2016

29/04/2017

FOCUS: Controversial interior Security Act proposal on the tenth anniversary of the war on drugs

27/06/2017In the first months after Donald Trump took office as President of the United States, counterweights have been noted in the American political system that prevent him in the short term from making all his campaign promises public policy. Many of them would have an impact on Mexico first.

Protest in front of the Ministry of the Interior a day after the murder of Javier Váldez © Noé Pineda Arredondo

Regarding migration, the United States has announced new rules that will make detention and deportation of undocumented persons easier. They promote the immediate deportation of persons who have been convicted or charged with a crime, without specifying the type or severity. François Crepeau, UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants, noted that “their management of irregular migration closely resembles anti-alcohol policies during the prohibition or war on drugs. Criminality and the black market appear and many rights are violated with programs of zero tolerance.”

It is not only Mexican migrants who will be affected, but migrants of any nationality who enter by the Southern border. By the same token, from being a transit country, Mexico is becoming a destination country, while the return of compatriots is speeding up population growth and strong pressure for the country.

On the economic level, Trump’s approach of renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) could prove disastrous because of the high level of integration between the US and Mexico. According to Proceso magazine, Mexico is the second largest consumer of US goods and is the third largest supplier in the United States. Therefore, “canceling the FTA, as threatened by the northern demagogue, would increase prices and inflation in the United States, as well as raising industry costs in the region, putting jobs at risk and decreasing competitiveness.”

In terms of security, Mexico finds itself within the national security perim of the United States. In February, Donald Trump signed an executive order for what he called “breaking the back” of drug cartels and spoke of US intervention beyond its borders. In April, a conference on Security in Central America was held in Quintana Roo, Mexico, where installing a base of the US Southern Command on the border of Guatemala was discussed.

Enrique Peña Nieto’s government has sought to maintain a “respectful and constructive” relationship with the new US administration, with a style that some analysts consider too conciliatory.

Violence and Human Rights in Mexico: some progress but a long way to go

Last February, Amnesty International (AI) presented its annual report. The Mexico 2016 section tells of widespread violence and military personnel in public security operations, torture, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detention, a refugee crisis, threats and defamation of human rights defenders and journalists, among other things. In presenting the report in Mexico, the Executive Director of the Mexican section of AI was synthetic: “We are in one of the worst human rights and justice crises.”

Protest in front of the Ministry of the Interior a day after the murder of Javier Váldez © Noé Pineda Arredondo

For its part, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) published the results of its 2017 Armed Conflict Study, which places Mexico as the second country with the highest number of deaths (23,000 in 2016) after Syria (50,000), and before Afghanistan (17,000) and Iraq (16,000). It argued that the levels of violence stemming from the fight against organized crime in Mexico reached those of a country in open war. The Mexican State criticized the report questioning both the figures it handles and the fact that “violence related to organized crime is a regional phenomenon.”

In April, the Torture Law, which was under discussion for almost a year in the Chamber of Deputies, was approved, while “according to figures obtained by the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights, the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic received 4,055 allegations of torture, and reported that only 1,884 cases are under investigation. Of these, only 11 were registered, and only five sentences are known for that crime.” The Mexico Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights welcomed this law, as it completely forbids torture, “sanctions its conduct throughout the country under the same definition consistent with international treaties, excludes evidence obtained through torture … and establishes clear rules to combat impunity.” For its part, AI considered that it is a step forward but that “unless the Mexican authorities make a real effort to ensure the prosecution of all those responsible for the thousands of cases of torture reported each year (…), this law will be nothing more than words on paper. “

Another cause for concern regarding human rights: since last December, the Secretary of National Defense (SEDENA in its Spanish acronym), General Salvador Cienfuegos, has put pressure on legislators to pass an Internal Security Law. Similarly, Donald Trump’s threat of sending troops to Mexico to fight organized crime fueled the debate in favor of its approval. However, in February, the Chamber of Deputies decided to temporarily suspend the approval process, while human rights organizations have continued to join in the refusal to normalize the presence of the Armed Forces in public security tasks, given the evidence of abuses against the civilian population (see Focus).

Rising Violence against Journalists

Protest in front of the Ministry of the Interior a day after the murder of Javier Váldez © Noé Pineda Arredondo

The whole period was marked by the worsening violence against journalists, Mexico being the second most violent country in the world for this profession. In March, the killings of Cecilio Pineda Birto (Guerrero), Ricardo Monlui Cabrera (Veracruz), Miroslava Breach Velducea (Chihuahua) were recorded, as well as an attack on Armando Arrieta (Veracruz), and an attack against Julio Omar Gomez in Baja California, in which his bodyguard died. In May, seven journalists were ambushed by about 100 armed men while covering the operation that federal and state authorities initiated in San Miguel Totolapan, Guerrero. They were threatened, stripped of their work equipment, cell phones and one of their vehicles, and also beaten. In May, Javier Valdez was murdered in the capital of Sinaloa.

In March, the Washington Office for Latin America (WOLA) stated that the protection mechanism for human rights defenders and journalists from the Ministry of the Interior and all the country’s judicial institutions “have not been sufficient to prevent attacks against Journalists and defenders nor to meet their needs for protection and (…) impunity for these cases and for previous attacks and crimes perpetuates and aggravates the cycle of violence.” WOLA stated that “the government has to give more than empty promises, generic statements and justifications.”

CHIAPAS: Another critical scenario of human rights

In February, Silvia Juarez Juarez, a member of the Movement in Defense of the Zoque Territory, was arrested in Tuxtla Gutierrez, accused of the crimes of mutiny, criminal damage and kidnapping – allegedly against municipal officials – in the context of a protest in which she did not participate. She was released in March after being held for 35 days. The Zoque zone has been developing a process of resistance against hydrocarbons and mining projects in the municipality of Tecpatan, projects of more than 80,000 hectares under tender. Zoque organizations have denounced the flaws of their supposed “consultation” as well as the constant conditioning of government support to influence it. It is also worth noting that “the municipal president of Tecpatan, Armando Pastrana Jimenez, filed an injunction for the withdrawal of the PGJE to prevent the community defender from leaving prison” and maintained his complaint against 29 other defenders.

In April, the Samuel Ruiz Committee for the Promotion and Defense of Life expressed concern “at the strategy implemented by mining employees to confront campesinos of the Ricardo Flores Magon ejido, municipality of Chicomuselo”, which, by no coincidence, “is located on the road that leads to Ejido Grecia of the same municipality, and is the place where until 2009 the Canadian Black Fire [company] was extracting the mineral known as barite.” The Committee said that about 70 people were offered gifts, money and promises to build social works in exchange for a permit. He recalled that the communities “have organized as civil society to carry out surveillance operations to stop the entry of mining companies, so that accepting the proposal would be promoting a confrontation between campesinos that could result in a bigger problem.”

María de Jesús Espinosa de los Santos: spokesperson for the protest movement of the Dr. Rafael Pascacio Gamboa Hospital, press conference “Health crisis and Violence towards women”, May 2017 © SIPAZ

In April, nine nurses from the Dr. Rafael Pascasio Gamboa Hospital in Tuxtla Gutierrez held a hunger strike (lasting for ten days in some cases), which they lifted after reaching a series of agreements with the state government regarding their demands, which included the payment of labor benefits, the reinstatement of 15 workers unjustifiably dismissed and the supply of medicines in the 1,200 clinics and hospitals of the state. The Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Center for Human Rights, (CDHFBC), also denounced that the crisis in the health system in Chiapas is “a historical and structural problem, which has affected not only the workers in this sector, but also people who go to hospitals and clinics in the state.” On May 1st, the nurses resumed their hunger strike, after concluding that the draft agreements had not been met.

In May, Felipe Arizmendi, bishop of the Diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas, reported that the San Martín de Porres migrant shelter in that city was burgled. He indicated that there have been documented burglaries in houses for migrants of the diocese of Palenque, Salto de Agua, Comitan and Frontera Comalapa.

In a victory against impunity, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights determined the responsibility of the Mexican State in the case of the extrajudicial execution of Gilberto Jimenez Hernandez in February 1995 in La Grandeza community, municipality of Altamirano “within the framework of the implementation of the counterinsurgency strategy designed within the Chiapas Campaign Plan 94.” The CDHFBC stressed that “to date, the military jurisdiction has served to ensure impunity. The investigations of the present case have been framed in the lack of due diligence to cover up the Mexican Army.”

Chenalho: worrying parallels with the escalation of violence in 1997

The post-election dispute in the municipality of Chenalho claimed the lives of two people between February 22nd and March 7th, resulting in more than a dozen wounded from gunshots. Since the beginning of 2016, protesters have held demonstrations that led the mayor, Rosa Perez Perez, of the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM in its Spanish acronym), to apply for a license for the post. The local Congress appointed the municipal trustee, Miguel Santiz Alvarez, as substitute mayor. However, last August, the Electoral Tribunal of the Judiciary of the Federation (TEPJF in its Spanish acronym) ordered the reinstatement of Rosa Perez, which could not be implemented but she dispatched from San Cristobal de Las Casas where she received the official resources that correspond to the municipality.

On the morning of February 22nd, hundreds of supporters of Rosa Perez took over the town hall that sympathizers of the substitute mayor were guarding. The takeover of the building and a subsequent confrontation left one dead, 16 injured, vehicles destroyed and houses looted. Testimonies refer to the use of high-caliber firearms and “bullet-proof vests”. Later the body of Lorenzo Santiz Alvarez, son of the substitute mayor of Chenalho was found.

In this context, the parish of Chenalho recalled how the Acteal Massacre came about almost twenty years ago: “history seems to be repeated: acts of violence, threats, deaths and injuries, displaced persons, burned houses, armed groups, weapons.” They complained that “the authorities do nothing to solve the problem.” The conflict has so far caused more than 200 displaced persons and four deaths: “It is public and notable that in the municipality armed groups have reactivated and are acting with total freedom and impunity.”

No reduction in violence against women despite the Gender Violence Alert

Pilgrimage of the women of the Civil Society Las Abejas, municipality of Chenalhó, March 8, 2017 © SIPAZ

In March, the Women’s Group of San Cristobal Las Casas A.C. (COLEM in its Spanish acronym) noted that in 2016, 138 women died due to violent death, 89 cases being classified as femicides. According to the National Citizens’ Observatory of Feminicide (OCNF in its Spansih acronym), Chiapas is in tenth place in the Mexican states with the largest number of attacks on women registered.

In April, more than five months after the Declaration of Alert on Gender Violence (AGV), the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Feminicide in Chiapas reported that “despite the commitments made by the state government institutions and Federal government for the implementation of immediate actions to address the AGV, we point to the lack of commitment in clear and forceful actions to address the multiple complaints presented over acts of violence and femicide towards women.” It reiterated that “The partial declaration of AGV for 23 municipalities omits the serious violations of the human rights of women that are being committed in the other municipalities of the state.”

Initiatives and consolidation of other proposals

Recordando la masacre de Acteal el 22 de diciembre de 1997 (@SIPAZ archivo) Remembering the Acteal massacre on December 22, 1997 © SIPAZ archives

In March, Las Abejas Civil Society Organization launched the “Acteal: Roots, Memory and Hope” Campaign, which will be held this year in the framework of the 20th anniversary of the Acteal Massacre and the 25th anniversary of the foundation of the organization.

In April, the II Forum in Defense of Mother Earth and Territory was held in Santa Lucia, municipality of Ocosingo. Participants agreed to continue their struggle and ratified their rejection of the presence of the environmental gendarmerie in their territories. They reaffirmed “we will not allow evictions, nor any project imposed outside the interest and decision of the communities”; and recognized that they can “build community governments.”

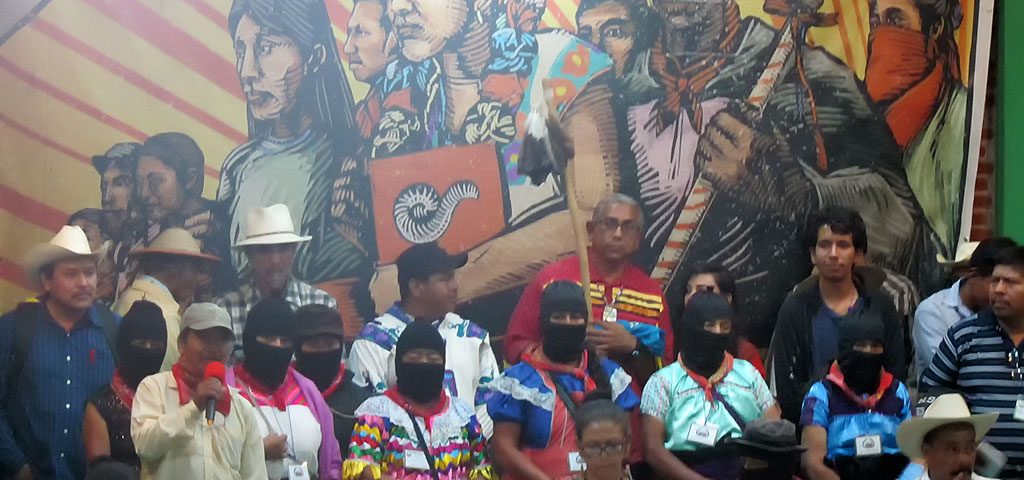

In April, the Critical Reflection Seminar “The Walls of Capital, the Cracks of the Left” was held in San Cristobal de Las Casas, an initiative convened by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) (see Article). In May, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI in its Spanish acronym) and the EZLN held the Constitutive Assembly of the Indigenous Council of Government (CIG in its Spanish acronym) in San Cristobal de Las Casas. 71 councilors were elected and Maria de Jesus Patricio Martinez, 57, a Nahua native from Jalisco and a traditional doctor was appointed as spokesperson. She will be an independent candidate to the presidency of the Republic in 2018.

OAXACA: Insecurity and impunity

In May, more than 50 organizations called on the government to act on rising insecurity in the state. They noted that official figures do not reflect the scope of the issue. They indicated that “Unfortunately these events have been normalized in society (…) without there (…) being a clear comprehensive strategy from the different levels of government to improve the living conditions of the population.”

On the other hand, threats, attacks and defamation continue to be recorded against human rights defenders. In March, Father Alejandro Solalinde Guerra, a migrant defender, was threatened with death through of a YouTube video.

Rodrigo Flores Peñaloza and Bettina Cruz Velazquez of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory (APIIDTT in its Spanish acronym) and the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of the Territory (APOYO in its Spanish acronym) reported surveillance, threats and defamation in recent months. Several antecedents could explain these facts: “it coincides with the intense mobilizations carried out to demand the clarification of the murder of Jose Alberto Toledo Villalobos from Chahuites, defender of the human right to electrical energy (…); as well as the active support for the defense of Cerro Iguu carried out by the Zapotec indigenous communities (…) of San Blas Atempa, against the construction of the electrical substation of SEDENA. Also noteworthy is the recent presentation of the collective injunction [amparo] (…) against the appointment of the region as a Special Economic Zone, the second phase of wind projects and mining concessions.”

These are examples of the processes of defense of land and territory that have resulted in threats. In May, the United Peoples Coordinator of the Ocotlan Valley (COPUVO in its Spanish acronym) also reported harassment when it sought to hold a forum against mining in San Jose del Progreso, “where for eight years they have defended their territory against the San José mining project.” It reported that the municipal president “publicly threatened our organization, communities in the region and civil organizations” proposing not to “not allow people to enter for a forum.”

Another issue that has resulted in attacks on defenders is linked to the police repression on June 19th, 2016, against a blockade in rejection of educational reform, which killed eight people and caused at least 226 civilian injuries. In March, the Committee of Victims of Nochixtlan for Justice and Truth June 19th (COVIC in its Spanish acronym) denounced “an attempted homicide” against its president, Santiago Ambrosio Hernandez, who was wounded. In April, Arturo Peimbert Calvo, head of the Oaxaca Human Rights Ombudsman (DDHPO in its Spanish acronym), reported that when he was in the vicinity of Nochixtlan, he was shot at at a long distance with gunshots to his vehicle. He noted that in the Nochixtlan case, “the lack of progress in the investigation favors impunity, and encourages aggression against the victims, relatives of deceased persons and their defenders, which is why it is necessary to make visible the delay with which the authorities are acting to start the investigations.”

Guerrero: Omnipresent violence

Demonstration for the appearance with life of the 43 disappeared of the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero © SIPAZ archives

In February, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center denounced the escalation of violence in Guerrero “where visible power is absent and, on the contrary, complicit in criminality.” It claimed that the State is no longer serving or protecting the population, but rather the interests of large transnational corporations and organized crime, both linked to each other, creating “an environment of fear that puts people in a state of extreme vulnerability.” It stated that the development model is “embedded in the dispossession and privatization of strategic resources” while seriously deepening social inequality. In addition, it noted that “they disappear and violently attack those who oppose such truculent businesses.”

For example, a judge found that Arturo Campos, a member of the Regional Coordination of Community Authorities – Community Police (CRAC – PC in its Spanish acronym), did not commit the crime of kidnapping that he was was charged with more than three years ago. Tlachinollan considered that “on the road to the search for justice, a step has been taken to show not only innocence but also the techniques of the State to criminalize the model of community justice of the CRAC-PC.”

In the February bulletin previously mentioned, Tlachinollan also blamed the security forces and the army for being “unable to contain this institutional disorder.” It is worth mentioning that in Guerrero, the person in charge of Public Safety and Civil Protection since 2014 is Brigadier General Pedro Almazan Cervantes. It is also the state of Mexico with the highest military presence since the years of the Dirty War. Nevertheless, according to the Mexico Peace Index of the Institute for Economy and Peace, in 2016, Guerrero was, for the fourth consecutive year, the most violent state in the country.

It is also of concern that the most covered case of human rights in Guerrero, the disappearance of 43 students of the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa (2014), continues without progress. In April 2017, the Follow-up Mechanism of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) noted “the lack of speed in reaching conclusions.” It said that “the issuing of public statements by high authorities that validate the hypothesis that the 43 students were cremated in the municipal garbage dump in Cocula is of concern to the Commission.” According to reports from the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (IGIE), “the minimum fire necessary for the combustion of 43 bodies was not scientifically possible given the evidence found.”

In April, the families of the disappeared were violently evicted from the premises of the Ministry of the Interior with tear gas. They were waiting to be seen by the Secretary of the Interior, Miguel Angel Osorio Chong, to know and demand advances in the investigations.