URGENT BULLETIN – Reactivation of the agrarian conflict between Chenalhó and Chalchihuitán: generalized violence and impunity

21/12/2017

FOCUS: THE EARTH CANNOT TAKE ANY MORE

11/01/2018On September 7th, shortly before midnight, there was an earthquake with an 8.2 magnitude on the Richter scale and with an epicenter in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, 143 kilometers southwest of Pijijiapan, Chiapas. The biggest damages were reported on the Chiapas coast and the Oaxaca area. On September 19th, there was another earthquake with a magnitude of 7.1 degrees that severely affected the center of the country (Morelos, Puebla, the State of Mexico and Mexico City).

Child playing in the middle of the reconstruction works. Civil Observation Mission to the Coast after the September earthquakes © SIPAZ

According to official reports, the number of victims was 98 dead due to the earthquake of 8.2 and 369 following the earthquake of 7.1 (225 of them in Mexico City). There were total and partial damages in homes, schools, hospitals, churches and historic buildings with preventive suspension of classes in several states. The statistics have been changing and have been sources of controversy but we are definitely talking about more than two million people affected.

Another of the victims of the earthquakes has been access to information in long days of chaos. The organization for freedom of expression Artículo 19 denounced that “there is no justification for this limited and restricted response (…), the government communication has focused, once again, on promoting the image of the President of the Republic, other high officials and institutions in locations of disaster.” Media also reported tensions between authorities and citizens in rescue situations, as well as alleged political use of aid and reconstruction plans. It was also stressed that, with an earthquake ten times smaller than in 1985, the number of victims and damages in Mexico City indicated a lack of significant improvement in planning and prevention in new and old buildings. However, in the face of tragedy, a source of hope has been the solidarity of and in civil society (See Article).

NAFTA, Bleak Renegotiation

Donald Trump and neoliberal model vs. Mexican people, Analysis space at the Encounter of the Pastoral of Mother Earth, September 2017 © SIPAZ

On another note, a renewal of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, the United States and Mexico (1994) is still under negotiation. Several articles have been published about the results of the first stage. In the Mexico of the nineties, integration into the largest trading bloc in the world was presented as an opportunity to promote economic growth, the creation of jobs, an improvement in salaries and social welfare. 23 years on, the results are -at least- mitigated.

Certainly, Mexico became an exporting power, not only of oil but also of manufactured goods, of products of the automotive and agri-food sectors. Starting outside the top 30 countries with the largest foreign trade in the mid-nineties, it rose to number 13 worldwide. However, it seems that little has served that foreign trade has grown at an annual rate of between 10% and 12% when, in the same period, the economy did so by only 2.5%, less than before the treaty. It should be recognized that the Mexican export industry is concentrated in a few hands. Meanwhile, the socioeconomic indicators have not taken off in terms of salary, jobs, social benefits or poverty.

Otherwise, the prospects for renegotiation are low when the United States plans to reduce the trade deficit it has with Mexico at any cost, a campaign promise of President Donald Trump. There is no clarity on when this process ends or on what terms. Neither whether Mexico considers alternatives (such as the diversification of its economic partners or a modification of its economic model) in the face of risks of breach of the Treaty or resolutions that negatively impact on its economy. The presidential elections of 2018 already under way make the process even more difficult for Mexico.

2018 Elections, a contest that promises to be harder fought than ever

Formally, the electoral process began with the registration of those who aspire to participate as independent candidates in the presidential race. This figure was established more than a decade ago, supposedly to break the monopoly of political parties. It is the first time that it could make a significant difference in the process and its results. There are many applicants who are gathering the necessary signatures to participate in the campaign.

Some analysts question if it is becoming another option so that “the usual” (powers and economic interests) remain in power without bearing the loss of prestige of the political parties. Some others point out that, intentionally or not, it will have an impact on the fragmentation of the opposition vote of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI, party currently in power and which has been so for more than 70 years with only one interruption between 2000 and 2012). ). It is estimated that with nine or ten candidates for the presidency, the PRI could win again with its “hard vote”.

Human Rights: Unending List of Unresolved Issues

Press conference in Chiapas in the framework of the visit of the Special Rapporteur of the United Nations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Mexico, November 2017 © SIPAZ

In October, the Legislative Power finally approved the General Law on Enforced Disappearance after three years. National and international organizations welcomed the decision and called on the legislators to provide it with a sufficient budget, and the President to publish it immediately. They stressed that deficiencies remain: the lack of a register of victims, the impossibility of investigating and punishing commanders who order their subordinates to illegally detain a person, as well as the absence of an independent forensic institute.

The situation of human rights defenders and journalists continues to be a matter of concern. In September, the Cerezo Committee published the Sixth Report of Human Rights Violations against Human Rights Defenders. It documents that “every day there were four violations of human rights against defenders.” It reports 2,426 arbitrary detentions, 123 arbitrary executions and 11 forced disappearances since Enrique Peña Nieto’s six-year term of office began. The report states that, “the improvement of repressive techniques includes actions such as maintaining impunity (…) which implies that the State covers the gaps in investigations of the most serious cases (…) to prevent them from reaching international bodies (…). At the same time, it accepts the visits of international bodies of HR, but disqualifies the reports that they make (…). It further discredits the defense of human rights (…): allowing a campaign that equates human rights defenders as defenders of criminals and, (…) strengthening international humanitarian law, which judges people and not state structures, adducing that the HRV [human rights violations] are individual acts, of infiltrated or stressed subjects, but that there has never been an order from the structures of the state.”

In November, the Washington Office for Latin American Affairs (WOLA) published “Forgotten Justice: Impunity for human rights violations committed by soldiers in Mexico.” It denounces that “soldiers who commit crimes and human rights violations generally do not answer for their actions, neither do the public officials who request the presence of soldiers in their states or municipalities, nor the political leaders who for decades have not really committed themselves to improving the police in Mexico.” It stands out that of the 505 cases registered between 2012 and 2016, only 16 accused have been convicted by the civil justice system. The report affirms that, “more than ten years of a strategy of security and fighting against organized crime based strongly on the deployment of the military and on the use of force but not on justice have passed in Mexico.” The impunity factor is not limited to military settings: the Global Impunity Index 2017 states that Mexico ranks 66 out of 69 countries studied, surpassed only by the Philippines, India and Cameroon.

Finally, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, made an official visit to Mexico in November, which also included the states of Guerrero, Chiapas and Chihuahua. At the end of her visit, she declared that, “the current inadequate legal recognition of indigenous peoples as holders of rights, together with structural discrimination, are the basis of all the issues and concerns.” Even recognizing “Mexico’s support for advancing the indigenous agenda in international forums”, “this commitment must be coherent and should be reflected in the application of these standards in Mexico.”

CNI: Candidacy Registration and More Harassment

The rapporteur also stressed that “the initiatives of indigenous peoples in the area of autonomy and self-government should enjoy greater recognition, and be recognized and incorporated into the overall political structure of the country. In addition to self-government, indigenous peoples have the right to participate fully, if they so wish, in the political life of the country. I have seen some positive developments that could facilitate the political participation of indigenous peoples in this area, such as the possibility of registering independent candidacies.”

In October, Maria de Jesus Patricio Martinez (Marichuy), an indigenous Nahuatl and spokesperson of the Indigenous Council of Government (CIG in its Spanish acronym), a representation and decision-making structure recently formed by the National Indigenous Congress (CNI), registered her candidacy before the National Electoral Institute (INE in its Spanish acronym). Later, she began a tour of the five Zapatista caracoles (autonomous regions) where she was received by thousands of people in each one. Part of the objective was to gather citizen support for the collection of 866,500 signatures in at least 17 states that will allow her to be accepted as an independent candidate. In this context, the CNI denounced that, “on October 18th, for at least five hours, the INE website was blocked [making] it impossible to carry out any kind of auxiliary registry operation or to review the progress of signatures or signature register. During the sessions and tours, access to telephones and the Internet was blocked in the municipalities of Altamirano and Ocosingo, places where these services usually work well.” There was also a series of acts of harassment and surveillance during her tour of the coast of Chiapas in September.

Two situations of threats and attacks against members of the CIG in Chiapas in the last three months were also reported: in September, the councilor of the CNI of the northern jungle region (municipality of Tila) was threatened with kidnapping and murder, and in October, the home of Guadalupe Nuñez Salazar, Councilor of the CIG, was ransacked.

CHIAPAS: Social Conflicts without attention to first electoral uncoverings

In Chiapas, 2018 will be an election year not only to elect the new president but also for the position of state governor. In August, the Movement in Defense of Life and the Territory (MOVEDITE in its Spanish acronym) denounced “political groups disguised as civil associations or aid foundations, that use people and abuse their poverty. Where they condition the most basic aid by votes and thus corrupt those who they claim to support.” It also denounced “political propaganda on posters, painted walls and calendars that promote candidates outside the stipulated time.” It added that, “it is confirmed that the parties have not changed and will not change.” It should be remembered that MOVEDITE has a presence in 12 municipalities in Chiapas, and that it has been organized to strengthen community governments.

Disagreements between different visions of development continue. In August, the governor of the state of Chiapas, Manuel Velasco Coello, stated that everything is ready for the inauguration of the first Special Economic Zone of the country, one of the projects most questioned by the people at present. In contrast, in September, an encounter was held by the Diocese of San Cristobal in Candelaria, municipality of San Cristobal de Las Casas: “We congregate, enlightened with the word of God, and, currently, with the Encyclical Laudato Sí from Pope Francis, who calls on us to defend our Mother Earth facing the destruction and dispossession that the capitalist system exercises.”

In a similar vein, in October, a meeting was held in Grecia ejido, Chicomuselo as well as a pilgrimage called “Movement against mining exploitation and the dispossession of the Earth” in which some 5,000 people participated. In September, human rights organizations had already denounced that: “the reactivation of mining companies in that region of the Sierra Madre increased division in the communities, harassment and the risk of confrontation among its inhabitants.” They had also mentioned “the expulsion of a dozen campesinos, from the Ricardo Flores Magon community for not allowing mining companies to pass through that community”; and that those who participate in patrols to prevent mining companies from entering their communities were threatened with death.

Also in October, the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Femicide in Chiapas, stated its position almost a year after the Gender Violence Alert was declared for seven municipalities along with specific actions for 17 indigenous municipalities of the Highland region. It insisted that “it should be extended to the entire state of Chiapas due to the context of increasing violence against women.” It stated that “we have noted with concern that the representatives of the Government of Chiapas have politicized the Declaration to promote candidacies, strengthen political posts and justify redirecting public budgets.” It declared that “there are no concrete results and they lack a plan and programs that allow monitoring and evaluating the advances, challenges and setbacks in the implementation of actions.”

OAXACA: Earthquake Aggravates Pre-existing Situations of Inequality, Violence and Impunity

In September, a Humanitarian Aid Observation Mission (MOAH in its Spanish acronym) visited the communities of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec that were affected by the 8.2-magnitude earthquake in September, leaving 283 municipalities in Oaxaca affected. They noted that “the basic urgent needs of the people affected by the earthquake have not been met”; and that there is a “lack of governmental coordination in the distribution of humanitarian aid and the discretionary use of the scarce resources that have arrived.” They denounced that “potential candidates and public officials have fallen into opportunism by conditioning humanitarian aid by handing it over only to people close to the government and political parties, some even re-label and re-channel food.” They emphasized that “this crisis situation adds to the preexisting conditions of exclusion, inequality and poverty (…). Therefore, the MOAH emphasizes that faced with the serious disaster caused by the earthquake the affected people are holders of rights, NOT objects of help.”

Some progress was made regarding the issue of impunity in the last three months: in the case of Nochixtlan and as regards femicides. In October, the National Commission for Human Rights (CNDH in its Spanish acronym) issued a recommendation for serious human rights violations in the acts of repression and violence that occurred in Nochixtlan in June 2016, which led to seven people killed, 453 civilians with physical injuries, and 106 uniformed agents wounded. The CNDH accredited the excessive use of public force as a consequence “of an operation improperly designed, prepared, coordinated and executed, in which the protocols for action were not fully observed, particularly as regards the legitimate use of force and the need to prioritize the use of non-violent mechanisms and techniques.” The national ombudsman, Luis Raul Gonzalez Perez, reported that the investigation of almost 16 months was marked by lack of cooperation from the authorities involved, a sign of “the lack of will to know the truth and fine those responsible.” However, victims of Nochixtlan ignored this recommendation, considering that it “incriminates the victims and favors the aggressors.”

On another note, in October, a first sentence was issued for the crime of aggravated femicide, a sentence of more than 78 years in the case of the murderer of the youth Dafne Denisse. Since femicide came into force as a criminal offense in 2012, 477 femicides have been documented. However, only eight convictions for this crime have been obtained according to the Superior Court of Justice of the State. The National Citizen Observatory of Femicide (OCNF in its Spanish acronym) has indicated that the omission, delay, collusion and complicity of the authorities have fostered the prevalence of violence against women.

In other issues, in August, the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining convened the forum “Extractivism or Life” in Ixtepec City to “continue strengthening our organizational processes” and “to update the information (…) on the different megaprojects that are always chained together and that have reached their maximum expression of usurpation with the brazen definition of the Special Economic Zones (SEZ).” It regretted that governments “legitimize and allow voracity, looting, pollution, destruction and irreversible damage to health and the environment that the extractive model and its megaprojects cause.”

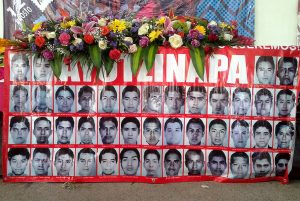

GUERRERO: The Ayotzinapa Case Three Years On

September 26th marked the third anniversary of the extrajudicial executions of six people and the forced disappearance of 43 students from the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa in Iguala. Marches were held in several states to demand an end to impunity in the case. Amnesty International Mexico warned: “Three years later, we continue to search for our disappeared among the rubble of corrupt institutions and the crime of oblivion, where the real political will of the authorities has never been present.” In October, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) pointed out that “not resolving an act of this nature in three years simply means that the federal government does not want to solve it.” The Tlachinollan Mountain Center for Human Rights stated that “the Mexican State continues to administer the case for political purposes unrelated to the victims’ desires for justice, given that in each hearing or meeting it drip feeds the information and the progress it presents” and is convinced that “the Office of the Attorney General covers up officials who obstructed the investigation.”

In September, the TdT Network announced the launch of an alert for human rights defenders in the state. As a first action, a civil observation mission was carried out in Chilapa and Chilpancingo. In their main conclusions, they pointed out that “the normalization of the military presence as well as forced displacement in different municipalities of the state is unacceptable.” Regarding the situation of families of victims of forced disappearance, they witnessed “the pain and impotence derived from the impunity and indolence of the authorities.” They also expressed their concern “for the stigmatization of defenders.”

In October the 22nd anniversary of the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (CRAC-PC in its Spanish acronym) was held in the municipality of Malinaltepec. In the closing, the CRAC PC reaffirmed its commitment to continue working towards networking in defense of the normative systems of community, territory, women’s rights, the disappeared and the violations of human rights in the country.

In November, four years after his arrest, a rally was organized in front of Chilpancingo prison, precisely to demand the release of several community policemen. At the end of her visit to Mexico, the UN Rapporteur for Indigenous Peoples recommended “strongly that in-depth discussions be held between the judicial bodies, the relevant Mexican authorities and the indigenous peoples in order to develop the necessary harmonization. This would include mechanisms to ensure that the exercise by indigenous peoples of their justice systems does not result in their criminalization.”

As in Chiapas and Oaxaca, we find the mining issue at the center of peoples’ concerns. In October, the National Meeting against the Mining Extractive Model was held in Malinaltepec, in which the participants ratified their “principle of persisting in promoting our own processes of Consultation and Prior, Free, Informed and Culturally Appropriate Consent, with which we send a clear message to the state, politicians and mining companies that in our community territory we will not allow them to violate our collective rights with false and rigged processes and consultation procedures.”