SIPAZ Activities (From mid-November 2018 to mid-February 2019)

13/03/2019

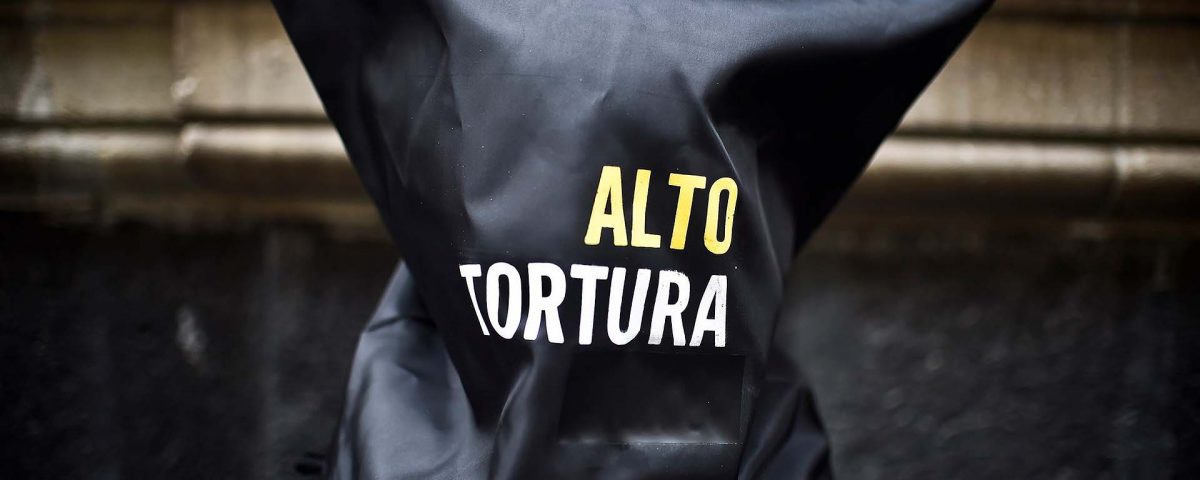

FOCUS: Torture in Mexico, an “endemic” and “generalized” problem

22/06/2019Both during the electoral campaign and after his victory in 2018, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) promised a great transformation of Mexico.

Six months into his term of office, he maintainsan approval rating above 60%, largely due to cuts in spending by different state structures, some reforms and a wide range of programs for the poor, among other factors. However, some analysts have pointed out several elements of continuity with previous administrations, among other concerns. For example,a key element of his campaign was the fight against corruption but no prosecution has been initiated against public officials or businessmen on charges of corruption. Furthermore, according to Mexicans against Corruption and Impunity, more than 70% of the present government contracts were awarded without bidding.

As for security, the creation of the National Guard was approved, a police force that will have 150,000 members, after making important changes to the initial proposal. The military component of the proposal had raised strong questions both in Congress and from sectors of human rights organizations. Among the main changes, it was established that the National Guard will be of a civil nature, that if its members commit a crime, they will be judged by civil authorities, and that the military personnel currently deployed in public security tasks will remain in the streets for no more than five years, while the National Guard is being formed..

More than 50 civil organizations, academics and activists warned about the possibility that “the only civil thing about this guard will be its administrative disguise.” They asked AMLO to fulfill his campaign promises and “no longer insist on militarizing the country.” “It should already be clear that military structures have not served or will serve to address situations of public insecurity”, they said. However, AMLO confirmed that the command of the National Guard will be a military official, along with its staff. He stressed that the National Guard will go through a process of training in human rights and “moderate, regulated use of force.” By May, the first 61,000 soldiers of the National Guard (of the armed forces and the Federal Police) had already been deployed without the approval of secondary laws that define the overall functioning of the new body.

Human rights: levels of violence and human rights violations continue to worry multilateral organizations

At the conclusion of her visit to Mexico in April, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), Michelle Bachelet, said she was surprised at what she found. “Without a doubt, the case of Ayotzinapa is well known by the press, but the 40,000 disappearances was not something that was so clear, the 26,000 unidentified bodies. Or that ten women are murdered every day. I knew very well about the violence, but I had no idea of the scale.” She pointed out that Mexico has a number of violent deaths similar to that of a country at war: 252,538 since 2006. She also signed a collaboration agreement on the National Guard and for the investigation of the forced disappearance of the 43 student teachers from Ayotzinapa (Guerrero, 2014). She stressed that the new authorities of the country “have recognized that Mexico has a human rights crisis” and that there is political will to move forward with the pending issues.

Many of these realities were inherited from previous administrations. Illustrative of this, in March, the Mexican government accepted 262 of the 264 recommendations issued by the UN Human Rights Council in the context of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), in addition to announcing that it will create a platform to process more than 2,800 international recommendations that the country has received since 1994.

An endemic theme in the recommendations is that of torture. In April, the “Alternative Report of Civil Society Organizations of Mexico” was presented before the United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT) to assist in reviewing the application of international agreements regarding the prevention, prohibition, and sanction of torture. The Mexican government questioned this diagnosis, which states that the practice of torture in the country is “generalized” considering that “it has decreased in the last two years.” However, it acknowledged that the problem remains “difficult and critical”, particularly at the state level. The CAT issued 98 recommendations that the Mexican government agreed to work on (see Focus).

Another issue that has marked the human rights agenda of the last two presidential terms of office is that of disappearances. In April, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH in its Spanish acronym) acknowledged that, “the disappearance of people in Mexico has not stopped and on the contrary, continues to increase throughout the country, with about 30,000 missing persons, 1,306 clandestine graves found and 3,760 bodies or remains found to date.” The new government has announced that an initial budget of more than 500 million pesos will be available. Advocacy groups made up of victims’ relatives have insisted on the creation of a Special International Mechanism on Forensic Identification and for the UN Committee against Forced Disappearances (CED) to analyze individual cases, among other demands. The Undersecretary of Human Rights, Alejandro Encinas, believes that there is no need for a new mechanism of international assistance and announced actions such as updating the National Registry of Missing Persons and the integration of the National Registry of Graves.

A less visible issue but of increasing presence at the national level, in April, in the absence of a General Law of Internal Displacement, a motion was approved to categorize as a crime Internal Forced Displacement (IFD). The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the matter called for “recognizing the phenomenon of internal displacement, making a diagnosis and collecting data on the different types of this problem in Mexico.” They urged to “develop and implement a specific law and public policies, (…) that have sufficient resources.”

Increased vulnerability of human rights defenders and journalists

Some worrying tendencies have been emerging since the change of government. In February, 166 organizations called on AMLO to consider that “the assessment and generalization” that he has made about organized civil society, as well as comments attacking its ethics and commitment, is “wrong and unjust.” On more than one occasion, Lopez Obrador has expressed criticism in this regard and announced that no civil organization would receive money from the public budget.

Regarding freedom of expression, in March, the organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) warned that Mexico continues to record numerous acts of violence against reporters, ranking 147th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index. In the first months of the AMLO government, ten reporters were killed. For its part, Articulo 19 noted that stigmatizing statements made to the press by the president can “legitimize and encourage attacks against journalists digitally, physically and affects the plurality of public debate. This increases the level of vulnerability and risk faced by journalists in the most dangerous country to exercise freedom of expression in the Americas.”

In March, AMLO and the undersecretary of human rights, Alejandro Encinas, presented their diagnosis of the protection mechanism for journalists and human rights defenders. Encinas recognized several deficiencies of the mechanism, among them, its bureaucratic and reactive nature. He also questioned why the body in charge of operating the mechanism is a private company. He said that its services will be maintained but “under a much more direct control and monitoring mechanism” until the State can assume this responsibility. SCO Space (Espacio OSC in Spanish) regretted that the “ineffectiveness” of the Mechanism was recognized “after 114 days of government”, and “after the murder of at least 15 human rights defenders and journalists.”

Megaprojects and rights of indigenous peoples

Demonstration of the National Indigenous Congress in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, April 2019 © SIPAZ

In April, to mark the 100th year anniversary of the death of Emiliano Zapata, in Chiapas, approximately 3,000 members of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI in its Spanish acronym) marched in San Cristobal de las Casas. They denounced that the president’s development plan “brings dispossession and destruction of our territories”, with projects such as the Maya Train, which, they warned, “will not happen, whatever the cost (…) even if they are thinking of doing it with their National Guard.” They stated that the new authorities “are the same foremen who want to impose death plans with their lying and rigged consultations.” In April, the National Fund for Tourism Promotion (FONATUR in its Spanish acronym) published the bidding rules for the basic engineering of the Maya Train, a project that will connect several tourist sites in the southeast of the country. It was opened without having carried out an environmental impact study or consultations with indigenous populations. AMLO affirmed that it is valid to begin this process, without taking into account these factors “because the citizens do want the train to be built” and that “in democracies it is the majority who decide, the minorities are respected, but it is the majority opinion that should have the possibility to decide in the end.”

Another controversial project is the Trans-Isthmus Corridor, which proposes, connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, similar to that of the Panama Canal. If carried out, it would include the rehabilitation of railways and refineries, the expansion of roads and the modernization of ports and airports, as well as the creation of “free zones” to attract private investments. Civil organizations questioned that “there have been no legally adequate mechanisms to guarantee self-determination, autonomy, environmental governance, and transparency in the decision-making of indigenous peoples over their territories. On the contrary, as the United Nations has pointed out in recent days, the consultations carried out by the federal government seemed to be rituals of political legitimacy, but not a legal act.” The CNI rejected: “the supposed consultation that the ‘bad governments’ intend to carry out in various communities of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec on March 30th and 31st. We denounce the corrupt practices that the ‘bad governments’ through the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples have been carrying out to seek to divide, deceive and intimidate our communities.” Other organizations in Oaxaca also rejected these Assemblies and the haste with which they were held, rather than “the times, uses, customs and forms of decision making of the communities, as well as their representative bodies.”

Demonstration of the National Indigenous Congress in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, April 2019 © SIPAZ

On the government side, Adelfo Regino Montes, in charge of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI in its Spanish acronym), affirmed that international standards were respected and that “in a second stage, specific consultation processes will be carried out in cases of direct effects to lands and other fundamental aspects of the life of indigenous communities.”

International: Unprecedented immigration crisis

The flow of Central American migrants to the United States has multiplied since last year with the formation of caravans coming mainly from Central America. Since coming to power, the new government opted to provide one-year “humanitarian” visas that would allow its beneficiaries to work and live legally in Mexico. More than 15,000 were awarded. However, by February, the Mexican government decided to “order” the migratory flows and the number of visas fell from more than 11,000 in January to about 1,500 in March. It began to prioritize the delivery of “regional visitor cards”, which limit mobility to four states in the southeast of the country. The new type of visa aims to prevent more migrants from concentrating on the northern border, andalso to obtain labor for the construction of megaprojects in the southern part of the country.

Meanwhile, deportations of migrants from Mexico have skyrocketed. The number of expelled persons has almost tripled between December and April, according to the National Institute of Migration (INM), representing approximately 45,370 people and saturating the capacity of detention centers. Neither US President Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant speeches nor actions on the Mexican side have reduced pressure on the US border, where 98,977 people were arrested in April, the highest monthly figure since 2007.

In May, the Collective of Observation and Monitoring of Human Rights in Southeast Mexico said that the beginning of migrant caravans has substantially modified “the conventional migratory pattern of dispersed and invisible human mobility, individual or in small groups, transmuting it into a collective, public form”, which also “exposed the ineffectiveness of migration control policies.” They denounced that neither the previous nor the current government has been able to provide comprehensive responses to the needs. They mentioned the implementation of “short-term measures, with limited clarity and transparency.”

Chiapas: human rights issues beyond the migration crisis

A point of renewed concern in Chiapas has been militarization. In May, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Human Rights Center reported that the military carried out acts of espionage during a meeting of land rights activists in Chicomuselo. It also stated that it had “registered different acts of intimidation and harassment against defenders (…) who organize themselves in defense of Mother Earth given the reactivation of mining projects in the region” since January. Earlier this month, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Human Rights Center also reported that “since December 2018, the Mexican state increased the militarization to territories of Indigenous Peoples’ Support Bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (BAEZLN in its Spanish acronym) especially in the Lacandon Jungle region as part of the continuation of the counterinsurgency strategy to erode autonomy projects in Chiapas.”

Another issue of concern continues to be the situation in several municipalities in the Highlands of Chiapas. In May, civil organizations expressed their concern at “the actions of armed paramilitary civilian groups, perpetrators of forced displacements, disappearances and killings in the region.” They recalled that since February 2018, “the population of the municipality of Aldama is experiencing a humanitarian crisis” due to the forced displacement of 2,036 people. They affirmed that, “the Mexican State has not implemented sufficient and adequate measures to stop the violence.”

As for Land and Territory, in February, in the municipality of Solosuchiapa, thousands of people held a march to demand the cancellation of the “Santa Fe” Mine and that of all other mining concessions considering that “it will truncate the possibility of the development social, cultural, spiritual and other alternative ways of life.” In April, the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory (MODEVITE in its Spanish acronym) ratified its opposition to the construction of the San Cristobal de Las Casas – Palenque super highway. Pueblo Creyente (People of Faith) of 11 municipalities of the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas denounced that “looting is disguised with the construction of a super highway, saying it is a benefit for the people, but it has a direct effect on our brothers and sisters who depend directly on Mother Earth.”

Press conference of the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women in Chiapas, March 2019 © SIPAZ

Also in April, Oxchuc chose its new municipal government through a vote by show of hands. It was the first time that a municipality of Chiapas legally elected its government through customary measures. Two other municipalities in Chiapas, Sitala and Chilon are in a similar process.

In March, six prisoners in different prisons in Chiapas began a hunger strike demanding “justice and their immediate and unconditional release.” Seven more inmates later joined in solidarity. The Working Group “No Estamos Todxs” denounced that “the legal processes of these people are plagued by irregularities and serious violations of their human rights.” Although a process of dialogue with the state government began (in which the strikers decided to eat every third day), by May, six prisoners resumed their strike in the absence of progress.

In March, the Popular Campaign Against Violence Against Women and Femicide in Chiapas announced its evaluation of the Gender Violence Alert (GVA) two years and three months after its launch. The campaign declared that the GVA has “turned out to be a simulation and a mockery for the women who were raped and murdered. We also denounce that the authorities (…) have generated impunity and have shown indifference, negligence, ignorance and even complicity with the perpetrators.” They denounced that government actions “are so innocuous, superficial and insufficient that they have only vulgarized the concept of gender, showing not only the inability of the government to address the problem, but also the obtuse patriarchal character of the institutions.”

OAXACA: growing vulnerability for defenders and journalists

National trends in the increase of vulnerability of human rights defenders and journalists have been particularly noticeable in Oaxaca. In May, the human rights defender of Indigenous Women by Ciarena A.C, Silvia Perez Yescas, was the victim of new attacks despite being in the Federal Protection Mechanism for Defenders and journalists. In April, Juan Quintanar Gomez, adviser to indigenous communities in various agrarian conflicts, was attacked in the city of Oaxaca.

The Council of Autonomous Oaxacan Organizations (COOA in its Spanish acronym) denounced that, “despite our multiple complaints, mobilizations and demands before the corresponding authorities, there is no substantial progress in the cases of the five assassinations against CODEDI compañeros and three other assassinations against OIDHO, UCIO-EZ and APIIDTT compañeros.” It also noted that “arbitrary arrest is used and arrest warrants are issued to intimidate those who continue to have the courage to organize, social protest is criminalized and campaigns are financed to discredit the organized people in the media.”

In May, a year after the disappearance of human rights defender Ernesto Sernas Garcia, his relatives and militants of the Red Sun People’s Current (Corriente del Pueblo Sol Rojo) reported that the law enforcement agencies have been dedicated to “delaying and obstructing the search process.” Human rights experts from the United Nations also condemned the lack of progress. They considered that Red Sun continues to be the target of intimidation and attacks, an illustration of which is the murder of defender Luis Armando Fuentes in San Francisco de Ixhuatan in April. They urged “the Mexican authorities to address the underlying causes of violence against human rights defenders, in particular the adverse environmental and human rights impacts of megaprojects.”

The situation of the press is not much better. In March, journalist Jesus Hiram Moreno was wounded in Salina Cruz. He said he was convinced that it was not merely an assault, as one of his lines of investigation was corruption in Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX in its Spanish acronym). In April, he began a hunger strike when the investigation into the attack was closed without progress. In April, the reporter Ana Luisa Cantoral received death threats. She said she fears that the threats could “be related to her coverage of events that would show alleged irregularities within the Public Security Secretariat.” In May, Telesforo Santiago Enriquez, from the community radio station “El Cafetal” was also murdered.

GUERRERO: Endless crisis

Demonstration for the safe return of the 43 students of the Rural Normal School of Ayoztinapa in Guerrero © SIPAZ, Archive

In May, during a protest over the 43 students who disappeared from the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa in Iguala in 2014, it was reported that in “five months of the government of President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the Ayotzinapa case is still stuck because the FGR and SEDENA have no interest in resolving it.” The Office of the Attorney General of the Republic (FGR in its Spanish acronym) was urged to appoint a special prosecutor for the case and the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA in its Spanish acronym) to deliver the information about the attack it has in its possession.

If the most emblematic case of the state shows little progress, it is not surprising that other indicators continue to mark a highly critical context. Three defenders were killed in Guerrero between February and May: in April, Julian Cortes Flores of the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (CRAC-PC in its Spanish acronym) of San Luis Acatlan, was murdered, “an attack against the system of security and community justice of the peoples of the Coastal-Mountain region”, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center concluded. In May, the CNI denounced the kidnapping and murder of councilor Jose Lucio Bartolo Faustino and of the delegate Modesto Verales Sebastian “by narco-paramilitary groups that operate in the region with the complicity and protection of the three levels of the bad government.”

Another illustration of the extreme vulnerability of defenders in the state, in March, the ex-political prisoner and founder of the CRAC-PC in Tixtla, Gonzalo Molina Gonzalez, “suffered three kidnapping attempts despite having the protection mechanism for defenders and journalists granted by the Mexican State”, while participating in a march in Mexico City.

Another indication of aggression and control towards defenders in the state is the use of the justice system. Since December, meetings have been held between social and civil organizations and the state government to review the cases of several prisoners, as well as to demand the end of harassment against members of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to La Parota Dam (CECOP in its Spanish acronym). The authorities have said that the legal route will be given preference. Tlachinollan believes that “the public prosecution obtained through torture, arbitrary arrest and isolation, several pieces of evidence with which they have been brought to trial. The real reason for their arrest is to stop their historic fight against the construction of La Parota hydroelectric dam.”

Another issue that gained greater attention is that of internal forced displacement. For 39 days around 350 people, representing a little more than a third of the families that were displaced from a Zitlala community and eight from Leonardo Bravo since last November, due to the presence and threats of an organized crime group, held a protest in front of the National Palace in Mexico City to demand attention to their demands. They decided to return to Guerrero after signing an agreement with the government.