SIPAZ Activities (From mid-November 2019 to mid-February 2020)

06/03/2020

FOCUS: Gender Violence – Fighting Another Pandemic

03/06/2020In April, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) presented his fifth quarterly report. Facing the COVID-19 pandemic, he reported that this year there will be 22 million beneficiaries of the different social programs and that in nine months two million new jobs will be created, among others by the Sembrando Vida (Sowing Life) program.

He stressed that his government had already “made the decision to overcome the dilapidated state in which the public health system was left to us.” “This crisis is temporary, transitory, normality will soon return. We will defeat the coronavirus,” he declared. It should be remembered that the Mexican president was criticized internationally for his attitude towards the pandemic. While other Latin American governments began to implement isolation measures, Lopez Obrador called for “our lives as usual” to continue for several weeks, before implementing a confinement that has been more voluntary than mandatory. On May 21st, 60 days after the start of the “National Period of Healthy Distance”, Mexico reported 6,510 deaths from COVID-19, with which the country joined the list of the ten countries that with most deaths registered from the pandemic. It also had almost 60 thousand accumulated cases. Even so, it has already been announced that from June 1st, it will enter the “New Normality”, with a system of traffic lights that will be published for each region of the country.

Indigenous peoples, prisoners, migrants: highly vulnerable groups to Covid-19

In April, civil organizations made “an urgent call for sufficient staff and equipment to be provided to guarantee indigenous people quality care.” In addition, they demanded that a national plan to rescue community economy be put in place for those who cannot carry out their work due to confinement and that information regarding the pandemic be translated into indigenous languages. This last point was also one of the demands of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), this month.

In May, civil organizations reiterated their “deep concern about the conditions that the pandemic may generate in indigenous” communities. “In addition to the lack of infrastructure, medical personnel, and continuous supply of medicines, institutional discrimination and the lack of a culturally appropriate and affordable preventive approach to the communities are added; as well as, in this context, the lack of adequate monitoring and follow-up for returning migrants,” they denounced. Likewise, they were concerned about “the economic vulnerability of the majority (…). The lack of access to decent sources of employment in the communities makes them dependent on trade and informal employment, as well as on remittances from migrants,” sources of income that “are at risk of sharply declining.”

In March, civil organizations called for measures to be taken in prisons to prevent the spread of COVID-19. They recalled that “due to the close proximity conditions in prisons, incarceration generates the ideal conditions for contagion and these are aggravated when there is overcrowding, lack of water and hygiene conditions.” The CNDH also called for preventive measures to protect the life and health of persons deprived of liberty; of visits; of prison staff, and of service providers.

In this context, in April, an Amnesty Law was approved, through which people who have committed minor crimes could be released. It will not benefit “recidivists, people accused of homicide, kidnapping, serious injuries, violence or use of firearms, femicides, rapists, traffickers, huachicoleros or burglars.” It will also apply to indigenous people who have not been guaranteed “the right to have interpreters or defenders who have knowledge of their language and culture.” The Office in Mexico of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) urged “the rapid application of the law.” It also stated that “it is a positive step that must be framed in the discussion on the transformation of the Mexican justice system”, to review figures such as “informal preventive detention” and “a variety of penal types that lead to abuse of the prison sentence.”

In April, Human Rights Watch asked Mexico for the “immediate release of migrants if they can no longer be deported to their countries of origin or if they are in arbitrary detention,” in light of border closures and to prevent outbreaks of coronavirus in detention centres. It denounced that “thousands of migrants are being held (…) in inhumane and unhealthy conditions”, so it is not surprising that since March “people detained in five migrant detention centres in Mexico have started protests and have demanded their release” for fear of infection. There have been “clashes in which there were dozens of wounded and at least one dead,” it added. “It is absolutely imperative that the Mexican government act immediately to release or find alternatives,” it stressed. Mexico has taken no action in this regard.

Megaprojects: “essential” activities?

Since April 6th, AMLO decreed the suspension of work for non-essential activities due to the health emergency, but activities related to megaprojects were exempted. He ratified this position on April 22nd, when he released a series of guidelines contained in a decree to address the economic crisis caused by the pandemic. In addition to reducing the salary of senior officials and the operating expenses of government agencies, it raises the guarantee of the continuity of projects such as the Maya Train, the Dos Bocas refinery or the Felipe Angeles International Airport, oil production and social programs.

Given this, communities, activists and civil organizations called for the suspension of the construction of the Maya Train as it puts at risk “the health and life of the workers who will have to continue with the works (…) as well as the population, mostly indigenous, affected by it.” “It seems that the federal government is taking advantage of the current situation to advance, without the risk of opposition, in the continuation of a project that has been questioned by various sectors and whose opacity has even generated the issuance of a suspension order by a Federal Judge before an appeal filed by the communities of Calakmul and Candelaria,” they stated. They also requested that, after the emergency, “a real, serious, informed and equitable dialogue process be started that guarantees the rights” of indigenous peoples. They stressed that “the absence of information on the environmental, economic and social impacts that said work will entail has been insistently repeated.”

In May, a federal judge granted an injunction to indigenous people in Chiapas to suspend the works of the Train in the Palenque stretch, since “it would enhance the risk of the inhabitants of the Maya Ch’ol community of contracting the COVID-19 virus and by the same token, the possibility of being treated would decrease.” The National Tourism Promotion Fund (FONATUR) assured that it has not been notified and considered the provisional suspension inadmissible. Subsequently, the CNDH also made a call to stop the works because of the risk of contagion that the indigenous communities and workers involved face.

In the case of the Trans-Isthmus Corridor, more than 150 organizations requested the immediate cancellation of the Program. They spoke in favor of building an alternative proposal – based on reflection and horizontal dialogue. They denounced that the right to self-determination of indigenous and Afro peoples has not been respected. In addition, they foresee environmental impacts “if the new imposition of this set of megaprojects is allowed (…), pollution, health effects and global warming would become more acute, and the basic needs of the inhabitants and peoples of a large portion of the south-southeast would be compromised.” They recalled that “development” projects implemented on the Isthmus, “have not really benefited local populations; on the contrary, they have generated a severe deterioration in their ways of life, their cultures, the environment, the social fabric of the community, and have been affected by an increase in militarization.”

Invisibility of other pending human rights issues amid the pandemic

On March 8, International Women’s Day, Mexican women made history by holding marches and other types of demonstrations, achieving a never-before-seen call to demand greater equality and to protest against gender violence and femicides. In addition, after the invitation to a national strike for March 9th, with hashtags such as #ElNueveNingunaSeMueve, it is estimated that around 22 million women joined (see Focus and Article).

In March, the Mexican Centre for Environmental Law (CEMDA), presented a report in which it reiterated the danger for environmental defenders in Mexico. It noted that between January 2012 and December 2019, there were 499 attacks against environmental defenders and 83 murders. During 2019, the first full year of the AMLO government, 39 attacks occurred, 15 of them being murders. CEMDA stresses that: “no progress has been made in a structural change that generates the appropriate and safe conditions for the exercise of the right to defend human rights. Currently, we still find discourses and narratives from the government that disqualify and stigmatize the defense of human rights, which polarizes the perception of society, managing to delegitimize and create a hostile environment so that other attacks can be committed.”

On May 10th, Mother’s Day in Mexico, women demonstrated to confirm that they will continue to search for their missing children. The call was broad and, due to the pandemic, the protests took on other forms that included actions on social networks or caravans. Family organizations urged the government not to stop searching for the more than 61,000 disappeared, despite the contingency, and to speed up the identification of the more than 37,000 bodies that are unidentified so far.

Also, in May, a decree was published that will assign public security tasks to the Armed Forces for the next five years, in aid of the National Guard (GN), until it develops its structure, capabilities and implantation throughout the national territory. It is unclear who will have command of the military forces dedicated to these tasks. The group #SeguridadSinGuerra (Security without war) expressed its rejection of the decree, considering that “it has a series of gaps, among them the time and geographic scope in which the Armed Forces will act with public security powers, it does not contemplate accountability mechanisms nor does it guarantee that the armed forces are subordinated to a civilian power.”

CHIAPAS: a health sector that can easily be overwhelmed

In mid-March, before the government measures, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) announced the actions it will take in the face of the pandemic, including a complete closure of its autonomous structures and a call for confinement for its support bases. It invited the general population “to take the necessary sanitary measures that, on a scientific basis, allow them to survive and survive this pandemic”, without “dropping the fight against femicidal violence, (…) in defense of the territory and Mother Earth, (…) for the disappeared, murdered and imprisoned and (…) for humanity.”

In April, organizations in Chiapas asked the government: “to see to the social determinations of the pandemic that place migrant populations, working children and street children, residents of urban peripheries, people in detention, precarious workers as sectors with greater vulnerability to contagion, timely diagnosis and access to treatment.” In the case of indigenous peoples, they demanded “to fully respect the exercise of their right to autonomy and their own models of health care.” The health emergency “highlights the dismantling of public health systems,” they denounced. They urged that “under no circumstances should measures of force be applied from the police and military bodies for the purpose of containing the population.”

Not only the COVID-19 virus “threatens life”

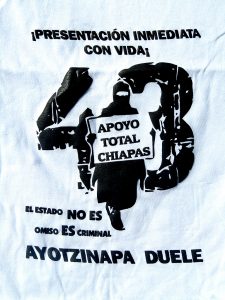

In February, the caravan “In Search of the 43” students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Normal School who disappeared in Iguala in 2014, in which their relatives participated, arrived at the Mactumactza Rural Normal School in Tuxtla Gutierrez. In response to a blockade, “more than two hundred state police officers with tanks and tear gas bombs stationed themselves at the entrance to the Normal School (…) without any protocol, began to drop the gas shells (…) with the toll of three wounded students, two mothers and a three-year-old granddaughter”, the Tlachinollan Centre for Human Rights reported. The Undersecretary for Human Rights, Alejandro Encinas, asked the state government “for the investigation and punishment of those responsible for giving the order to repress the caravan.” The State Attorney General’s Office reported that two police officers were detained and that an investigation is ongoing against “those who are responsible for the crimes of rioting, attacks against peace and the bodily and patrimonial integrity of the community and the state, and attacks on the means of communication, as well as injuries to four uniformed officers.”

Regarding defenders, in April, Frayba expressed concern about new death threats and surveillance acts against Father Marcelo Pérez Pérez, parish priest of Simojovel, “harassment that also endangers the security of his pastoral team and the general population.”

As regards forced displacement, from March to May, authorities from Aldama and Santa Martha (Chenalho), denounced acts of aggression between residents, which have their origin in a long-standing conflict due to the dispute over 60 hectares in the border area between both towns. The municipal president of Aldama and Frayba reported “attacks with firearms from paramilitary armed civilian groups in the communities of Santa Martha” against Aldama residents on an almost daily basis, with the result that “many families fled [again] towards the mountains.” At the same time, Santa Martha authorities have indicated that “their neighbours in Aldama were the ones who started the shooting.” Although a non-aggression pact was signed in June 2019, the attacks continued.

In May, gunshots were denounced in Chalchihuitan, allegedly perpetrated by an armed civilian group from Chenalho. In the context of the pandemic, these attacks put at risk about 1,236 displaced people, who are in extreme poverty. They obtained an injunction to protect their life and safety, but the authorities “have not effectively complied with its implementation”, Frayba claimed.

Land and territory: Defense initiatives continued

“Coca Cola Out”, one of the demands during the pilgrimage of Pueblo Creyente (People of Faith), San Cristóbal de Las Casas, January 2020 © SIPAZ

In March, members of the Regional Indigenous and Popular Council of Xpujil (CRIPX), the municipal seat of Calakmul, Campeche, and members of the human rights area of the San Cristobal diocese (which launched an initiative in a show of solidarity through which more than 12 thousand signatures were collected in 15 municipalities of Chiapas), demanded respect for the rights of the indigenous people affected by the Maya Train project, when international standards regarding consultation were not met, and by not presenting a study of environmental, economic, social and cultural impacts.

In March, the Popular Front in Defense of Soconusco “June 20th” (FPDS) reported that the Chiapas government called it to a working meeting in which representatives of the mining company El Puntal participated, “to warn them that the government will apply the “rule of law” for the titanium mining company to restart its works. In the presence of the Chiapas Prosecutor’s Office and the Agrarian Attorney’s Office, the businessman pointed out 12 members of the FPDS as the “leaders” of the organization and threatened to apply criminal complaints against them.” “Making use of the “rule of law” would be to review all the inconsistencies and irregularities that the project presents,” it claimed.

In March, the Trustee of the San Cristobal de Las Casas municipality asked the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) to revoke the concession granted to the Coca-Cola FEMSA company to exploit groundwater in the municipality. He asked “to give priority to the needs of the San Cristobal population over commercial and industrial use, since our municipality suffers from a shortage of water.” CONAGUA responded that “there are no elements” to “legally revoke the concession titles.” Groups defending the environment urged CONAGUA to “reconsider its position.” They stated that the “benefits derived from the generation of jobs (…), as well as the resources that it allocates for the financing of some civil organizations (…), are nullified and overcome by the damages and risks that the extraction of water produces.”

OAXACA: Struggles in defense of land and territory during the pandemic

In April, Governor Alejandro Murat published a decree outlining measures to confront the pandemic, one of them being the mandatory use of face masks in public. Those who fail to comply with this measure must pay a fine or be subject to arrest for up to 36 hours. Different organizations stated that this provision “invades federal powers and violates the human rights of indigenous peoples”, as they are excessive, especially for those who must go out day by day to earn a living. In May, Codigo DH won an injunction against state provisions, recognizing that federal criteria in no case consider the use of public force or the authorization of sanctioning or coercive measures.

As for defenders and journalists, in February, a reporter and a cameraman who were covering a protest about a land conflict in the Agrarian Court of the City of Oaxaca, were threatened with death if they did not delete their recording. Soon after, members of ten media outlets were physically and verbally assaulted. In the absence of police officers, the organization for freedom of expression Articulo 19 considered it “alarming that the safety of citizens and those who exercise freedom of expression is not guaranteed.” Oaxaca reporters protested the attacks, even more so because they join “an extensive list of grievances in which groups, unions, organizations and individuals believe that by attacking the representatives of the media they will only report what is in their interests.”

In May, a banner with death threats against the mayor and the members of the June 19th Committee of Victims for Justice and Truth (COVIC) appeared in the municipality of Nochixtlan. This organization was formed to demand justice following the police repression of June 19th, 2016, evicting members of the teaching profession and parents protesting against the educational reform bill of Enrique Peña Nieto, which left six people dead and 108 wounded. These threats are presumed to stem from advances in the investigation in recent weeks when Gabino Cue Monteagudo, a former governor of Oaxaca, as well as the state and federal security secretaries who were serving at the time, were summoned to appear.

As for land and territory, resources and coordination efforts continue to multiply. In February, indigenous people of San Pedro Quiatoni won an injunction against mining companies subsidiary of the US Gold Resource Corp for not having respected “the right to territory, nor the right to consultation and consent.”

Also in February, representatives of some 50 communities and 20 organizations formed the Oaxacan Assembly in Defense of Land and Territory, to “achieve consensus of struggle in the peaceful defense of Mother Earth, its cultures and its own forms of organization.” They denounced that “the Mexican government, as a faithful servant of transnational companies, has promoted the privatization of communal and ejido lands (…) in order to give legal security to companies” whose projects usually translate into “destruction of the social fabric, the immobilization of the protest, destruction and contamination of natural assets.”

Likewise, in March, the community of Santa María Zapotitlan won an injunction against the Zalamera mining company. The injunction considered that there is a collective interest since “territory is the key to the material, spiritual, social and cultural reproduction of an indigenous people.”

GUERRERO: Risk of invisibility of multiple problems

Guerrero is another of the states where it is feared that COVID 19 may have tragic impacts due to the sanitary, economic and social conditions prior to the pandemic. In April, municipal and community authorities highlighted the needs of the “indigenous and Afro brothers” not only in the health crisis but due to its consequences. They asked that “community decisions to establish control systems for the entry to and exit from many communities be respected.” They considered that “they are drastic but necessary measures of protection.” They asked for attention for the laborers who work in agricultural plantations in the North who were forced to return without “health care.” They also warned about the migrants in the United States, thousands from Guerrero in difficulty, some of whom returned and found their communities closed even to them.

Even in the emblematic case of Ayotzinapa, the Committee of Mothers and Fathers of the 43 students from the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa who disappeared in Iguala in 2014 has expressed its fear “that the media agenda focused on the health issue will make the disappeared invisible.” In March, three suspects involved in acts of torture against those prosecuted in the case were arrested. Furthermore, “the former director of the Criminal Investigation Agency (AIC), Tomas Zeron de Lucio, and the former head of the Federal Ministerial Police, Carlos Gomez Arrieta, are about to be arrested.” Accompanying organizations acknowledged these actions “because they confirm what families have always denounced: the manipulation of the investigation.”

On the question of defenders and journalists, in April, the Guerrero State Human Rights Commission (CDHEG) delegate, Eliseo Jesus Memije Martinez, was murdered along with his son in the municipality of Coyuca de Benitez.

Likewise, in April, Tlachinollan and the Red TDT (All Rights for All Network), denounced the risks run by the members of the Morelos y Pavon Regional Centre for Human Rights, who accompany the victims of forced displacement in the municipality of Leonardo Bravo. In April of this year, they, the displaced and the journalist Ezequiel Flores from Proceso magazine were threatened with death “by the group of armed civilians, the United Front of Community Police of the State of Guerrero (FUPCEG), through a publication on their Facebook page.” Articulo 19 indicated that in the case of Flores Contreras “verbal and physical aggressions against him (…) have been systematic on the part of agents of the State and alleged members of organized crime.” Articulo 19, has documented 280 attacks against the press in Guerrero, placing the entity as the fourth most dangerous state for the practice of journalism.

Meanwhile, displaced persons from the municipalities of Leonardo Bravo and Zitlala, denounced that “armed groups have taken control of the communities of Carrizal de Bravo and El Balsamar.” They demanded the presence of the National Guard, a request that appeared a year ago in the minute they signed with the Ministry of the Interior to “take control of security throughout the region, but the federal government has not followed through on this promise.”

In May, the opposition leader to the Media Luna mining company, Oscar Ontiveros Martinez, was executed by an armed group in the municipality of Cocula. Relatives denounced that “it was for political-labor reasons and in repression for his activism in the mining company (…), since he was a key worker in the work strike of November 2017.” They recalled that in 2018, three workers who participated in protests demanding union independence and respect for the rights of tenants were killed.

As regards advances, in April, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) declared the modifications of Law 701 of Recognitions, Rights and Culture of Indigenous Peoples and Communities of the State of Guerrero of 2018 unconstitutional “since there was no prior, free, informed, good faith and culturally appropriate consultation.” Tlachinollan welcomed that the ruling left “clearly established that it is not the state authorities that can unilaterally decide the course of the peoples’ lives.”