Chiapas: SIPAZ regrets the murder of Father Marcelo Pérez

21/10/2024

FOCUS: Violence against Children and Adolescents in Mexico. The Case of Chiapas

21/12/2024

t he elections in the United States revive the saying: “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States.” The elected candidate, Donald Trump, has declared that he will impose a 25% tariff war against Mexico if Claudia Sheinbaum’s government fails to contain the flow of migrants and fentanyl trafficking across the 3,000 kilometers of border that both countries share. Trump arrives with stronger than in his first term: the Republicans have achieved control of Congress, and the conservatives dominate the Supreme Court. In addition, he has an additional element of pressure: the review of the Treaty between Mexico, the United States and Canada (USMCA), scheduled for 2026, with the United States being Mexico’s main trading partner.

Migrants carry a cross at the front of a caravan that aims to reach the border between Mexico and the United States, leaving from Tapachula, Chiapas state, on March 25, 2024 © Isaac Guzmán/AFP via Getty Images

During Trump’s first term and with Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador in the presidency of Mexico, Trump announced a general tariff of 5% in response to what he considered inaction by the Mexican authorities to stop the migrant caravans. Faced with this threat, the Lopez Obrador administration, initially more permissive, reinforced the northern and southern borders with a strong military deployment, a strategy that has been maintained to date with disastrous results in terms of human rights. Currently, Mexico already operates as a safe third country, accumulating thousands of migrants awaiting asylum in the United States on its northern and southern borders.

Claudia Sheinbaum has insisted that transnational migration must be addressed through social solutions in the countries of origin, an initiative that clearly does not coincide with the Trump agenda.

For his second term, Trump has promised to carry out the largest deportation of migrants in history, including undocumented immigrants, their spouses, children and other relatives. Remittances sent by Mexicans in the United States are one of the pillars of the Mexican economy, ranking, according to official figures, between the second and third source of income after tourism and oil sales. If only a part of the promised “mass deportation” were to materialize, there would be sufficient reason for concern in Mexico. Currently, it is estimated that five million Mexicans reside in the United States in an irregular situation.

Another point of tension will be the policy of combating drug trafficking. Even as a candidate, Trump said that the Mexican cartels have such power that “they could remove the president in two minutes. They are the ones who run Mexico.” Among his plans, he contemplates classifying the Mexican cartels as terrorist organizations, which would give him the power to intervene beyond his territory. Trump has promised to bomb fentanyl laboratories and block ports that transport its chemical precursors. Although Claudia Sheinbaum has not commented on these initiatives, they could be interpreted as direct interference in Mexican sovereignty.

In the face of threats, Sheinbaum has sent messages of reassurance to preserve stability in bilateral relations. However, the Mexican peso has fallen to its lowest level in more than two years, reflecting the uncertainty. Added to this are internal factors that have accentuated this trend, in line with pessimistic predictions about the performance of the Mexican economy.

Claudia Sheinbaum, between Continuity and Change

Claudia Sheinbaum, surrounded by women from different indigenous communities, during the ceremony to hand over the baton of command © Nayeli Cruz / El País

On October 1st, Claudia Sheinbaum was sworn in as the new president. She won the election with 36 million votes, beating her main competitor, Xochitl Galvez, by 30 percentage points. Sheinbaum begins her mandate with a qualified majority in Congress, the support of allies in 24 governorships, a weakened opposition, and a recently approved judicial reform that will allow the ruling bloc to reconfigure the Judiciary. The 100 points of her government plan propose to continue the themes of the outgoing government, such as austerity, the fight against corruption, and the expansion of social programs, in addition to establishing new priorities such as the promotion of women, education and science, the protection of the environment, and the fight against machismo and racism.

The period analyzed in this report has been marked by a wave of reforms, a trend that began at the end of AMLO’s term, who sought to cement his legacy, and accelerated with the arrival of Sheinbaum to power thanks to her majority in Congress.

Among the most relevant reforms, still under the presidency of Lopez Obrador, the approval in September of the initiative that incorporated the National Guard (GN) into the National Defense Secretariat (SEDENA) both administratively and operationally stands out. The Miguel Agustin Pro Juarez Human Rights Center (Centro Prodh) described this measure as “a point of no return towards militarization.”

Concern about the implications of this reform was illustrated in October, when six migrants died and ten more were injured after a chase in the municipality of Villa Comaltitlan, Chiapas, at the hands of members of the Mexican Army. According to SEDENA, the military detected a vehicle traveling at high speed that tried to evade them. Faced with alleged shots, two soldiers fired. SEDENA reported that the members involved were removed from their duties and “as this was an incident in which civilians were affected, the Attorney General’s Office was informed so that it can carry out the necessary legal proceedings.” The Southern Border Monitoring Collective demanded justice for the victims, pointing out that this incident is a “direct consequence of ordering military deployment to contain migratory flows under a logic of persecution and not protection of people on the move.”

In September, the reform on indigenous and African-American peoples was approved. Among the most notable advances, they are recognized as subjects of public law and not only as objects of public interest, which will allow them to receive and manage budgetary resources directly. In addition, the reform establishes the obligation to provide them with adequate jurisdictional assistance through interpreters, translators, defenders and specialized experts. However, opposition deputies described the reform as insufficient. This perception was shared by experts and organizations, who considered it “superficial” as it was limited only to the Article 2 of the Constitution, and pointed out that “it will not have any practical effect.” Criticism focused especially on the lack of progress regarding the issue of land and territory, considered fundamental for the exercise of self-determination.

Also in September, the judicial reform was approved, perhaps the most controversial and questioned at international level. In November, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) expressed its concern about this reform, warning that it could put judicial independence at risk. For its part, the Mexican government argues that citizens must have the right to elect judges, and defends the constitutionality of the reform, approved by a large majority in Congress. However, members of the judicial branch denounced the Executive’s interference in the Justice system, alleging that it violates the labor rights of judicial officials and the independence of the administration of justice. Before the IACHR, the Mexican government has argued that “this reform was necessary to regain public confidence in the courts and in the justice system in general, since in Mexico judges […] have released common and dangerous criminals, drug traffickers, have issued sentences without a gender perspective, have legalized the dispossession of indigenous peoples’ lands, and the nepotism of the judicial powers is widely documented.”

In October, already under Claudia Sheinbaum’s mandate, more than one hundred civil organizations asked to reject a reform that sought to eliminate transparency bodies. They argued that this change would open the door for “the delivery of information and transparency to be subordinated to the Executive, in a context in which denials of information and reservations to it have increased.” They asked to “generate an open process that allows improving the current institutional framework that ensures society’s right to know.” However, this reform was approved in November without further debate.

Human Rights: Continuing Concerns

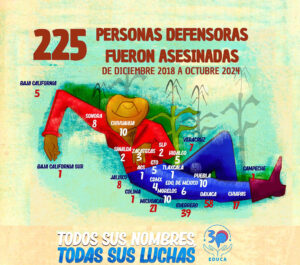

In October, EDUCA presented a study on Serious Attacks on Human Rights Defenders in Mexico. Between December 2018 and October 2024, 252 attacks on the lives of human rights defenders were recorded: 225 murders and 27 disappearances. Of these cases, 42 were classified as extrajudicial executions. The most dangerous struggles were for the defense of territory and civil rights (80%). The South-Southeast is the most dangerous region, accounting for 51% of the cases. 62% of the murdered defenders belonged to an indigenous people and 57% were peasants. In addition, 20% of the victims were women or people of sexual diversity. “The data show that there is a failed security strategy at the national level. We note the weakening of protection agencies and autonomous human rights organizations. What was reinforced in this government was the culture of impunity; the militarization of public security; access to justice became the exception and not the rule,” the study highlighted.

In November, the Senate approved the reelection of Rosario Piedra Ibarra to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), despite being the worst evaluated candidate among fifteen. Already in September, a hundred civil organizations had pointed out that the administration of Rosario Piedra Ibarra, which started in 2019, “has faced serious criticism for not fully, objectively and comprehensively addressing the crisis of serious human rights violations that the country is going through.” “The deliberate surrenders and omissions reflect a partiality in her actions in accordance with the administration [of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador] that left aside serious human rights violations.” There is concern that this trend will continue during a new term, now under the presidency of Claudia Sheinbaum.

CHIAPAS: Advance of Criminal Violence Continues to Be Cause for Concern

In September, thousands of people called by the Ecclesiastical Province of Chiapas went on a pilgrimage to Tuxtla Gutierrez to denounce the lack of peace and security in the state. They pointed out that “the violence generated by organized crime groups, at war for control of the territory, has been advancing considerably in several municipalities.” They added that “the cause of this violence is due to the interests that drive the construction of an infrastructure of plundering of natural resources (…); this developmental economy requires lands and territories free of settlers (…) The exponential increase in insecurity has increased murders, disappearances and forced displacement.” They demanded that the authorities “consolidate the rule of law, respect for human and collective rights, as well as the establishment of social order without putting civil society at risk; the dismantling and immediate disarmament of criminal groups,” among other measures.

The main hotspots continue to be the Sierra and Border area, which has become “a battlefield over the dispute over territory between criminal groups that force men to go to the front, to take care of the pens, to close roads,” declared bishops from Chiapas and Guatemala in August.

Another hotspot is Pantelho. In September, the outgoing Congress of Chiapas appointed a municipal council, which includes the brother of Daily de los Santos Herrera, who was sentenced to 25 years in prison for the intellectual authorship of the murder of indigenous prosecutor Gregorio Perez Gomez in 2021. The inhabitants of the municipality affirm that this new council is made up of people close to the leaders of “Los Herrera” cacique group, linked to murders and organized crime. For their part, sympathizers of the self-defense group “El Machete” warned that they will not recognize the council appointed by Congress. Since 2021, after an armed uprising against “Los Herrera”, this cacique group and communities organized in “El Machete” have been fighting with arms for power in Pantelho, leaving dozens dead and wounded, as well as displaced families.

Another source of conflict arose in October, when the Zapatista village “6 de Octubre”, in the municipality of Ocosingo, was attacked by armed people from the community of Palestina. They settled on recovered lands threatening residents with eviction. Since June, “the threats have escalated to include the presence of people from Palestina with high-powered weapons, threats of rape of women, burning of houses and theft of belongings, crops and animals,” said Sub-commander Insurgente Moises. For this reason, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) initially suspended all information and communication about the “Encounters of Resistance and Rebellion 2024-2025”. However, the first dates were later confirmed for late December and early January.

Attacks on Journalists and Defenders: Upward Trend

Another worrying trend has been the increase in attacks on journalists and human rights defenders. In August, armed men shot journalist Ariel Grajales Rodas in Villaflores. This journalist reported on both official information and acts of violence, including the charging of protection money for all commercial activity in the Frailesca region.

In September, the Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Human Rights Center (Frayba) denounced the increase in violence against members of its team. It reported that since January it has “recorded four attacks, assaults and delegitimization of our work,” and that, from July to date, its members have received death threats and the home of one of them was raided. Added to this “is extortion, intimidation, surveillance and verbal attacks, and several of them come from players linked to the municipal, state and federal governments,” it denounced. All this despite the fact that the organization has Precautionary Measures granted by the IACHR. It regretted that the government “cannot stop the whirlwind of violence, on the contrary, the risks are increasing and with them to those who defend human rights.”

Likewise, in September, journalist Dalia Villatoro reported threats against her. She explained that “alleged members of organized crime launched a threat against me, hanging a poster outside my home in which they linked me to publications made through the Facebook pages Notifraylesca and Villaflores.”

As for the most notorious case, on October 20th, Father Marcelo Perez Perez was murdered in San Cristobal de Las Casas. Ordained in 2002, he had become a reference as a defender of human rights and the defense of Mother Earth, in addition to being a mediator in various social conflicts. Since 2015, he had received protective measures from the IACHR due to the constant threats he faced for his work. Several organizations, networks, and collectives have spoken out about the murder. President Claudia Sheinbaum lamented the murder and assured that an investigation is already underway to clarify the crime. On October 22nd, Edgar “N” was arrested and charged with criminal proceedings for his probable responsibility as the material author of the homicide. The speed with which the arrest took place makes many analysts doubt that he is truly guilty and, in any case, they urge that the investigation find the intellectual authors of the crime.

OAXACA: Still High Risks for Human Rights Defenders

In the EDUCA study on Serious Attacks on Human Rights Defenders in Mexico, Oaxaca tops the list with 58 human rights defenders murdered between December 2018 and October 2024. Attacks continue to be frequent.

In August, the “Participatory Diagnosis: Towards a Public Policy for the Comprehensive Protection of Women Defenders and Journalists in Oaxaca” was presented. The diagnosis documents that, between 2018 and 2022, 14 women defenders were murdered in Oaxaca and that, from 2016 to 2019, 1,063 attacks against this sector were recorded. Women defenders and journalists face the risk of being silenced through “threats of violence, including sexual violence; they also run the risk of being victims of femicide, rape, acid attacks, arbitrary arrests, imprisonment and forced disappearance.” One of the most worrying patterns is criminalization.

In September, the Bartolomé Carrasco Briseño Human Rights Center C.A. (BARCADH) reported a cyber-attack on its social networks. It stated that “our organization supports serious cases of human rights violations against victims and groups that come for our support; that is why we are alarmed and concerned about this situation.”

Also in September, human rights defender Daniel Bautista Vasquez was found dead in Villa de Etla. He was a beneficiary of precautionary measures by the IACHR. In March 2020, his brother Angel was tortured by members of the municipal police of Tlaxiaco. After these events, Daniel and his family reported police abuse, which led to multiple threats and harassment towards them.

On October 4th, Mixe lawyer Sandra Dominguez Martinez and her husband disappeared in the Sierra Mixe of Oaxaca. Sandra was dedicated to defending human rights and, since 2020, had denounced cyberbullying, gender violence and the participation of officials in the WhatsApp group “Sierra XXX”, where pornographic photographs of indigenous women were shared. Since November 6th, Sandra’s relatives set up a sit-in in front of the Government Palace in Oaxaca, to demand her appearance. They have reported that both the relatives and their lawyers have been victims of surveillance and intimidation.

On November 5th, sisters Adriana and Virginia Ortiz Garcia, indigenous Triqui defenders, were murdered in Oaxaca de Juarez. Both were activists of the Triqui Unification and Struggle Movement (MULT) and had worked intensively in the defense of human rights and in the search for their cousins, who disappeared in 2007.

In more general terms, in October, the Ombudsman for Human Rights of the People of Oaxaca presented a report on internal forced displacement in which it recognized that the victims of this phenomenon are “invisible and without recognition of their rights.” The report shows that the causes of forced displacement in the state are multiple: the imposition and application of community sanctions, not sharing the same religious belief, conflicts over land and territories that are mainly due to the lack of definition of land rights, conflicts in appointments in elections, among other causes. “Recognition of the human rights of displaced people has been slow. For many years, there has been no will on the part of some institutions and public policies in the past were not appropriate. In addition, the lack of legislation to address this social phenomenon has placed victims in a state of vulnerability,” the Ombudsman’s Office said.

In November, 91 women had already been murdered in Oaxaca in 2024. The Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity condemned the escalation of feminicidal violence recorded in recent months due to the inaction of the Government of Oaxaca. “We demand that Salomon Jara guarantee the safety of women and girls in the face of the violence that permeates Oaxaca, which is reflected in 677 disappearances and 204 feminicides during his government,” it declared. According to data from Mexico Evalua, in Oaxaca impunity for the crime of femicide reaches 100%, while in cases of disappearance it is 99.6%.

GUERRERO: “Unstoppable Violence”

In November, the Tlachinollan Human Rights Center warned about the levels of violence that have been reached in Guerrero: “The expansion of crime reaches the point where it comes up against another group that has territorial control. It is the criminal groups themselves that set limits and not the state institutions. The firepower of criminals leads them to challenge the security forces. Their weapons are sophisticated and they are better equipped. They have multiple contacts to supply weapons from the United States. They have properties in strategic places (…). They have resorted to recruiting young people to expand their domain and have human reserves for their armed incursions. The objective is to displace the group that runs the turf. The young people are cannon fodder that is discarded without legal consequences or forceful actions to contain this unstoppable violence. Criminal enterprises are very profitable businesses because they have been able to enter into various commercial lines where they launder their money with well-established companies. This is only feasible in states where corruption prevails, where the law is not applied and justice is a commodity that generates large dividends. (…) The weakening of public institutions has led to the overflow of organized crime that has established itself in tourist centers, in the main cities, in municipal capitals and in rural communities. It appears as the monster with a thousand heads, as the de facto power that has been installed within the public administration.”

In September, at least 10,000 people, including students, student teachers, university students, academics, organizations, groups, unions and individuals, marched in Mexico City ten years after the disappearance in Iguala of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Normal Rural School. President AMLO had promised to resolve this case during his six-year term, but he failed to do so. “He betrayed the trust that we as parents placed in him and turned his back on the Ayotzinapa Case in order to protect the army,” said Hilda Legideño, mother of Jorge Antonio Tizapa Legideño who disappeared that night. Mario Gonzalez, father of the missing student teacher Cesar Manuel Gonzalez Hernandez, said that “anyone who covers up or hinders investigations is also an accomplice to forced disappearance.” He warned: “If the incoming government is thinking of doing this, we will continue to fight.”

In this same spirit of struggle, in October, the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (CRAC-PC) celebrated its 29th anniversary. It stated that “the CRAC-PC is here, standing, weathering the storms caused by the actions of local bosses and governments. Our justice system has proven to be effective and successful in the face of the humanitarian disaster that criminal groups have caused.” It spoke about the recently approved indigenous reform, questioning that “political representation and the ownership of territories and natural resources were completely left out of the recently approved reform. Without territory, where will we exercise self-determination, autonomy and justice? The backbone of indigenous law: security and justice, government and ownership of our territories and natural resources were not incorporated into the reform. The historical debt to our peoples continues.” “Social programs are of little use if our rights are not recognized. If they are not accompanied by constitutional recognition, they will ultimately become a patronage and welfare mechanism that will keep us mired in backwardness and marginalization,” it concluded. It announced that it will continue “exercising security, justice and re-education with or without a law (…). We are not bound to a written law, on the contrary, we are governed by words, by dreams, by signs, by another way of being and existing in the world.”