa in Iguala, Guerrero, in September of 2014. The decision to extend the work seemed to mark a change in the Mexican government. Through it, it endorsed the first report of the IGIE, which was published in Mexico in September; the same report that high level officials tried to discredit in the weeks that followed.

The IGIE report: strong questioning of the “historic truth” of the Ayotzinapa case

The IGIE report had 180 direct victims, among them six extrajudicial killings and 43 “forced disappearances.” It confirmed that “there was presence of different state agents (municipal, ministerial, and federal police) and we did not find that there were protective actions.” It noted mismanagement of evidence and questioned the “historic truth” presented by the then Attorney, Jesus Murillo Karam, who denied the involvement or the presence of the Federal Police and the army in the events. Another new detail that the report proposes is that there were five, not four, buses used by the students that day, a fact that – in the first instance – was denied by the authorities. Regarding video evidence, they presented a different bus. The IGIE suspects that it may have been a modified vehicle to transport drugs, taken unknowingly by the youths. This possibility opens new lines of investigation.

From the beginning, efforts to discredit the report were observed. Arguments were heard to the effect that the executive secretary of the IACHR, Emilio Alvarez Icaza (Mexican) has a conflict of interests; or pointing out that it should be the Mexican authorities that should be following the case. It is worth remembering that the same Mexican state asked for the help of the IACHR. One of the main actors who most questioned the presence of the IGIE has been the Mexican army, indicated by the report not for its action in the events but for its omission in what was happening. Unusually, the Minister for Defense, General Salvador Cienfuegos, offered interviews to the media. He opposed international experts interviewing soldiers of the 27th Infantry Batallion installed in the outskirts of Iguala: “We only respond to the Mexican authorities”, he declared. Critical media noted that, far from contributing to the image of the army, this posture increases suspiscions.

Doubts that are not at all international

In the middle of September, the Chamber of Deputies named eight people to set up an Ayotzinapa Special Committee, which began to interview various officials, including the ex-governor of Guerrero, the ex-attorney of Guerrero, and General Cienfuegos. The latter allowed members of the 27th Batallion only be interviewed in the presence of a superior to avoid “intimidation”. These interviews were formal and, in spite of what the Commission asked for, media have reported that the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has stopped the possibility that future meetings take the form of hearings.

As regards the actual population, polls show a high level of discontent. According to the Latinobarometer (Latinobarómetro) in 2015, Mexico is the country with least satisfaction with its democracy: 19% of those interviewed said that they were happy with their system of government, which represents half of the average for the region. Only 26% think that elections are carried out according to law. 21% think that the country is governed for the benefit of society and not for a few. Only 18% think that the nation is progressing.

An equally critical economic context

The same Latinobarometer shows that Mexico occupies the second last place in the evaluation of the internal situation economic situation. In a context of low economic growth, devaluation of the peso, deepening poverty and the fall in the price of petrol, various economic initiatives generated more concern than optimism.

In October, 11 countries of the Pacific Zone, including Mexico, finalized negotiations of the Trans- Pacific Treaty (TPT). its entrance into effect is still subject to the decision of legislators in each of the member countries. Among its supposed advantages are the reduction of tariffs and the possibility of competing in one of the world’s biggest markets. Nevertheless, the treaty has caused controversy as the negotiations that led to its elaboration were conducted in secret. From the little that has been leaked, a number of elements point to the increase of rigts of transnational corporations in unequal measure to those that correspond to populations. It would establish a system of resolution of conflicts between investors and states which would limit the power of the nation to control the potential abuses of foreign companies.

On another note, in December, the presidential project to create Special Economic Zones or SEZ (Zonas Económicas Especiales – ZEE), was backed by the Chamber of Deputies. It establishes that they can be developed and administered with extensions of up to 40 years. To set them up, the government can declare an area to be of public utility and expropriate lands. The first SEZs will be opened in Chiapas Port, the Inter-Ocean Corridor in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Oaxaca and Veracruz), and Lazaro Cardenas Port, (Michoacan). For the Indigenous and Campesino Front of Mexico (Frente Indígena y Campesino de México – FICAM), the said initiative “attempts to legalize pillage.”

GUERRERO: extreme expression of the prevailing crisis

The perception of political-social crisis and extreme violence endures in the state in spite of the change of government at state and municipal levels. Media have noted that, presumibly, some mayors and deputies of the LXI Legislature have connections with narcos, a key actor to understanding the levels of vioence that have been reached. Notably, after taking office in August, the new governor, Hector Astudillo (PRI), organized a public meeting in Acapulco with the secretaries for Defense, the Marine and Governance. It was announced that thousands of federal agents woud arrive to “reinforce security.” General Alejandro Saavedra Hernandez was also named as commander of the IX Region, general coordinator of the new public security strategy of Astudillo, which analysts consider to be in violation of the Constitution, pointing out that “in peace time, no military authority can exercise more functions than those which have a direct connection with military discipline.” The secretary of Government is Florencio Salazar Adame, ex-deputy, municipal president and PRI leader. In 2000, he worked on Vicente Fox’s (National Action Party; Partido Acción Nacional – PAN) campaign, with whom he would later be the coordinator of the “Puebla-Panama Plan and secretary for Agrarian Reform.

Shortly after, the Catholic bishops of the state stated that the new state government begins “in the middle of a profound social, political and economic crisis in terms of human rights.” In the document Committment to Guerrero and Peace (Compromiso por Guerrero y con la Paz), they demanded a program that unites the institutions and social sectors to rebuild the social fabric and the rule of law, as well as elaborating a plan for integrated and sustainable development, processes that they recommend should avoid dialogue with organized crime.

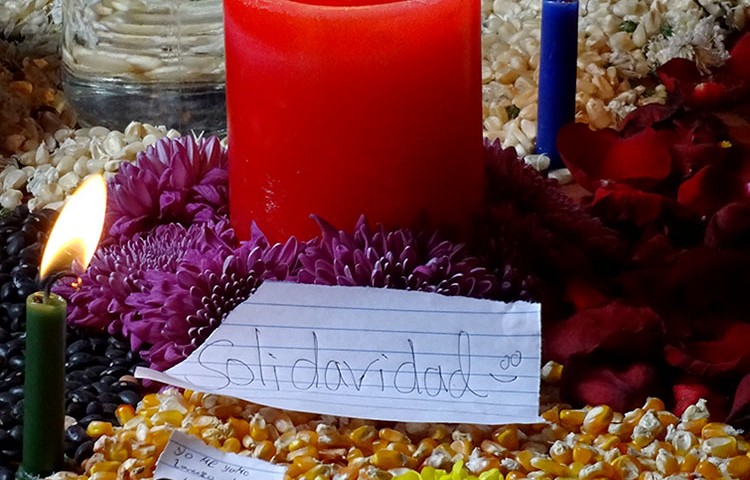

During the whole period, the relatives of the students of Ayotzinapa disappeared in 2014 carried out actions to clarify the events. In a meeting with President Enrique Peña Nieto in September, they presented eight demands to continue with the investigation. One of those is that the investigations continue through a specialized unit for the case, an option that in this instance was rejected by the President. In November, eight buses with some 150 student teachers from Ayotzinapa were intercepted by elements of the police in an operation to prevent them taking pipe full of petrol. The interception degenerated into a repressive act, leaving some twenty students injured, four of them seriously, and 13 detained. The attorney for the student teachers informed that the police burned three with cigarettes and stripped some to subject them to aggression. All were later freed. They demanded that Governor Astudillo Flores not criminalize social protest. In December, after a three-day sit-in near the presidential residence, mothers and fathers of the disappeared lifted their protest when the attorney Arely Gomez Gonzalez informed the families that their demand had been met: the creation of a new Specialized Investigation Unit (Unidad de Investigación Especializada), that will be overseen by the IGIE.

Another strong social movement: significant groups of teachers have opposed the educational reforms passed in 2013, particularly the diagnostic test that many see as a form of legitimizing selcetive firing. In Guerrero in December, the Ministry of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública – SEP) confirmed that a group of teachers registered for the evaluation with the aim of upsetting the process: some 70 of them cut off the network of 2,800 computers. Around 6,000 federal police were sent to protect the process.

Chiapas: blockades and more blockades

If we had to summarize the period covered by this analysis in just one word, in the case of Chiapas it would probably be “blockades”, given that there were road blockades put in place throughout the state by various actors as a form of incomformity, principally due to the results of the municipal elections in June. Some of those resulted in violence. All of them drastically limited free traffic for many days.

One relevant actor of these expressions of inconformity has been teachers. On October 18, the day marked for the diagnostic test, members of the 7th Section of Chiapas “were repressed violently when they were about to begin a congregation, which they described as peaceful, and which Section 40 [of the health sector] was going to join.” According to media sources, “the authorities reported that three policemen were beaten and one of them held by the teachers. The teachers denounced that three of their colleagues were injured by rubber bullets, four beaten by the police, and two arrested. Later, the police and teachers exchanged ‘hostages.'” In the attempt to re-convene in November, the CNTE held marches in which more than 30,000 teachers participated. After, the new dates for the evaluation were December 12 and 13, although at the last moment the authorities changed them to the 8 of the same month, attempting to stop the boycott of its application. Teachers tried to impede access to the installations, where educators were taken and held in military installations after congregating. There were confrontations with the police which left one teacher dead, six arrested, and numerous injured. David Gemayel Ruiz is the third educator to die in protests against the evaluation, following the death of two teachers in Guerrero in February and March. After negotiations with the federal authorities, the CNTE called for a return to work after a three-day strike.

Impunity intact

There are many examples of activities and reports made during the second semester of 2015 that point to the same reality: the ruling impunity. In September, in Masoja Shucja, municipality of Tila, some hundred people participated in a commemoration to remember the people murdered and disappeared in the zone between 1994 and 1999. In October, the displaced Tojolabales from the community of Primero de Agosto denounced that “due to the omission of the official authorities, the violation of our rights, death threats, kidnapping threats, threats of a new displacement, and harassment continue.” Also in October, the Civil Society of Las Abejas de Acteal (Sociedad Civil Las Abejas de Acteal) took part in a public audience with the ICHR in Washington about the Acteal Massacre (1997). Las Abejas reiterated that “this massacre was planned by the Mexican State.” Later, Las Abejas stated that “facing the cynicism of the Mexican State in denying their responsibility in the Acteal Massacre; we say (…) that we DO NOT accept arriving at a friendly solution.”

New claims

In September, Alejandro Diaz Santiz, a prisoner at San Crsitobal de Las Casas Penitentiary and member of the Voice of Amate, was moved along with 386 prisoners in 13 state prisons to another prison near Tapachula. In the operation, prisoners considered to be “high risk” were relocated, which the work group “No estamos todxs” defined as ‘political vengenace of the bad government against Alejandro, punished for supporting and raising awareness of the other prisoners.”

Likewise in September, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas – CDHFBC, also known as Frayba), reported that the Support Bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Bases de Apoyo del Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional – EZLN) in Tzakukum, municipality of Chalchihuitan, have been subject to death threats and physical attacks. Since July of 2015, there has been a conflict after members of PRI started to build classrooms in areas of common use without consulting the Bases. In December, CDHFBC also reported the arbitrary detention and lack of due process in the detention of Jose Alfonso Cruz Espinosa, also a Support Base of the EZLN.

On December 2, the Center of Women’s Rights of Chiapas (Centro de Derechos de la Mujer de Chiapas, A.C.) reported judicially and publicly threats and intimidation against them. As well as being watched, the claim refers to numerous calls which were even more worrying as the people who made them had private information about their staff.

Also in December, the home of Julio Cesar Ortega, collaborator of CIDECI – Unitierra Chiapas and part of the support team of the Sixth Commission of the EZLN, was broken into. On that day, four people violently entered his home. His 25-year-old son was there, who was beaten, tied, questioned about his father, and told that they has been paid to kill him. Having stolen some things of little value, the men left.

On December 16, after an assembly agreement, indigenous peoples of the Tila ejido reclaimed the common lands where the town hall was located and demolished the building. They pointed out that that they have gone to different levels of government for five devades without being addressed. Later they denied reports in local media saying that “there was no violence and even less confrontation.” They reported that the director of the municipal police shot at one of those who was involved in this phase of the recovery of land. They accused the mayor of reactiviating a paramilitary-style group Development, Peace, and Justice (Desarrollo, Paz y Justicia) which is said to be responsible for 86 executions, 37 forced disappesarances, and the forced displacement of more than 4,000 people between 1995 and 2000.

OAXACA: signs of criminalization of social movements

In November, the Governor of the State, Gabino Cue Monteagudo, sent his General Secretary of Government to give account of the V Report of Government at the local Congress. His absence was due to the announcement of a mobilization by Section 22 of the CNTE in the place where the Report would be made public, and due to this, was protected by almost 2,000 state and federal police. As in other states, the CNTE has opposed the diagnostic test with different forms of protest. A number of social and civil organizations coincide in that the repeated “strikes” against and criminalization of Section 22 have caused a state of citizen demobilization.

Previously, following the march in Oaxaca on October 2, during which the massacre of students in Tlatelolco in 1968 was commemorated, 52 people were detained. The Network of Women Activists and Defenders of Human Rights of Oaxaca (Red de Mujeres Activistas y Defensoras de Derechos Humanos de Oaxaca) denounced “the evident strategy with the aim of criminalizing the social movement.” Ten days later, all those detained had been released without charge.

In October, representatives of the Binni’zaa indigenous community of Juchitan, Zaragoza, reported that, after the block imposed on the construction and operation of the mega-project of Southern Wind Energy (Energía Eólica del Sur) on their territory, an order of suspension was given on all authorizations and permits given by the federal and local authorities. They denounced that “as a consequence of this judicial resolution, harassment of those who inposed the block has increased.” They ratified that in their case “there was no public consultation, as in January the project had been approved (…) but it wasn’t until June of this year that the supposed consultation was held, and it was only a simulation.”

In November, representatives of 50 organizations of the Southern Coast and Sierra (Costa y de la Sierra Sur) along with civil organizations denounced the existence of at least 14 hydroelectric projects on the coast of Oaxaca , as well as mining projects, which threaten the territory of the peoples of the region. During the Regional Forum “Rivers and Mountains in Danger” (Foro Regional “Ríos y Montañas en Peligro”), they said that many of these projects have been relauncehd by the federal and state authorities of Oaxaca.

Impunity remains intact in the case of the murders of Bety Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola (Finnish), committed in 2010 during a humanitarian caravan in the region of Triqui. On an official visit in October of MEPs, Satu Hassi and Ska Keller, no representative of the government of Gabino Cue Monteagudo received them. The Finnish MP, Satu Hassi, declared that that they decided to come to Mexico because “there are no advances, there is nothing, nothing has happened, and so, my conclusion is that there is a total lack of will” to detain the perpetrators of these crimes. Hassi added that “we see a very similar pattern between the case of Jyri Jaakkola and Bety Cariño and that of the 43 disappeared of Ayotzinapa.” She concluded that both cases are symptoms of the same disease, impunity.