2020

12/01/2021

FOCUS: Human rights in the hands of corporate goodwill

18/03/2021

O n December 10th, on the occasion of International Human Rights Day, the Report “Second Year, A New Human Rights Policy and Presentation of the National Human Rights Program” was presented by the Ministry of the Interior.

Regarding the situation of human rights defenders and journalists, it reported that in the period, 1,313 persons (426 journalists and 887 defenders) have been incorporated into the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and journalists. It also pointed out that said mechanism is currently the object of “profound transformations” seeking to move from a reactive to a preventive scheme. Alejandro Encinas, Undersecretary for Human Rights, Population and Migration, highlighted the fact that the Mexican government opened the space to the United Nations Committee against Forced Disappearances to hear individual petitions as one of the advances, “a demand from families for whom it was denied for years.” He announced the publication of the National Human Rights Program (PNDH in its Spanish acronym) that aims to “rethink the performance of the entire public administration in the field of Human Rights, assuming it as a cross-cutting axis of all public policy.” “There is a long way to go to exit the serious Human Rights crisis we are facing”, he concluded.

A diagnosis largely shared by Civil Society

In December, Espacio CSO for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists declared that it views some of the announcements and measures adopted by the State as positive. On the part of the executive branch, it highlighted the National Comprehensive Protection System that would promote “greater networking with the states.” It positively valued “the change in the legal nature of the Mechanism, making it possible to strengthen its structure”, as well as the incorporation of a differential and intercultural approach. The Legislative Branch recognized as progress the Law initiative regarding the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, better known as the Escazu Agreement.

However, Espacio CSO continues to view with concern the “lack of clarity in the timing for compliance with the route, as well as budgetary guarantees and labeled resources that ensure effective compliance with the measures.” It recommended greater dialogue with defenders, human rights organizations and journalists: “it is an essential factor to achieve the objectives set”, it stressed.

Subsequently, in February, the presentation of the report “Situation of the Defense of Human Rights and Free Expression in Mexico since the Pandemic” was carried out jointly by the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) with other organizations. It documents that in 2020, six journalists and 24 defenders, mainly environmentalists, were murdered.

Vulnerable groups even more so in the context of the pandemic

By mid-February, Mexico had totaled about two million cases of COVID-19 infection, and around 175 thousand deaths. In addition to the direct impacts of the health crisis, a worsening of several pre-existing trends has been observed, particularly for vulnerable sectors.

In November, within the framework of International Day for the Eradication of Violence against Women, mothers of victims of feminicides delivered a letter with more than 18 thousand signatures to President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), to demand justice and the cessation of femicides. In 2020 2,874 women and girls were murdered. Only 724 cases are being investigated as femicide.

In January, the Network for the Rights of the Child in Mexico (REDIM) presented a report entitled “The Year of the Syndemic and the Abandonment of Childhood in Mexico”, in which it highlighted that violence against this sector has multiplied during the pandemic. 63% of minors have experienced some type of violence, and during confinement, tensions at home increased by 34.2% compared to 2019.

Regarding migrants, in November, the “Report of the Findings of the Human Rights Observation Mission on the Southern Border of Mexico” identified that “the context regarding migration policy (…) became more complex and intensified, which was evident with the increase in militarization and border control, as well as the strengthening of the agreements between Mexico and the United States, coupled with this, was added (…) the health emergency.” In December, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH in its Spanish acronym), organizations and migrant shelters expressed their concern at the decisions that tend to militarize the National Migration Institute (INM in its Spanish acronym): “in 18 states, people with a military profile have been appointed to lead (…) that Institute.” They reiterated the need to direct efforts towards “a perspective of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law, rather than security, since this perspective contributes to the idea of the criminalization of groups of migrants, which further aggravates their situation of vulnerability.”

Adding to concerns about militarization…

In November, a US judge accepted the request of the United States Department of Justice to dismiss the money laundering and drug trafficking charges against the former Mexican Secretary of National Defense, General Salvador Cienfuegos, who had been arrested in October in California. The US authorities dropped the charges and delivered more than 700 documents on which the criminal accusation was based to the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico (FGR in its Spanish acronym). Cienfuegos was repatriated to Mexico and, in January, the FGR determined that there will be no criminal proceedings against him due to lack of evidence. AMLO assured that, although his government seeks to end impunity and corruption, it will not allow “retaliation, revenge, and inventing crimes.”

However, more than 300 organizations and groups of victims asked the president to remove the head of the FGR, Alejandro Gertz Manero, for failing to fulfill his duties in the case. They declared that their action “makes it clear that in Mexico the military are untouchable” and that the closure of the investigations “is also the absolute closure of the possibility of (…) investigating in an effective and efficient manner at the highest levels power.”

Another side of militarization: in December, AMLO announced the intention of creating an Armed Forces company to entrust the administration of three sections of the Maya Train as well as Chetumal, Palenque and Tulum airports. This is to seek a good administration of the projects, allocate pension resources to the Army and the Navy, in addition to guaranteeing security in the region.

Megaprojects and extractivism, “essential” activities…from the government’s perspective

In November, a letter signed by six UN Special Rapporteurs addressed to the Mexican government was published, expressing their concern about possible human rights violations related to the Maya Train, when the consultation process that should protect the right to free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples “would have been imposed to legitimize the project, since the decision had already been made.” They also stated that the information process was limited and culturally inappropriate. Lastly, they expressed concern about the situation of human rights defenders, in particular “about acts of harassment against those who require more information, more time for their decision or express their disagreement (…), as well as attacks on human rights defenders who have filed any legal action, through criminalization, marking and defamation, the denial of their indigenous identity and the disqualification of their work.”

Meanwhile, the project has continued to advance. In December, the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) authorized the Environmental Impact of Phase 1, which allows the National Fund for the Promotion of Tourism (FONATUR) to start with the works, although 16 conditions are imposed. Among them is to follow up on the agreements resulting from the 2019 indigenous consultation.

Several legal appeals have been filed. In December, a court ruled on the definitive suspension of the construction of new works on Section 2 in Campeche. This was in response to an injunction filed by more than 100 indigenous, rural, urban and coastal communities. The resolution prevents new works from being carried out on that section during the corresponding lawsuit.

Regarding extractive companies, in January, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN), denied the injunction presented in 2015 by the Macehual people of the Sierra Norte de Puebla, against the Mining Law despite calls from the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) and the National Institute for Indigenous Peoples (INPI). Indigenous peoples from various communities in the country and civil organizations considered that the ruling represents a setback in the construction of the multicultural State and the protection of the territories and biocultural heritage of the peoples. The Mexican Center for Environmental Law (CEMDA) questioned the decision to “validate a system that has historically stripped indigenous peoples of their territory, and that has repeatedly committed violations of their human rights.”

EZLN and CNI: in clear opposition

In January, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Indigenous Government Council (CIG) denounced that the pandemic has served the Federal Government for “the imposition of mega-projects and the militarization of the country”, in addition to which “it contributes to the war of extermination against our peoples, where health services and economic capacity are very scarce.” They declared that “Lopez Obrador’s lying words and his so-called fourth transformation are intended to create a wall that hides the war that is raging against the peoples and the life of Mother Earth, wanting to isolate us and present us as opponents of progress.” They announced, however, that “we will continue fighting until life triumphs over death, with our most powerful weapons: dignity, resistance and rebellion.”

In addition, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) reported that hundreds of organizations, artists, intellectuals and people from more than 30 countries, the CNI, the Indigenous Government Council (CIG) and the EZLN itself agreed to fight for humanity on the five continents. It announced that they will carry out “meetings, dialogues, exchanges of ideas, experiences, analyses and evaluations among those of us who are committed, from different conceptions and in different fields, to the struggle for life.” It ratified its “certainty that the fight for humanity is worldwide. Just as the ongoing destruction does not recognize borders, nationalities, flags, languages, cultures, races.” It reported that the activities in Europe will take place between July and October 2021, with the direct participation of a Mexican delegation made up of the CNI-CIG, the People’s Front in Defense of Water and Land of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala, and the EZLN. At later dates to be specified, meetings will be held in Asia, Africa, Oceania and America.

Chiapas: “Outrageous situation of structural violence”

In December, a Civil Observation Mission (COM) made up of 14 member organizations of the All Rights for All Network (Red TDT) as well as three international organizations visited Chiapas to document “the human rights crisis experienced by the communities.” The COM collected “testimonies with people affected by situations of forced displacement, land dispossession, arbitrary detentions, torture, harassment, threats, criminalization, among other attacks.” It considered “outrageous the situation of structural violence that is allowed and even promoted by the different levels of government and their little or no disposition to address the conflict, trivializing, discriminating and criminalizing the communities.” They urged the Mexican State to “cease the simulation and the lack of care for the communities and defenders.”

This approach is similar to what was expressed by Pueblo Creyente (Believing People) of the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas in a statement in January, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the passing of jTatik Samuel Ruiz (see Article): it lamented the systematic violence and inequalities , especially during the pandemic. It spoke of the lack of education, of employment, of the effects that children are suffering from not going to school and the lack of interaction with others. Faced with these and other permanent threats such as megaprojects or militarization, Pueblo Creyente said that the communities have sought to continue with autonomy, resistance and self-determination. However, there is an increasing danger in the defense of territory due to the increase in threats, surveillance and harassment. It also spoke of the increase in violence by armed groups and organized crime, and due to the proximity of the July elections. “As Pueblo Creyente we have to find a way to act that keeps us hopeful. Our option is for life”, it stressed.

“Definitive”(?) agreement in the Aldama-Chenalho conflict

In November, a humanitarian aid brigade that was delivering food to displaced families in Aldama was shot at by an armed civilian group allegedly from Santa Martha, Chenalho. In this attack, the nun Maria Isabel Hernandez Rea was injured. The mayor of Aldama stressed that at the time of the attack a Mixed Operations Base (MOB), made up of military and federal and state police, was 200 meters away.

The governments “have ignored the constant calls to stop the armed aggressions”, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba) stated. The diocese of San Cristobal urged the Mexican State to “disarm and dismantle the paramilitary armed civil groups in that area and, together with those who provide them with weapons, apply the weight of the law.”

In November, Frayba reported new attacks with firearms in Aldama, days after a “Definitive Agreement” was signed between this town and Chenalho, to resolve the long-standing agrarian dispute between the two municipalities. In addition to the properly agrarian component, Alejandro Encinas announced that the damage to the victims will be compensated and that cooperation will be sought between the National Guard and the state security forces to guarantee security. However, attacks have continued to date.

Numerous other hot spots

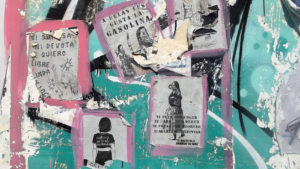

March held within the framework of the International Day against Violence against Women, Tonala, November 2020 © SIPAZ

In November, the Digna Ochoa A.C Human Rights Center located in Tonala denounced that one of its members, Nataniel Hernandez, and his family were victims of death threats and damages against their vehicle. The defender had gone to document a violent situation in Colonia Arenero due to a problem related to green areas that were invaded. In addition, the Center reported that for the same case it has requested precautionary measures from different authorities. However, “they have not been implemented and this has led to a wave of acts of confrontation, threats, discrediting, defamation, slander, and physical attacks”, it reported.

In November, the report “Violence against Women in the Context of a Pandemic” was presented, which reports on the “increase in family violence, sexual violence, cyber violence and, clearly, femicides.” This increase took the form of “18 femicides, two attempted murders, 34 intentional homicides, 12 attempted murders, and 54% occurred in the homes of the women themselves.” The difficulties of access to justice in confinement due to the “suspension of judicial and civil proceedings” are of particular concern.

In January, representatives of the Tzeltal people of the municipality of Chilon, together with Frayba and the Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez Human Rights Center (Centro Prodh), reported that they filed an injunction over the construction of a National Guard Headquarters in their territory, because they were not consulted. They also asked the Chiapas Attorney General’s Office to desist from prosecuting two ejidatarios who “were repressed and criminalized for demonstrating against said project.”

In January, Frayba reported having received information from the Patria Nueva Good Government Council denouncing that “members of the Ocosingo Coffee Growers Regional Organization (ORCAO) have attacked the Moises Gandhi community with firearms.” It recalled several other previous incidents of the same nature. Nor is it the only case of growing conflict around lands recovered by the EZLN, there are several others, one of them in Nuevo San Gregorio, municipality of Huixtan.

OAXACA: Vulnerability of environmental defenders opposed to megaprojects

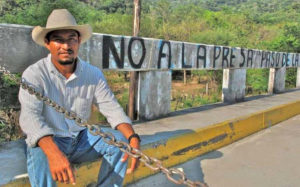

In January, Fidel Heras Cruz, community defender and president of Paso de la Reina Ejidal Commissariat, was murdered in the municipality of Santiago Jamiltepec. He was an active member of the United Peoples’ Council for the Defense of the Verde River (COPUDEVER), an organization that maintains active resistance against the Paso de la Reina and Rio Verde hydroelectric projects. The Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus (UCIZONI) also reported on “threats from powerful economic groups linked to the exploitation of stone material.” Ejido and municipal authorities, as well as civil organizations demanded that a thorough investigation be carried out so that the crime does not go unpunished.

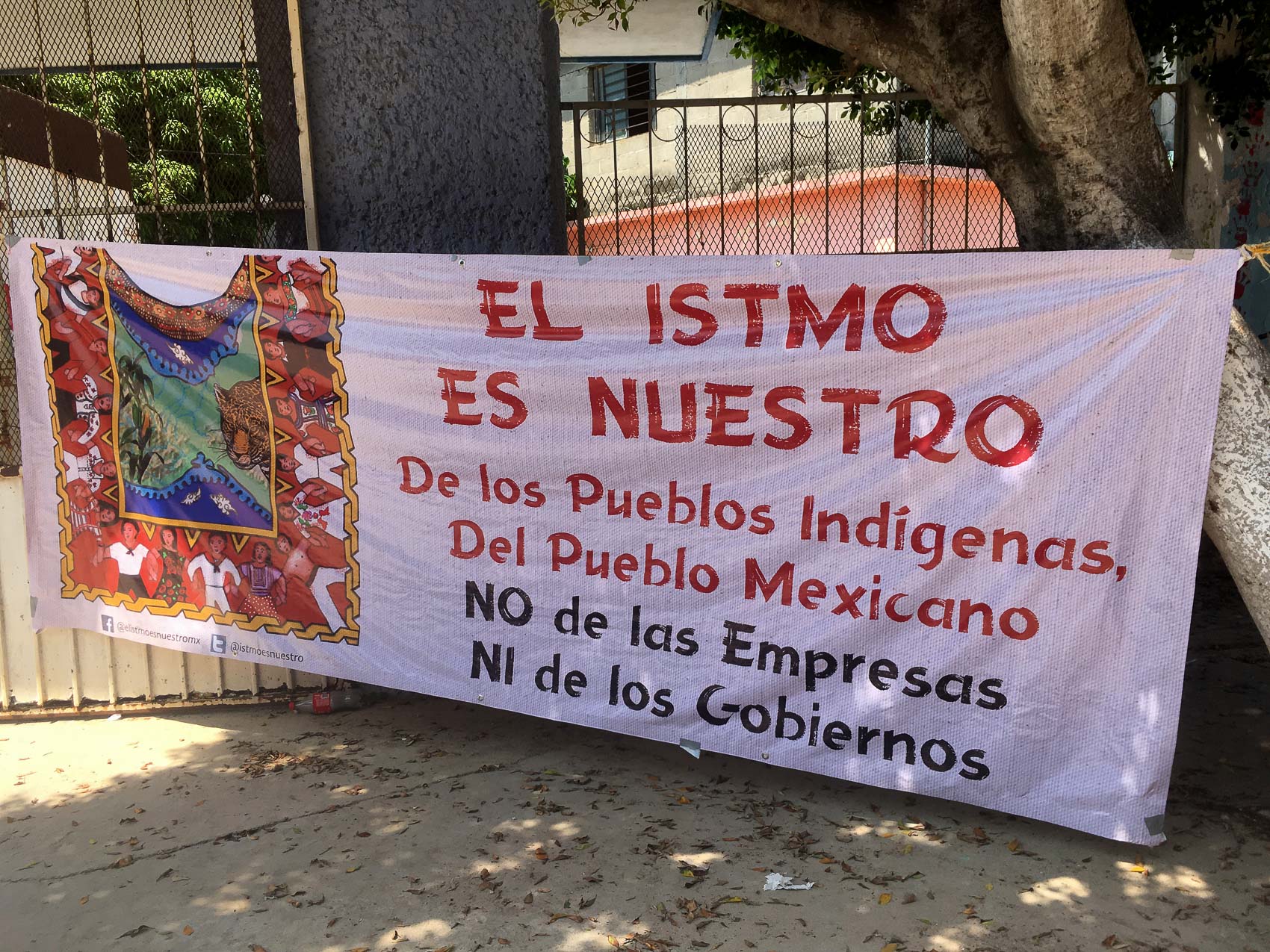

In November, UCIZONI and CEMDA denounced before the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner in Mexico (UNHCHR) the violations of their rights in the framework of the approval and implementation of the Trans-Isthmus Corridor. They asked him to urge the Mexican State to suspend the project until the peoples have “full information on environmental and social risks and impacts.” They detailed the irregularities in the consultation carried out in March 2019 which, they denounced, was not prior, free, informed, culturally adequate and in good faith as recommended by the international conventions ratified by Mexico. “There was no dialogue, but a government monologue”, they asserted.

Regarding extractive projects, in December, the No to Mining for a Future of All Front denounced that it has tried unsuccessfully to establish a dialogue with SEMARNAT. It denounced that the information presented by the Cuzcatlan Mining Company in the Environmental Impact Statement contains “false information.” Instead, it recalled that “the communities that inhabit the Central Valleys have witnessed water pollution, the emission of dust, noise, the driving away of wildlife in the region, the impact on the landscape, as well as serious violations of human rights and social conflicts produced by the project.” The Front urged refusal of the authorization of the Environmental Impact Report; guarantee effective protection of the environment against private interests; and grant the requested audience to “build solutions together with the affected peoples and communities.”

On another note, in November, the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity reported that 2,344 cases of violence against women have been documented so far during the government of Alejandro Murat. In addition, in four years, “1,005 women have been reported as missing (…) compared to 121 cases registered in the same period of government of Gabino Cue.” However, they assure that these figures do not reflect reality mainly because not all cases are reported. However, they consider that they reflect “a simulating, ignorant and denying government that maintains impunity in the face of pain and the demand for justice.”

GUERRERO: “Like a Night without Stars”

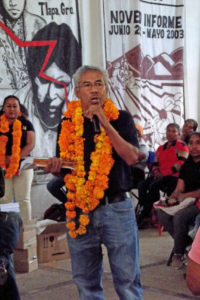

In December, La Montaña Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center presented a report entitled “Like a Night without Stars”, which identifies the main problems facing the state. Abel Herrera Hernandez, its director, said: “We have seen that this year, with the lockdown, the violence in Guerrero has increased. Above all, we have seen that the armed actors are acting with impunity. (…) We see an empowered crime that is entering the communities to subdue the population. And a subject authority because it is allied with other crime groups.”

He mentioned that the situation of journalists has worsened: “Three cases of journalists murdered in Acapulco, in Iguala, in Apaxtla have been documented (…) The power of crime is confronting defenders, journalists, social defenders, activists. And this is serious in a state like Guerrero, where impunity, (…) continues to prevail.”

Regarding the community police, he reported that “in the same territory as UPOEG, 15 members of UPOEG have been assassinated, including one of its main leaders. (…) They assassinated a coordinator of the CRAC. (…) We have documented eight cases of members of the Regional Coordination of Community Authorities who have been assassinated.”

Regarding the pandemic, he concluded: “The towns are abandoned, there is no one to hold onto (…) The women are the ones who are paying for the lockdown. We have documented seven cases of femicides that we are accompanying and 19 cases of violent deaths of women, six cases of missing women, five murdered girls.”

Regarding the accompaniment of the center of the Ayotzinapa case, Tlachinollan reported that, “in 2020, when the objective was to give a strong shift in the investigations, the issue of the Coronavirus arose, which has had a significant impact on the investigations and searches. However, these continued and as a result, by the month of April they began to have some responses. On September 26th of that year it was established that we have 80 arrest warrants issued. Of these those of Tomas Zeron de Lucio, head of the Criminal Investigation Agency, Carlos Gomez de Arrieta, head of the Ministerial Police, Captain Martinez Crespo, and Jose Angel Casarrubias Salgado, alias el Mochomo are notable.”