FOCUS: The tragedy of forced internal displacement in Mexico – one of the pending issues for the new government

22/09/2018Fund Appeal Letter

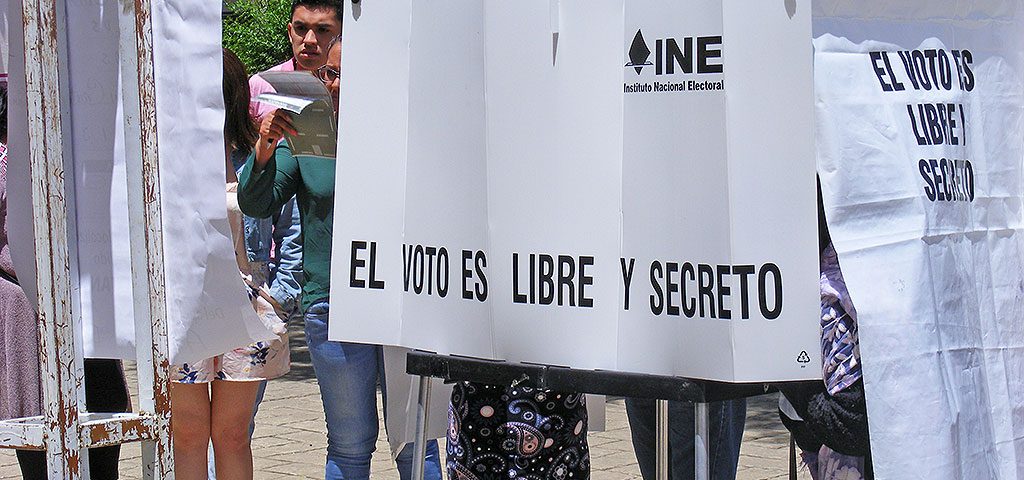

07/12/2018In Mexico, historic elections took place on July 1st which included a record number of political races: 18,311 public offices on the federal, state, and municipal level. Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), candidate for the coalition “Together we Will Make History” formed by the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), Labor Party (PT), and the Social Encounter Party (PES), was elected president of the Republic by a margin never seen before in Mexico: he won 53% of the vote.

His coalition also won a majority in both chambers of congress. The coalition also triumphed in five state governor races (Veracruz, Chiapas, Morelos, Tabasco, and Mexico City.) Pre-electoral violence reached limits never seen in Mexico. The Etellekt consultancy reported that 133 politicians were assassinated from September 8th, 2017 until the end of the campaigns and 548 assaults were recorded.

Although AMLO was leading in the polls for several months, such a clear victory was somewhat surprising, as such a weakening of the political parties who had ruled Mexico for more than 80 years- The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and the National Action Party (PAN), had not yet been seen.

Many analysts explain this trend by the decisions they made while power: the war against crime launched in 2007 (PAN) and the “structural reforms” of Enrique Peña Nieto’s most recent administration (PRI), which did not generate the development or welfare promised but instead led to a strong wave of protests against him.

The PRI and the PAN used all the means at their disposal to prevent the current scenario, although they accepted their defeat with a civility that many feared would not happen. In the pre-electoral stage, reports of vote buying, collection of voter credentials, dirty money, and overspending in the campaigns, and clientelist use of social programs were also reported. Undoubtedly, these strategies had helped to prevent AMLO becoming president in the two previous elections.

Many also attribute the scenario of these last elections to the fragmentation and internal disputes that occurred in the historical parties. The “Lopez Obrador effect” has also been highlighted, linked to his personal leadership and the perception of honesty associated with him in the midst of multiple cases of corruption that came to light. His proposed changes rallied support against a discredited political class. In addition, compared with his previous attempts, he tempered his discourse, appealing to the center, and made room for leadership that had developed in other parties, and before leaving discontented with them.

Despite the results, limited room for maneuver for the next government

Although he won more than 30 million votes, and although his party will have a majority in both houses, the margin of maneuver for AMLO when he takes power in December will be limited. He can make some adjustments to the budget but he will inherit a debt that exceeds 10 trillion pesos. Several analysts point out that power will continue to rest in the hands of the capitalist class and that it will seek to guarantee its interests and the balance of power in its favor.

The priorities of the new government suggest that it will seek to reduce corruption, privileges, as well as to fulfill promises of austerity; reduce violence with a security strategy different to that of the two previous governments; and modify the budget to facilitate a policy with the slogan “The Poor First.”

Regarding violence, one of the issues that has most afflicted the country, president-elect AMLO has already reported that “Listening Forums to Trace the Path of Pacification of the Country and National Reconciliation” will be held between August and October. They intend to identify proposals on themes such as the “national reconciliation pact, the reconstruction of the social fabric and peaceful coexistence, disarmament, demobilization, reintegration of members of organized crime and guarantees of non-repetition, consumption and possession of drugs, possession and carrying of weapons, and the reduction of sentences, as well as serious crimes. “

Since the beginning of the process, questions have been raised, both from movements of victims and civil organizations of human rights, regarding the format and possible scope of the process. However, the AMLO team has announced that, based on this, its reconciliation and pacification plan for the country will be ready in November.

Expectations from the social front and of human rights

“Comparte 2018” event in Morelia in the framework of the 15 years of the Zapatista Caracoles © SIPAZ

Outside the Listening Forums focused on the issue of violence, civil organizations and social movements have been posing several propositions to the incoming government with a series of concrete demands.

In June, ten presidential decrees were submitted that modify the status of existing protections of 40% of the water basins of Mexico, which represent 55% of the surface waters in the Nation. The executive branch raised this possibility as a measure of environmental protection. Other sectors question if it will allow the water to be leased for up to 50 years, among other options for extractive industries, since a large number of these basins are close to sites where megaprojects are planned. They agree that it is about opening the door to the privatization of water, ignoring the human right to water.

In August, the Mexican Alliance Against Fracking (AMCF in its Spanish acronym) urged AMLO and the legislators of “Together We Will Make History” to outlaw the method of extracting gas and oil, known as hydraulic fracturing, or more commonly referred to as fracking. It also called for a review of existing contracts (91 were given during Peña Nieto’s current six-year term), and to formulate a moratorium on new contracts as well as an energy transition plan.

“Comparte 2018” event in Morelia in the framework of the 15 years of the Zapatista Caracoles © SIPAZ

Also, in August civil organizations denounced the failure of the government of Enrique Peña Nieto to address the deficiencies of the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women (CONAVIM in its Spanish acronym). They stressed that violence against women in Mexico has cost the lives of 8,904 between 2014 and 2017 and that only 24% of cases were investigated as femicides. They also reported that, “the brutality and impunity that prevails in the cases recorded is alarming.” They also urged the incoming AMLO government to strengthen CONAVIM and “guarantee the right of women to a life free of violence.”

Nevertheless, other players do not expect any change with the coming to power of AMLO or with the parties that helped him win the presidency. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN in its Spanish acronym) stressed that, “the entire effort of the National Regeneration Movement Party, and Lopez Obrador and his team, since July 1st, has been to ingratiate themselves with the ruling class and with big capital. There is no indication (…) that says it is a progressive government, none. Their main projects will destroy the territories of the original peoples: the million hectares in the Lacandon, the Mayan Train, or the corridor of the Isthmus where they want to make [projects], among others.” The EZLN announced that they will continue in resistance in their communities and proposed the creation of a large civil organization at the national level as well as the creation of new non-indigenous and international civil councils. It was clear in any case that the announcement of the future cabinet of AMLO of proposing a constitutional reform that resumes the San Andres Accords on indigenous rights and culture, signed between the EZLN and the Mexican government, is not the format through which the Zapatistas plan to continue deepening their autonomous model.

Pending issues for the current and incoming governments on the international scene

Visit of the UN Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Chiapas, November 2017 © Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center

In June, representatives on freedom of expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the UN presented a report on their visit to Mexico in 2017. They noted that the country “is going through a deep security crisis that seriously affects the human rights of the population. One of the central aspects of the crisis is the weakening of the rule of law and local governance that has spread throughout the country.” “In addition to the use of violence in all its forms, criminal players and public authorities try to co-opt journalists for their own purposes and coerce them to disseminate information that favors criminal organizations or harms their opponents.”

In July, the organization Global Witness published a report titled “At what price? Irresponsible companies and the murder of people defending the land and the environment in 2017.” In the case of Mexico, it stressed that, “the collusion between companies and authorities and the presence of organized crime are factors that in Mexico affect the murder of environmental defenders, which multiplied from three cases to 15 between 2016 and 2017, 13 of them indigenous.” It called on the next government to address the problem “on a priority basis”, and to ensure the participation of communities and civil organizations in the decision-making process regarding mega projects.

In August, in the context of International Day of Indigenous Peoples, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indienous People for the UN, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, published a report on her visit to Mexico in 2017. She pointed out “the considerable gap between the legal, political and institutional reality, and the international commitments assumed by the country.” This, in “a context of profound inequality, poverty, and discrimination against indigenous peoples that limits their access to justice, education, health, and other basic services.” “To the lack of self-determination and prior, free, informed, and culturally appropriate consultation, are added territorial conflicts, forced displacements, criminalization, and violence against indigenous peoples,” she stressed.

CHIAPAS: Elections at all levels

In Chiapas, the July elections took place on federal, state, and municipal levels. At the federal level, MORENA received more than a million votes. Rutilio Escandon Cadenas was elected as governor with more than 39% of the vote. The coalition Together We Will Make History also won the majority of the local councils and the most important cities of the state.

However, this victory took place in such a way which insured that popular election were not in the hands of its historical militants, but rather in those of figures associated with the current governor of the Ecological Green Party of Mexico (PVEM in its Spanish acronym), Manuel Velasco Cuello (MVC). The most controversial case was that of Eduardo Ramirez Aguilar, who will be a senator for MORENA for Chiapas. As a member of the PVEM during the administration of Manuel Velasco, he was secretary of government and a local deputy. This is not the only case, and for this reason some consider that there was a secret alliance between MVC and MORENA in the state prior to the elections.

During the campaigns, the bishops of Chiapas denounced that “the system of political parties has been the cause of divisions and conflicts in communities and peoples due to the corruption of local authorities, the purchase of votes, coercion with social programs, misleading propaganda, false promises, the distribution of food and other objects to condition the voter, etc.” They pointed out that “the intervention of organized crime in the selection or imposition of candidates and the existence of illegal armed groups at the service of political, economic, or criminal interests is verified.”

The Electoral Prosecutor’s Office reported that it has initiated 38 investigations into violent incidents that occurred during the election day (including several murders). The Chiapas Electoral and Citizen Participation Institute (IEPC in its Spanish acronym) later reported that municipal elections were contested in 67 of the 122 municipalities of Chiapas, as well as in ten of the 24 districts for local deputies.

Human Rights: cases that will be passed on to elected candidates

Manifestation against growing violence against women in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, May 2018 © SIPAZ 2018

In June, the petitioning organizations of the Declaration of Alert of Gender Violence against Women (AGVM) denounced “the lack of commitment of the state government to evaluate the implementation of the measures ordered in the AGVM.” They stated that from their permanent monitoring and with the reports of the authorities, they find “serious omissions and faults of truth in the evidence that is presented as compliance of the AVGM.”

In August, members of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI in its Spanish acronym) of the Northern Zone of Chiapas reported being victims of threats and assaults in different incidents that occurred in the municipalities of Tila, Salto de Agua, and Yajalon. They reported that, “we are being threatened, harassed, intimidated, blamed for crimes, and being dispossessed of our lands.” They warned that “they can no longer leave their homes or go out in their communities because they have been victims of kidnappings, assaults, and theft of goods in the vehicles that take them back. There is no justice even though there are complaints before the Public Ministry, (…), high powered weapons are fired, even with the presence of the Mexican Army (SEDENA in its Spanish acronym). There is no authority to stop the wave of insecurity and violence. We demand justice, peace, and tranquility.”

Also, in August the Human Rights Area of the Diocese of San Cristobal reported that 57 parishes collected 40,400 signatures in support of an injunction filed by the National Association of Democratic Lawyers (ANAD in its Spanish acronym) against the water reservation decrees taking into account the “lack of prior consultation”.

OAXACA: Violence beyond the electoral context

The violence that was witnessed during the electoral campaigns is added to the prevalence of violence in Oaxaca, with tolls that continue to rise and that come from different types of conflicts.

In July, there was an armed attack between residents of San Lucas Ixcotepec and Santa Maria Ecatepec, the result of a conflict over land boundaries. The death toll was 13. Civil organizations reported that more violent events have occurred due to other agrarian conflicts in the Sierra Sur, which is concerning due to the absence of the State in the settlement of agrarian conflicts and because their only response is the militarization of the region backed by the Law of Internal Security.

Also, in July the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory (APIITDTT in its Spanish acronym) and the Community Assembly of Alvaro Obregon denounced the murder of community police member Rolando Crispin Lopez. They recalled that “since 2012, the community of Alvaro Obregon has been fighting to defend its territory against the Wind Power Company of the South, formerly known as Mareña Renovables, and in February 2013, community police were established.”

In July, the Committee for the Defense of Indigenous Peoples (CODEDI in its Spanish acronym) denounced the installation of a checkpoint by the military near the site of its training center in Santa Maria Huatulco. This happened just five months after the murder of three CODEDI members at the hands of an armed commando when they were returning from a meeting with the state government, just days after the murder of its Regional Coordinator in the Sierra Sur. CODEDI has also reported surveillance, threats and house searches. All this “without any progress so far in the judicial investigation.” For CODEDI, the underlying cause of this violence is the construction project of three hydroelectric dams on the Copalita River. The Civil Area of Oaxaca denounced “the military occupation of territories where people struggle against the exploitation of natural resources”, “the excessive increase of aggressions against all defenders and members of the Oaxacan social movement”; as well as “the lack of interest and lack of response from the Government of the State regarding this situation.”

In August, before the election results, the Coordination for the Freedom of Criminalized Defenders in Oaxaca demanded justice for 33 human rights defenders who are under judicial process. It requested a meeting with AMLO, to “address one of the central issues raised by the agenda of social movement in our country.”

GUERRERO, “the least safe and bloodiest state in the country”

In Guerrero as in Oaxaca, the electoral factor was just one of the components which contributed to the violence that has been sweeping the state in recent decades. Regarding the paradigmatic case of Ayotzinapa, in June, a federal court ordered the PGR to reinstate the investigation of the forced disappearance of 43 students from the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa in Iguala, in September of 2014. It ruled that the investigation “was not prompt, effective, independent, or impartial.” The court held that there is “sufficient evidence to presume that the confessions and accusations against co-defendants were obtained under torture” and “in addition to the fact that in Mexico there is no independent prosecutor’s office, it was determined to create a commission of inquiry for truth and justice.” The ProDH Center, representative of the families of the missing students, considered that “it comes to confirm that the truth in the Ayotzinapa case is not stated. By virtue of the judgment, this assessment no longer comes only from international pressure, but has been established by a national court.” It demanded “a public commitment to fulfil the ruling by the end of the six-year term.”

In response, in July, “given the unusual legal offensive – composed of more than one hundred legal appeals – unleashed by the government of Enrique Peña Nieto against the ruling (…), and in anticipation that the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation must resolve several of these appeals”, relatives of the missing students asked the Supreme Court not to “bend to the pressure of the President and to be on the side of the truth and the victims.” The ProDH Center noted: “This government, far from using its forces to locate the students, has used them to attack the judgment of the Court.”

Another case that has been emblematic in Guerrero is that of the Regional Coordination of Community Authorities – Community Police (CRAC-PC in its Spanish acronym). In July, Governor Hector Astudillo Flores promoted a reform to Article 14 that addresses the rights of indigenous peoples in Guerrero and removes the words “community and rural police” from the constitutional article. The reform establishes that the resolutions issued by the community justice systems will have to be in accordance with the current legal order and be validated by state judges. The CRAC-PC denounced this reform, saying that it promotes the subordination of the community system to the state government. Tlachinollan said that the reform “is a blow to the struggle of the indigenous peoples of Guerrero in that they are denied the status that is internationally recognized.” It stressed that the people “are not going to ask for permission as they have never asked for 24 years to say enough is enough to a system of absolute, corrupt justice and security, in collusion with organized crime.”

In Guerrero, there are at least 18 armed groups of self-appointed community police officers with a presence in at least 38 of the 81 municipalities in the state, of which only the CRAC-PC is covered by Law 701. Given the reactions of rejection, Astudillo Flores declared that there is a “bad interpretation” regarding the contents of the reform, emphasizing that the purpose is to insure there are no armed groups “on each road”, and that “that has to be regulated.”

On a more hopeful note, in June, a 19-year conviction was issued against two soldiers accused of the crimes of rape and torture, stemming from the events that took place in Guerrero in 2002 against the indigenous woman Valentina Rosendo Cantu. This ruling is a response to an order by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2010.“This is the first time that Mexico complies with its obligation to investigate, prosecute, and punish the military personnel responsible for human rights violations. Following a ruling by the Inter-American Court (…) it is a milestone and a proof that impunity can be broken despite there being no will”, said the Center for Justice and International Law for Central America and Mexico (CEJIL in its Spanish acronym). For the organizations that have accompanied Valentina, “this emblematic case demonstrates the serious consequences generated by the participation of the Armed Forces in the work of civil security and should be a further call for the State to change its public security policy.”