Urgent Action – Case of Ayotzinapa, Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico

17/10/2014IN FOCUS: Children and adolescents in Mexico – an uncertain future

24/11/2014Three violent events in recent months have generated disapproval of Mexico. In July, José Luis Alberto Tlehuatle Tamayo, 13, was wounded by the impact of a rubber bullet fired by federal police in the state of Puebla, whilst they attempted to break up a demonstration. Two months earlier, the local Congress had approved the “Protection of Human Rights and the Regulation of Fair Use of Police Force act” better known as the “Bullet Law”. On 22nd July, 22 civilians were killed by soldiers in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico: Seven of them died during the shootings; the other 15 were executed after surrendering. Finally, on 26th and 27th September in Iguala, Guerrero, municipal and members of an unidentified police force fired on passers-by and students of the rural Teacher Training School Raúl Isidro Burgos in Ayotzinapa, normalistas as the student teachers are known. The result was six dead (3 of them from Ayotzinapa), 25 wounded and the forced disappearance of 43 normalistas. Their whereabouts are still unknown, although nineteen clandestine mass graves containing dozens of bodies have been found, they were not those of the normalistas. In November, the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) declared that, according to confessions by gang members, the 43 missing normalistas were executed and then their bodies burned. Relatives of the 43 missing will not accept this version until forensic evidence supports this statement.

On 12th October, representatives of the European Union (EU) condemned the violence in Tlatlaya and Ayotzinapa. On 5th November, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico said Tlatlaya is just a case of a larger set of crimes committed by soldiers and police who have not given rise to a reaction from the State. On 30th October, the executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), Emilio Álvarez Icaza said that “it is not only unfortunate what happened in Ayotzinapa, Tlatlaya and Puebla; what it is more worrying is that these events are similar to events that happened in the past”. By the end of October the White House in the United States also claimed to be “concerned about the reports” related to the disappearance of the normalistas.

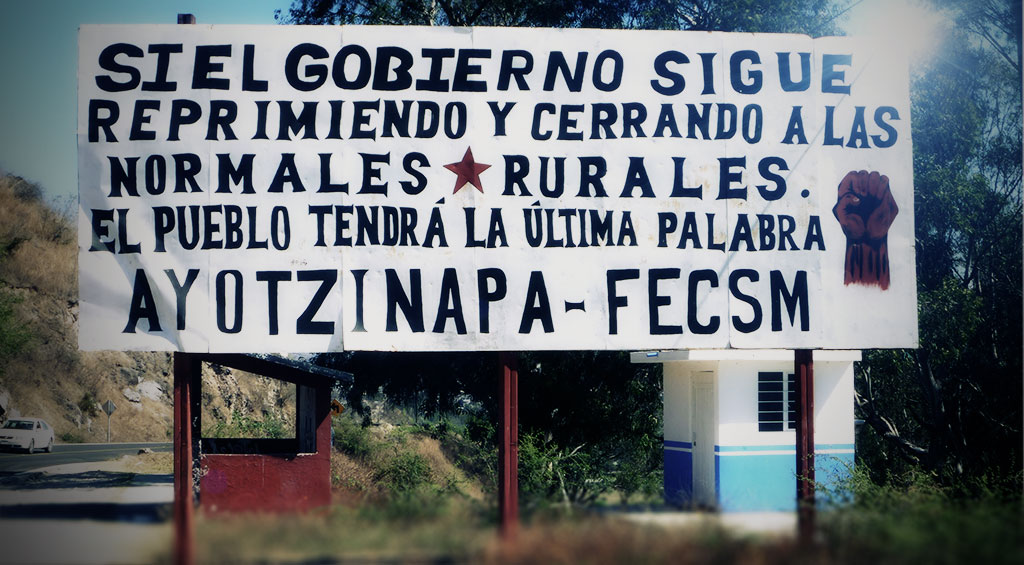

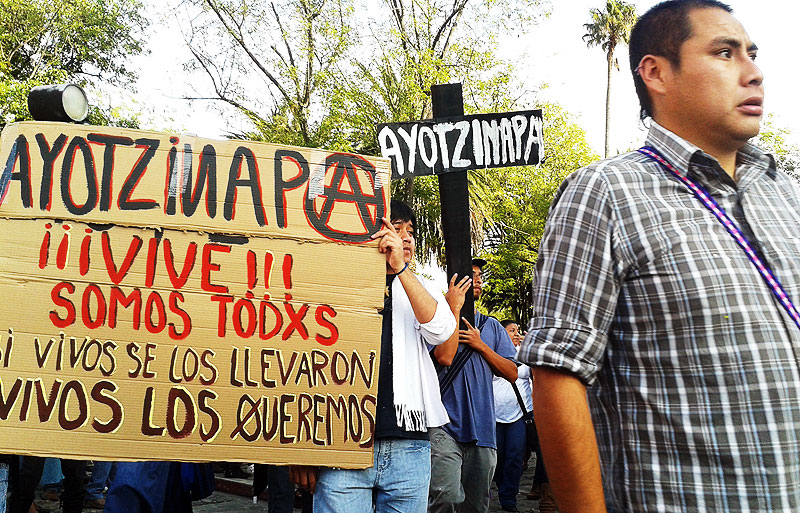

At the same time, and for several weeks, the international press which had previously welcomed Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration, became daily more critical of his government and the situation in the country. “Ayotzinapa” has generated massive demonstrations in Mexico and abroad, most of them taking place peacefully, however some took a violent turn in the areas of Guerrero, Michoacán, Chiapas and Mexico City. On 8th October, millions of people from at least 25 Mexican States and various cities in America and Europe took part in demonstrations demanding the return with life of the 43 missing normalistas. In the State of Chiapas alone, more than 60,000 people joined the demonstrations, including 20,000 bases of support from the Zapatista Army for National Liberation (EZLN). On 22nd October, the day “A light for Ayotzinapa” took place in dozens of cities in Mexico and abroad. In November, normalistas and relatives of the disappeared launched a “National Brigade” which will travel around the country; it includes three routes, one north, one south, and a local brigade which will traverse several municipalities within Guerrero. The aim of the initiative is to provide direct information and “seek proposals for a program of struggle and action to transform the reasons that led to the events on 26 and 27 September.”

Ayotzinapa reveals the crisis of human rights in the country

© SIPAZ

The human rights crisis in Mexico, which was revealed by Ayotzinapa, was flagged up by civil organizations long before. In September, Amnesty International published a report entitled “Out of Control: Torture and other ill-treatment in Mexico” which stated that “[i]n 2013, the number of complaints (1,505) increased by 600% since 2003”. In August, Urgent Action for Human Rights Defenders published the report “Defending human rights in Mexico: a fight against impunity”. It states that in the period since Enrique Peña Nieto took office, 669 arbitrary political arrests had been recorded, 25 extra-judicial killings and 29 enforced disappearances. It states that not including arbitrary arrests in Mexico City, the most dangerous states for the work of human rights defenders are Oaxaca, Chiapas and Guerrero.

After the Ayotzinapa case in October, Mexican NGOs attended the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, USA, to report cases of impunity and human rights violations in the present. The first hearing had been requested by the Mexican government to present the National Human Rights Program. At the gates of the venue where hearings were held, dozens of demonstrators gathered with photographs of the missing students. Lía Limón García, Under-Secretary for Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Ministry of Interior Affairs acknowledged that Mexico is going through a testing time for progress on human rights and stated that “the Mexican government will not rest until we find the students”.

The NGOs for their part complained that “the humanitarian crisis facing the country based on the testimony and reports of persons disappeared, killed, displaced, tortured, injured has been ignored, rewritten, hidden, dissimulated, and reduced to statistics manipulated by the government”. They stated that “the government’s efforts are concentrated on showing the “Mexican moment” of supposed progress and welfare.” They declared that the State “is responsible for the perpetration and perpetuation of serious, widespread and systematic human rights violations.” The “connection between impunity for crimes during (…) [the] so-called Dirty War and what is happening today” was also stressed.

Presidential Report: triumphalism overtaken by more recent violent events

© SIPAZ

The facts reported above shattered the image of Mexico which the government of Peña Nieto had been promoting abroad and which he also wanted to emphasize in his second presidential report in September. Among the achievements, he stressed the approval of eleven structural reforms. Other achievements he could boast about were the arrest of drug trafficker “Chapo” Guzmán and having regained some control in Michoacán slowing the advance of organized crime. In addition and on the very day of the report, finally implementing a campaign proposal, the National Gendarmerie began operating. NGOs expressed concern about the creation of a police force with military training which is not focused on protecting citizens’ rights, a concern that cannot be taken lightly after events such as Tlatlaya.

By 1 September, the perception of Peña’s administration was highly positive in multilateral economic organizations and international media. Surveys at that time, however, indicated that 6 out of 10 Mexicans did not approve of his economic management and that the energy reform had a 60% disapproval rating. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, of the countries evaluated, Mexico was the only one where the population living in poverty increased. There have also been questions about the reforms, which did not include a social policy that would go beyond a welfare logic.

In contrast to the presidential report, NGOs drew an extremely worrying picture. Services and Consulting for Peace (Serapaz) warned that in the two years of the administration at least 23,640 murders and 22,322 disappearances have been reported. Article 19 reported that during Peña Nieto’s administration seven journalists have been killed and that in 2013 there were 330 attacks on the press, and over 150 journalists were attacked in the first half of 2014. The Mexican Institute for Human Rights and Democracy said that in the report ” the only achievements presented are a series of laws and programs that do not translate into concrete actions or results” and “it does not address serious problems that continue to occur in the country” such as punishment or torture.

GUERRERO: in the eye of the hurricane

The case of Ayotzinapa sparked strong criticism of the state government. Some of the relatives of missing students even reported that the Guerrero state government had offered 100,000 pesos per disappeared person, in return for not talking and stopping the search for them. On October 23, after much pressure, the governor of Guerrero, Angel Aguirre Rivero, resigned. His administration had actually begun with the murder of two student teachers from Ayotzinapa in 2011 as part of an evacuation of a blockade where federal and ministerial police were involved.

Ayotzinapa laid bare profound institutional weakness especially at the state and municipal level where corruption and collusion between police, local politicians and organized crime were identified. On November 4 the former mayor of Iguala, Jose Luis Abarca and his wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda, were arrested in Mexico City: they are the alleged masterminds in the case. These arrests brought the number of people detained to 74. However, there has still been no significant progress in the location of missing persons.

More broadly, the situation of human rights defenders in the state remains one of extreme vulnerability. On October 9, Saira Rodríguez Salgado, daughter of Nestora Salgado García, commander of the community police in Olinalá, currently imprisoned in the federal maximum security prison in Tepic, Nayarit, was threatened with death. On October 27, she reported that for this reason she intended to take up residence in the United States. Her complaint was not followed up, she said. In August her mother completed a year in prison. The National Network of Human Rights Defenders in Mexico has denounced “the political nature of the prosecution and the illegal use of federal prisons with the complicity of the Federal Government, from which no human rights defender in Guerrero is exempt.”

In October, María de la Cruz Dorantes Zamora, a member of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to La Parota (Cecop), was also detained, charged with the crime of aggravated robbery, one of the indictments issued to Cecop spokesman, Marco Antonio Muñoz Suástegui, detained since last June and currently being held at the federal prison in Tepic.

In November, the acting governor of Guerrero, Rogelio Ortega Martínez, said he has sought rapprochement with the relatives of the Ayotzinapa student teachers, but regretted that “radical” groups like the Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center and the Coordinating Organization of Education Workers in Guerrero (CETEG), hindered this dialogue. The director of Tlachinollan lamented the “media lynching” against Tlachinollan which jeopardizes the work of human rights defenders who make up the center. He said that they have been respectful and that the parents of the missing “are the ones who decide.” In addition, an intelligence report from the Mexican government was leaked, which accuses José Manuel Olivares Hernández, Technical Secretary of the Guerrero Human Rights Network, of being linked to a guerrilla group, another allegation refuted by human rights organizations and which makes the work of defenders in the state more difficult.

OAXACA: same pattern of killings, arrests and harassment for defenders

In Oaxaca too, human rights defenders are subject to multiple hazards. In August, Silvia Pérez Yescas, a member of Conservation, Research and Use of Natural Resources – CIARENA, was informed that in San José Río Manzo there was a price on her head. In recent years, she has received more than ten threats against her, which is why she obtained protection orders. In September, civil organizations and federal legislators urged the PGR to avoid imprisoning Bettina Cruz Velázquez, a member of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defense of Land and Territory (APIIDTT), released facing prosecution for the offense of illegal deprivation of liberty and crimes against consumption and national wealth, for peaceful participation in a demonstration against high electricity tariffs in 2012. Also in September, Jaime López Hernández, member of Indian Organizations for Human Rights in Oaxaca (OIDHO ) was murdered in San Juan Ozolotepec. Services for Alternative Education (EDUCA) indicated that “[i] t is worrying to see increasing political violence in Oaxaca and impunity for attacks on leaders and human rights defenders”. In October, the home of Silvia Hernández Salinas, member of Oaxacan Voices Constructing Autonomy and Freedom (VOCAL) was raided and her computer and two hard drives were removed.

On October 2 there was a march in Oaxaca City to commemorate the Tlatelolco massacre (1968, Mexico City). 75 people were arrested, mostly minors and members of OIDHO and of Section XXII of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE). They were arrested on suspicion of acts of vandalism allegedly committed by a group of ‘anarchists‘ in commercial establishments and government offices. They were later released.

In September and October, physical and verbal attacks on members of the Migrant Hostel “Hermanos en el Camino” [brothers on the way] were reported. Since the implementation of the Southern Frontier Plan, 57 migrant people have been victims of serious crimes such as robbery, extortion, rape and injuries, according to documentation at the Hostel which claims that attacks against this section of the population have increased by 90%.

In November, members of the Popular Assembly of the Juchiteco People (APPJ) and APIIDTT reported harassment and threats within and outside the preliminary consultation on the installation of a wind farm in Juchitán. This is a project that would be provided by Energía Eólica del Sur [Wind Energy of the South] (formerly Mareña Renewables) and which would involve 132 wind turbines. Código DH [Human Rights Code] reported that these attacks “pervert the first phase of this consultation process, as the participation of all concerned should be guaranteed”. Several social organizations have questioned this consultation, regarding it as a “mockery” and a “circus“, since the process started after there were already almost 13 wind farms and over 800 towers in Juchiteco territory.

Chiapas: Impunity, Land and territory in the heart of social struggles

In October, about 10,000 Catholics made a pilgrimage in the municipal center of Simojovel to demand the closure of centers of prostitution, an end to the sale of alcohol, drugs and weapons in this municipality, and to report threats. The Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas Human Rights Center (CDHFBC) noted “the failure and inefficiency of the state government to investigate the various death threats received by members of the Parish Council and Father Marcelo Pérez Pérez, (…) the failure to propose effective mechanisms to meet the various other demands which have been raised.” Later, members of the Pueblo Creyente of Simojovel denounced new and repeated threats of kidnapping and death by the authorities and groups which deal and traffic in the municipal center.

Another source of mobilization and acts of harassment has been opposition to the construction of the mega-highway between San Cristóbal de Las Casas and Palenque (see article). In August, an assembly was held in the ejido San Jerónimo Bachajón, Chilón municipality, in which the ejidatarios expressed their opposition to the project. They said that they had not been consulted about the construction and they will not sell their land. They denounced that their ejidal commissioner has been harassed to sign the authorization. In September, ejidatarios from Candelaria, in the municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, also made public their opposition to the mega-highway. They denounced pressure and threats from government officials. In October and November days of mobilization were held where hundreds of people participated.

The theme of the defense of land and territory remains the driving force behind struggles in and outside the state. In September, the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) and the EZLN issued a pronouncement for the freedom of Mario Luna, spokesman for the Yaqui tribe in the state of Sonora, who was arrested “falsely accusing him of crimes that they themselves planted. With this action they intend to imprison the very struggle of the Yaqui Tribe to defend its waters, which (…) were recognized as theirs in 1940 by Lázaro Cárdenas.”

They denounced that “It is a joke to say that the Independence Aqueduct is so that the poor have water and progress, as those above say.” They stated that the mega-projects of development are a danger to the lives of indigenous peoples as “they are trying to kill us with wind turbines, with highways, with mines, with dams, with airports, and with narcotrafficking.” In October, the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center denounced acts of harassment against the ejidatarios of Tila during and after the march, in which 1,500 ejidatarios took part, in the centre of the municipality commemorating the creation of the ejido 80 years ago. In November, in the town of Chicomuselo, various activities were carried out to protest against mining and to organize in defense of life. At the end of the march, they declared Chicomuselo to be a “municipality free of mining.” In this context, the Third Forum for the Defense and care of Mother Earth, in which about 3,500 people participated, was also carried out.

A further reason for alert: Chiapas has been placed among the top ten states with the highest number of femicides. In 2010, 22 were recorded; in 2012, 97; in 2013, 83 were registered and from January to date 41 cases have been documented, according to the San Cristóbal Women’s Group. The “popular campaign against violence towards women and femicide in Chiapas” reported that “(t)he government of Chiapas does not comply with the law in the convictions of cases of femicide, the punitive measures applied to femicides being excessively light.”

Also on the subject of impunity, the United States Supreme Court rejected the appeal filed by 10 people who charged the former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León (1994-2000) for the Acteal massacre (1997). In November, three people indicted for the same massacre were released. Currently, only two people remain imprisoned for these acts. In October, an event was held in Masojá Shucjá, Tila, to remember the victims executed, disappeared and displaced in this region between 1995 and 1999. The CDHFBC said: “in the lower area of Tila, [the paramilitary group] Paz y Justicia committed at least 37 forced disappearances, 85 executions and more than 4,500 people were obliged to become forcibly displaced to save their lives, also suffering harassment, intimidation, destruction of property, torture, sexual torture, and arbitrary detentions among other human rights violations. (…) Tragically, these serious human rights violations have remained unpunished”. In November, a pilgrimage was undertaken to remember the victims of the Viejo Velasco massacre (4 dead, 4 missing), in the municipality of Ocosingo and to demand justice against impunity. Meanwhile, seven organizations for the defense and promotion of human rights in Chiapas began a campaign called “Faces of Dispossession,” which seeks to “make visible the ways in which indigenous peoples are violently evicted from their territories.”