In December, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) offered a message celebrating his first year of government. He stressed that of the 100 commitments he made during his campaign, he has already fulfilled 89.

He listed a series of achievements such as the reduction of fuel theft, the creation of 648 thousand new jobs, a 16% increase of the minimum wage, an annual inflation of 3%, the stability of the peso against the dollar, the coverage of government programs (at least one welfare program reaches half of Mexican households and 95% of indigenous peoples, he said). On the issue of security, he noted that “between 2006 and 2018 the government sought to solve insecurity and criminal violence through actions of military and police force, without addressing the substance of the problem,” a strategy that left a “dreadful balance” of deaths , disappeared and a human rights crisis.

National and international media questioned, however, the administration of AMLO over zero economic growth in its first year, as well as its inability to reduce violence, as there were more than 28 thousand violent deaths between January and October. The government itself also recognizes that in the first year of government, 9,164 missing persons were reported, of which only 43% were located; so there would be 61,637 missing in the country (still missing data from 11 state prosecutors).

Human rights crisis: “When Words Are Not Enough”

In November, Amnesty International (AI) presented the report “When Words Are Not Enough” in which it takes stock of human rights after the change of government. “The government of President Lopez Obrador has shown a willingness to move forward partially in some initiatives, especially on the issue of disappearances in the country. However, (…) there are no substantial changes in the lives of millions of people facing a very serious human rights crisis that has lasted for more than a decade. The very high levels of violence that undermine the right to life, the torture that is still widespread, the alarming rates of violence against women, and a more lively militarized security strategy than ever, are a sign of the tragic reality”, Erika Guevara Rosas, director of Amnesty International for the Americas, said. AI said it sees “an abysmal incongruity between what the government says and what it then does. It promises a more humane treatment for migrants in need of international protection, but sends the National Guard to persecute and detain them. He says he will protect human rights defenders and journalists, but publicly discredits them.” AI concluded that “the government has to stop blaming previous administrations for the situation and, instead, accept responsibility for what is happening in the present and seek solutions to address the serious outstanding issues.”

In a similar assessment in January, the National Network of Civil Human Rights Organizations “All Rights for All” (Red TdT) stated that “good intentions do not guarantee the consolidation of an adequate model of justice procurement ( …) The questioning of the importance of autonomy and independence for a more efficient and expeditious justice seems worrying to us.”

Another controversial issue took place in November, when the Office in Mexico of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) emphasized the importance of guaranteeing the independence and autonomy of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) after Rosario Piedra Ibarra was elected as the new president of the organization, despite opposition political parties as well as human rights groups and victims calling for her not to take office. There was evidence of incongruities and alleged fraud in the election process. In December, a judge agreed to process the injunction brought by the independent senator Emilio Alvarez Icaza against the irregularities that were recorded in the process. One of the requirements to fill the position is “not to perform, or have held the position of national or state leadership in any political party in the year prior to appointment.” It has been confirmed that Piedra Ibarra was a national adviser of the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA, the party in power) until last November. Although it is the first injunction that has been successful, it is far from being the first complaint linked to this appointment.

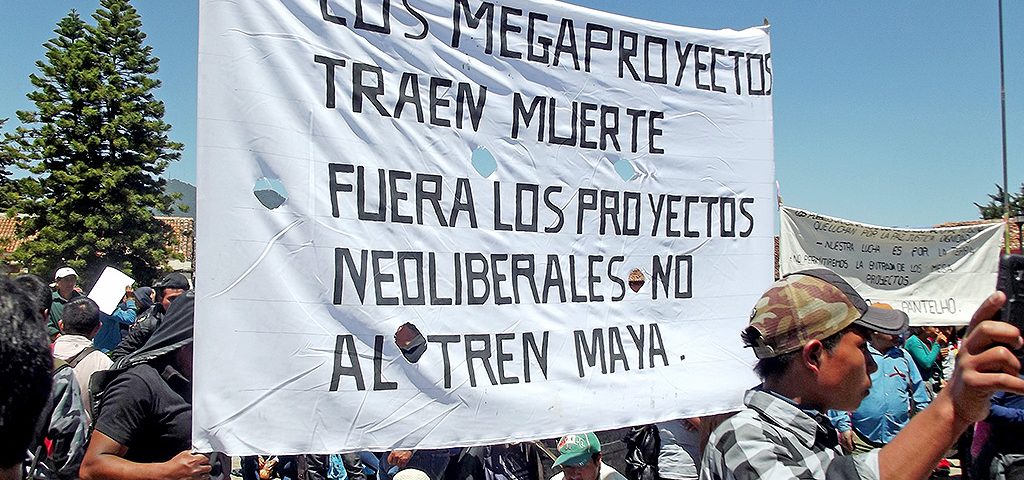

In February, Frontline Defenders (FLD) reported that Mexico is the fourth most dangerous country for human rights defenders. It is also the most dangerous country for environmental defenders and those who oppose megaprojects. The TdT Network sees a connection between violence against defenders and government policies: “There is a clear clinging [by the President] to the construction of his projects. The Mayan Train (…), the Dos Bocas Refinery, Tabasco, and the Santa Lucia airport are the flagship projects of this sexennium and the three are being imposed on communities, all three face injunctions, and large opposition movements. Currently, an extractivist policy continues, where economic development is based on the dispossession of peoples.”

Megaprojects and rights of indigenous peoples: clashes of different visions

In December the Indigenous Consultation regarding the Mayan Train ended. According to the authorities, 93,000 participants voted in favor, while 7,500 participants voted against. The UNHCHR said that this process “has not met all international standards.” Regarding the limitations of the informed nature of the process, it noted that “the call, the protocol, and the information presented only referred to the possible benefits of the project and not to the negative impacts that it could cause.”

The UNHCHR also observed that “as a consequence of the way in which the project was presented (…), the people of the communities expressed their agreement with the project as a means to receive attention to basic needs (…), a logic that affects the free nature of the query.” It also expressed concern about the cultural adequacy of the process, when “the definition of who to consult, where to do it, and at what time it was established unilaterally by the authorities.” It deplored the low participation and representation of women and that “the majority of those who participated were municipal and ejido authorities, leaving out other groups and people who are part of the communities.” It also stressed that the informative and advisory assemblies sought to “establish agreements with the communities regarding their participation in the implementation and distribution of benefits, which could imply that the project will be done independently of the outcome of the consultation.”

Indigenous communities belonging to the Peninsular and Ch´ol Maya people, settled in Xpujil, Calakmul, Campeche, members of the Indigenous and Popular Regional Council of Xpujil (CRIPX), reported that in January, the Judicial Branch of the Federation granted them a provisional suspension of project execution. Fonatur reported that none of the corresponding institutions were officially notified about the suspension.

It is not surprising that the possibility of presenting a reform to the Federal Injunction Law “to prevent (…) stopping public works” has been debated. According to Proceso, some legislators consider that “the current federal government has promoted important projects from its inception, which have been halted by suspensions granted through injunctions, causing damage to economic and social progress.”

CHIAPAS: Governor reports progress, NGOs report setbacks

In December, Governor Rutilio Escandon Cadenas (MORENA) presented his first government report emphasizing that “in Chiapas there is governance and the rule of law prevails” and that “we are a government that privileges permanent dialogue with all social sectors and there is justice for everyone.” He stated that “the ostentation of the rulers is over.” He said that one of the achievements is that “more than 32 thousand hectares have been rescued recently, between privately owned buildings and protected natural reserves.” He also affirmed that the level of crime went down and that impunity has ended.

Several media outlets, however, published critical assessments regarding the performance of the Escandon Cadenas government. Regarding crime, the Chiapas Citizen Observatory (OCCH) documented that Tuxtla Gutierrez, San Cristobal de las Casas, and Tapachula recorded high-impact crimes with rates above the national average in 2019. These media organizations highlighted that within this period, six of the 24 murders of human rights defenders in Mexico happened in Chiapas. They also stressed that the state is one of the ten main authorities indicated in the CNDH Recommendations Follow-up Report. In November, several civil organizations indicated that since the beginning of the year there had been 166 violent deaths of women, of which only 76 were classified as femicides.

Opposition to megaprojects: parallels with the national context

Respect for Life, Land and Territory of Peoples, Pilgrimage of the Believing People, January 2020 © SIPAZ

In December, members of several parishes and the department of human rights of the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas delivered a letter with seven thousand signatures to UN agencies expressing their disagreement because they have not been consulted for the construction of megaprojects such as the Mayan train and the San Cristobal-Palenque highway. They denounced that “it has ignored our disagreement and the destruction of our territories continues. Simulating a consultation, the State intends to strip us of our culture, traditions, and customs, dividing us to achieve the extermination of the original peoples.”

In February, in a pastoral letter the bishop of the diocese of San Cristobal de las Casas, Rodrigo Aguilar Martinez, stated that in Chiapas there are megaprojects “with which the people are affected.” He asked “how can they not mean enormous benefit to some and dispossession of others? How to integrate development – always with human and ecological criteria – into the most disadvantaged populations?” Aguilar Martinez also said that “the dispossession is also present through the loss of cultural roots caused by racism and discrimination, and government policies that do not take into account the word of the original peoples.” He said that the national security project “may be very well thought out and planned, but intermediate, and especially final instances often result in the dispossession of territories, which is achieved through various strategies such as forced displacement, threat, deception in the purchase of land, pressure with social programs, coercion through laws that favor the powerful, and violence that occurs through federal, state, and municipal police, the Army, the Navy, and the Guard National, as if through armed groups, paramilitary, or drug trafficking groups.”

Other human rights concerns

In December, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights (Frayba) announced that it presented an injunction for the “freedom of the survivor of torture, victim of violations of due process, and currently in arbitrary deprivation of liberty, Juan de la Cruz.” Frayba filed the injunction, noting that since 2016 there was a recommendation for freedom for Juan de la Cruz with a suspended sentence issued by the Reconciliation Board. In addition, they denounced harassment against its staff and those who make up the Collective of Relatives of Prisoners in Struggle “who we received in November and so far in December have recived threats of death, surveillance, harassment, and intimidation, in the context of the struggle for the freedom of indigenous prisoners, in particular of Juan de la Cruz Ruiz.” In light of these facts, Frayba declared that “an adequate protection response has not been obtained from the mechanisms of the Mexican State (…) minimizing the situation of risk that due to the circumstances, we believe is coming from agents of the State itself.” De la Cruz was released a few weeks later.

In December, human rights centers documented a new forced displacement of a community in the municipality of Chilon. They pointed out that 65 people were displaced from San Antonio Patbaxil and that “the same aggressor group displaced the population of the Carmen San Jose community” in 2018. They denounced that those displaced from the two communities “are in neighboring communities, in the municipal center, and scattered in the mountains, mostly without food or shelter, surrounded by armed civil group that are preventing their safe return.” They stressed that three more communities are at risk of being displaced.

Combo for Life: December of Resistance and Rebellion

The month of December was marked by multiple activities convened by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and parts of the “Combo for Life: December of Resistance and Rebellion”. This event included the Second Edition of the Puy Ta Cuxlejaltic Film Festival; the first Dance Event “Báilate otro mundo”; the Forum in Defense of Territory and Mother Earth in coordination with the National Indigenous Congress (CNI); the Second International Meeting of Women who Struggle; and, the celebration of the 26th anniversary of the beginning of the “War against Oblivion.”

In the midst of these activities, the Fourth National Assembly of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the Indigenous Council of Government (CIG) stated that “the bad government is committed to the dismantling of community fabrics, by promoting internal conflicts that stain communities with violence, among those who defend life and those who decided to put a price on it, even at the cost of selling future generations for the millionaire benefit of a corrupt few, who are served by the armed groups of organized crime.” They affirmed that “our peoples, nations, and tribes will continue to care for and defend the seeds of resistance and rebellion in the midst of death.”

During the event to commemorate their armed uprising, the EZLN stressed that: “They say there are no more Zapatistas. That we are very few in resistance and rebellion. (…) And every year the bosses congratulate each other saying that they have finished the indigenous rebellions. (…) But every year (…) we show and shout: here we are!”

OAXACA: Land and territory in the center of many struggles

In January, before the implementation of the Trans-Isthmus Corridor in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus (UCIZONI) submitted a complaint to the CNDH denouncing that “the ‘consultation’ exercises (…) were carried out without complying with the minimum established standards.” It requested that a new consultation be carried out in accordance with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO). For its part, the various municipalities of the Isthmus requested from the Secretary of the Environment Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) the holding of a public consultation that confirms the environmental impact of the expansion of the railroad between Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, and Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, one of the central works in the Corridor proposal. In February, Victor Manuel Toledo, head of SEMARNAT, acknowledged that the consultations “were not technically adequate” but “legitimate”, and that “the projects will go ahead” (see Focus).

In other processes in which megaprojects are being sought to be stopped, in February, the Non-Mining Front for a Future of All reported that SEMARNAT denied the authorization of the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) to the San Jose II Project, from the mining company Cuzcatlan, a subsidiary of Canada’s Fortuna Silver Mines. It considered that it is a partial victory since SEMARNAT recommended that the company to present a new EIR. It confirmed that “Fortuna Silver Mines does not have the authorization of the community assemblies in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, (…) we will not grant any municipal or agricultural permit to any mining company.” Also in February, authorities of the Zapotec municipality of Capulalpam de Mendez announced that they had won an injunction against the Canadian mining company Continuum Resources LTD and the Mexican mining company Natividad y Anexas, due to a lack of consultation.

Meanwhile, attacks on human rights defenders remain constant. In December, members of the Committee for the Defense of Indigenous Rights (CODEDI) announced protest activities to demand the release of Fredy Garcia, who was arrested last November. The International Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders believes that his detention is framed “in a pattern of systematic attacks against CODEDI in the last 21 months, including five murders, two assassination attempts, six arbitrary detentions, three incidents of raid and robbery, as well as permanent threats and the militarization of the area where the CODEDI training center is located.”

Finally, according to the statistics of the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP), from January to November 2019, 132 murders of women were committed in the state while “only 27 deaths are investigated as femicides”. Gender violence has reached municipalities that had not been considered in the Declaration of Alert for Gender Violence, in which only 42 municipalities of the state’s 500 are included. The National Citizen Observatory of Feminicide (OCNF) claimed that “more than a year after the declaration, the results are almost null and contrary to this, to the problem of feminicide, the increase in the disappearances of women, girls, and adolescents is added.” In addition, 1,562 sex crimes were reported, and only 502 are being investigateed.

GUERRERO: a tragic picture

In January, parents of the 43 students of the Ayotzinapa Normal School who disappeared in 2014 and the Federal Government agreed to reinstate the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (IGIE) in the investigation of the case. The subsecretary of Human Rights, Alejandro Encinas, acknowledged that a year after the Commission for Truth and Justice was created in the case, one of the most emblematic in the country, there are no “tangible results”. A month earlier, at the headquarters of the Ayotzinapa School, relatives of students who lost their lives in other events since 2011 announced the formation of the Committee The Forgotten Others that will seek justice in their cases.

In the few advances, in December the chief of staff of the MORENA city council of Tlapa de Comonfort, Marco Antonio Garcia Morales, was arrested for his alleged participation in the October disappearance and murder of activist Arnulfo Ceron Soriano, leader of the Popular Front of La Montaña (FPM). He is one of the people that Ceron Soriano himself had pointed out for corruption and for having links with organized crime and for whom he had held responsible for what could happen to him.

In recent months, clashes between criminal groups caused further forced displacements in the mountain region of the state. According to the “José María Morelos y Pavón” Human Rights Center, some 6,500 people have been forcibly displaced due to violence in the state. Milenio newspaper reported that there are nine thousand more people at risk of displacement in the same area due to disputes between criminal gangs.

At the end of December, an incident that reflects the desperation of the displaced population occurred when “a convoy with members of the National Guard, the Mexican Army, and the Special Forces Unit of the state police, went up to the community El Naranjo”, generating “expectations among displaced families” who are located in Chichihualco and who believed that their arrival would allow a return to their homes. Upon retreating, federal troops met “about 100 displaced (…) who blocked the road.” Tlachinollan Human Rights Center reported that these officers “not only assaulted some elderly people but also human rights defenders and journalists. The director of the Morelos Center, Manuel Olivares, for championing the claims of the displaced persons, was detained and deprived of his cell phone, computer, and documents related to the case. His vehicle was damaged. The defender Teodomira Rosales was subjected to blows and had a gun pointed at her by a policewoman. They jumped on journalists to prevent them from registering their misdeeds.”

Also in January, the murder of ten musicians in Chilapa and the presentation by the Regional Coordinator of Citizen Authorities-Founding Peoples (CRAC-PF) of children as new members of the community police again highlighted the situation of insecurity. The incorporation of these children (mostly orphaned by violence) in which they were making tactical movements for combat, generated multiple reactions. The Network for the Rights of the Child in Mexico (REDIM) considered this integration a “desperate act” to get the attention of the State. It urged the authorities to “attend to the so-called citizens and human rights organizations to build a national strategy to stop armed violence against children and adolescents.”