2016

17/03/2017

FOCUS: National Indigenous Congress Proposal – “Echoes of Hope…”

14/04/2017The night of November 8, 2016 shocked the whole world when, in spite of the forecasts and rejection by broad sectors both inside and outside the United States, Republican candidate Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election.

These results present a multiple risk scenario on an international level in light of his “America first” approach, which includes, among other worrisome elements, a certain disdain towards the United Nations (UN) and the rejection of scientific studies that have led to an attempt at international responses to global warming.

As an immediate neighbor of the U.S. giant and with an economy that is very dependent on its relationship with it, Mexico is in a situation of extreme vulnerability. His campaign promises included driving out undocumented immigrants (11 million of Mexican origin), withholding some of the remittances sent by immigrants to their families, expanding the border wall at the expense of the Mexican people, renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, approved in 1994), and sanctioning US companies that move their production plants to Mexico through tariffs and other protectionist measures.

Nevertheless, Donald Trump has, and will have, difficulties in fulfilling his promises, because to do so, he would need to change laws and have access to funds that depend on the Congress. In other counterweights, it is worth mentioning that although he won by means of the indirect vote of the Electoral College, he lost the popular vote and ample sectors have mobilized against him. It remains to be seen how much of his projects he will actually be able to impose and what consequences will follow…

National: internal challenges

On January 1, the price of gasoline and diesel increased by 20% in Mexico. This increase goes hand-in-hand with an increase in other goods and services, significantly affecting the standard of living of the population. President Enrique Peña Nieto (EPN) – whose popularity rating barely reaches 25% according to polls – has defended this increase claiming “it was a necessary measure for the stability of the country’s economy.” The “gasolinazo” sparked protests, road blockades and the takeover of gas stations, among other actions in at least 25 states, leaving, to date, a toll of three dead and 600 arrested. The demonstrations also included a series of lootings of 400 commercial establishments. However, in several places it has been verified that these acts were provoked or coordinated with the authorities.

On another front, December marked a decade since the beginning of the war against crime launched by ex-President Felipe Calderon Hinojosa (2006-2012) with an alarming toll: 186,000 dead, more than 28,000 disappeared (which increases to a rate of 11 disappearances per day according to the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center (Centro Pro DH)), tens of thousands of displaced persons, a balance comparable to that of Central American armed conflicts in the 1980s. Over one billion pesos have been spent without reducing insecurity, harassment of civilians, and has implied a significant increase in human rights violations. Furthermore, domestic drug use has increased and, although some capos (cartel leaders) have been arrested, nine organized crime cartels and 37 criminal cells continue to operate. Civil organizations have concluded that, “the tightening of security measures has not, and will not reduce violence in the country. Today we live in a much more insecure country, with weaker institutions and a criminal justice system that does not work.”

One of the most questioned sectors in this strategy has been the Army, which (outside its constitutional mandate) has been deployed to carry out security tasks. In December, the Secretary of National Defense, General Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, was straightforward: “The military does not study to prosecute criminals.” And in the absence of a legal framework, “they are already thinking through whether they wish to continue to confront these groups, at the risk of being prosecuted for a crime related to human rights.” He said: “We are asking that the operations of the Armed Forces are regularized (…) We are carrying out functions that do not correspond to us, all because there is no one to do them or they are unqualified to do so.” EPN later said that the military will continue in the streets “while we achieve the objective of this subject still pending (…) to have a country in conditions of greater peace and tranquility.”

UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders with the priest Marcelo Perez, a threatened defender in Chiapas, January 2017 © SIPAZ

Certainly, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has presented an initiative for a new Internal Security Law, which seeks to normalize military participation in public security tasks. Centro Pro DH questions whether “instead of seriously undertaking the design of a program for the gradual withdrawal of the security forces, as proposed by international mechanisms in this area, the idea of generating an ad-hoc legal framework for the Army and Navy, normalizing the state of emergency, is revived.” Dozens of civil organizations, academics, and researchers asked the Chamber of Deputies “not to expeditiously approve” military permanence in public security tasks.

Finally, in January, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders, Michel Forst, visited Mexico. After traveling through the country, the Rapporteur observed the “high levels of insecurity and violence they face”, in a “complex context marked by organized crime, corruption, and state repression.” He expressed his concern that “the low-rate of successful investigations and solution of crimes committed against defenders (…) has generated a sense of widespread impunity.”

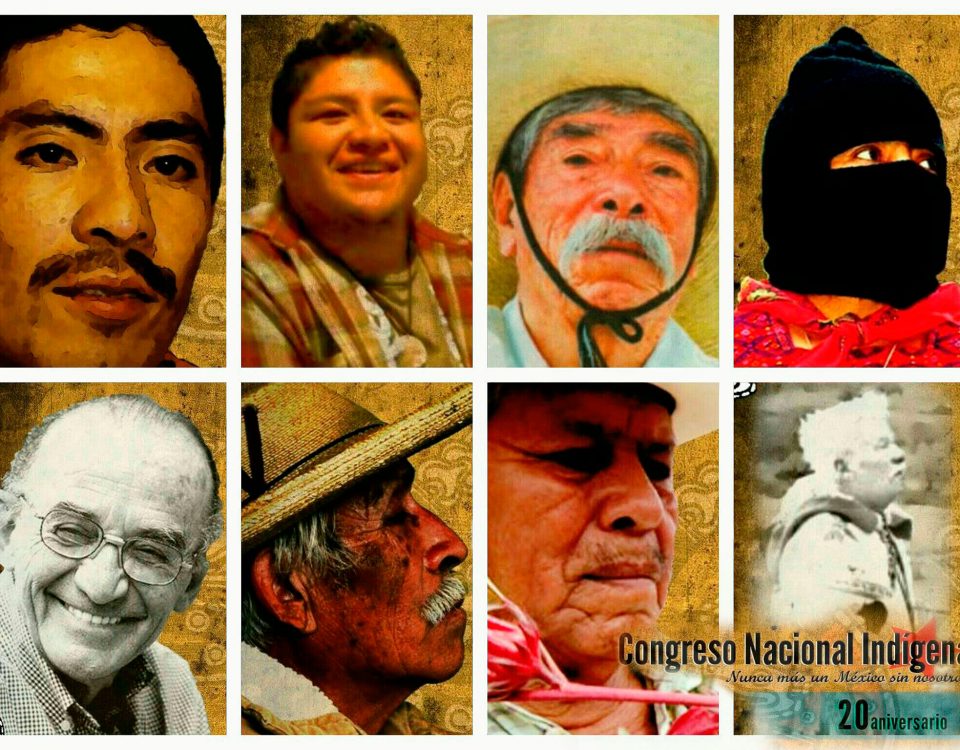

Consultation of the National Indigenous Congress: “echoes of hope” …

In November, 33 years after its foundation, the EZLN gave information about the consultation being carried out together with the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) to see if an indigenous governing council is formed and an indigenous woman is sent as a candidate for the presidential elections in 2018 (see focus). It clarified that “the CNI is who will decide whether or not to participate with one of their own delegates, and in that case, it can count on the support of Zapatismo “.But, “No, neither the EZLN as an organization nor any of its members will run for a “popularly elected office” in the 2018 elections. No, the EZLN will not become a political party. No, the EZLN will not present an indigenous Zapatista woman as a candidate for the presidency (…). No, the EZLN has not “altered its course” to any degree, nor has it reoriented its struggle to the institutional electoral path.”

On December 2, the CNI and the EZLN denounced several attacks and harassment: “The fears of the powerful, the extractive companies, the military, and the narco-paramilitaries are so great that our consultation is being attacked and harassed in the places where our peoples are meeting to discuss and decide the steps to take as the CNI.”

In December, the CNI and the EZLN confirmed the decision to “name an Indigenous Governing Council with men and women representatives from each one of the peoples, tribes, and nations that make up the CNI. This council proposes to govern this country. It will have an indigenous woman from the CNI as its spokesperson, (…) that will be an independent candidate to the presidency of Mexico.” The consultation had already been conducted in 525 communities of 43 peoples in 25 states. 430 of them approved the proposal. The constitutive assembly of the Indigenous Governing Council will be held in May in Chiapas.

GUERRERO: The wave of violence and impunity continues

In December, the CNDH and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico carried out a mission to meet with victims, human rights defenders, and authorities in Guerrero. They pointed out “the situation of insecurity in the State, the impunity in cases of human rights violations, particularly disappearances, lack of access to justice, repeated threats against human rights defenders, and internal forced displacement.” Proceso magazine emphasizes: “rampant narco-politics, the struggle between cartels, the absence of the rule of law, murders and kidnappings persist even after a joint interstate operation, the tragedy of Ayotzinapa, and thousands of authority discourses and promises.”

XXIº Anniversary of the Regional Coordination of Community Authorities – Community Police (CRAC PC), San Luis Acatlán, October 2016 © SIPAZ

In November, the body of Irineo Salmeron Dircio, Coordinator of the Liaison Committee of the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities, Community Police (CRAC-PC) was found in Chilapa. Civil organizations noted “it is a direct attack on the activities of the CRAC-PC.” They expressed that “it occurs in the middle of a wave of insecurity and violence that reigns in different areas of Guerrero, such as in Chilapa and Tixtla, circumstances that would give life to the CRAC-PC and for which the organization has been the target of attacks and harassment by both organized crime groups and by state authorities themselves who criminalize their normative defense systems.”

An example of this is that December marked three years of the imprisonment of the leader of the CRAC PC, Arturo Campos Herrera. The Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center denounced once again that, “the plan of his arrest was to demobilize the CRAC-PC (…) and to place their most combative leaders in high security prisons. (…) The instruction was to avoid having an adequate defense and generate fear among the same social organizations that are in solidarity. (…) he has succeeded in proving his innocence in four criminal cases of the seven that were filed against him. (…) However, maintaining Arturo Campos in prison for being a voice that has roots among indigenous peoples has weighed more.”

XXIº Anniversary of the Regional Coordination of Community Authorities – Community Police (CRAC PC), San Luis Acatlán, October 2016 © SIPAZ

Some of these peoples are still mobilized to defend their lands. According to Tlachinollan, of the 44 mining concessions in the Costa Chica-Montaña zone, 22 were canceled by mining companies themselves. The Regional Council of Agrarian Authorities in Defense of Territory reported that the concessions were delivered without the approval of the people, who were not even informed. These do not allow the workers of the companies to travel, even for exploration. On the other hand, between the Costa Grande and the Tierra Caliente, dozens of settlements and ejidos are abandoned or in the power of organized crime. The Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon Regional Human Rights Center emphasizes that “in all these localities there are several mining concessions that could not be installed because of the ejidos and towns that resisted.”

As elsewhere, defense has a risk and cost. For example, the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP) denounced in a press conference 40 arrest warrants are still standing against the same number of communal opponents of La Parota dam, in addition to 30 others that already existed,.

Impunity remains the norm even in such high profile cases as the forced disappearance of 43 students at the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa (2014). Despite the difficulties, the parents of the 43 continue their process of demanding justice and truth. After six months of suspending the dialogue with the government, they declared that they would meet with the Attorney General of the Republic in February.

CHIAPAS: between impunity and a new context of war

In November, a pilgrimage was held in Palenque to demand justice in the case of the Viejo Velasco massacre, municipality of Ocosingo (2006), which had a toll of “four extrajudicial executions, one illegal detention with acts of torture, four forced disappearances, and the eviction and forced displacement of 20 men, eight women, five boys, and three girls.” They recalled that “the objective … was to plant terror so that the families of the community (…) would abandon their lands, within the framework of the regional agrarian conflict in the Lacandon Jungle itself, which, by state policy and under the ecological pretext of “ensuring the conservation of the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve”, was transformed into an intense process of territorial dispossession, under mechanisms of forced relocations and violent evictions of more than thirty indigenous villages.”

Press conference five years since the forced displacement of families from Banavil, Tenejapa municipality © SIPAZ

December marked five years of the forced displacement of four families from the community of Banavil, municipality of Tenejapa, by priistas of the same location. The Fray Bartolome de Las Casas Human Rights Center (CDHFBC) reported that: “it has carried out constant interventions (…). However, to date [the authorities] have not followed up on commitments (…), on the contrary, they have acted inefficiently with zero results in the investigation.”

In the wider context of forced displacement, they denounced: “To the already historical figures of the forced displacement of communities that from 1994-2000 could not return to their territories because of threats from paramilitary groups; hundreds of displaced are added in a new context of war, of the violence of factional powers that in the coexistence of governments, companies and organized crime are destroying the life of the peoples and community in general, wrecking the social fabric, having as a final aim territorial control, and dispossession as well as the elimination of the autonomous organization of indigenous peoples.”

In December, the 19th anniversary of the Acteal massacre was commemorated, in which died “45 indigenous Tsotsiles (…) by the PRI paramilitary group of Chenalho, who acted with the consent and tolerance of the Mexican authorities, in accordance with a State policy of counterinsurgency clearly designed in the Chiapas 94 Campaign Plan,” the CDHFBC recalled.

In regards to human rights defenders, in November, the Simojovel Believing People announced the reactivation of threats and attacks against its members and the priest Marcelo Perez Perez. They have been organizing for several years to demand peace and security in their municipality. In December, the offices of the Casa de Apoyo a la Mujer Ixim Antsetic (CAM) in Palenque were raided. In January, the Digna Ochoa Human Rights Center denounced surveillance and harassment in the Progresos ejido, Pijijiapan municipality, and at the military checkpoint in the Tonala-Pijijiapan road section.

A state mobilized in defense of land, territory, and autonomy

Pilgrimage of the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory (Modevite) at the entrance of San Cristobal, November 25, 2016 © SIPAZ

In November, after a 12-day walk through 11 municipalities in the North, Jungle, and Highlands regions, thousands of pilgrims arrived in San Cristobal de Las Casas, where they denounced the insecurity they experience in their communities. They belong to the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory (MODEVITE), “composed of 10 parishes from 11 municipalities and 1 ejido” whose objective is “to organize and encourage the indigenous peoples of the area to build our autonomy as indigenous peoples and defend our Mother Earth.” They met with organizations that spoke at the International Day against Violence against Women in San Cristobal de Las Casas. Within this context, a First National Feminist Congress was also held in this same city. The activists and organizations present questioned the Declaration of Alert of Gender Violence (AVG) issued a week earlier in some municipalities of the state, calling it “incomplete, discriminatory, and insufficient.”

Also in December, the “Forum on Defense of Land, Life, and Territory” was held in Amador Hernandez, municipality of Ocosingo, which pronounced itself “against the implementation of the Environmental Gendarmerie and its entry into our territory.” It affirmed that it seeks “to guarantee the entry of transnational companies dedicated to the extraction of natural resources to the benefit of big capital”. On the same day, President Enrique Peña Nieto was in the Lacandon Jungle in the framework of an activity as part of the COP (Conference of the Parties) 13 under the motto “Integrating biodiversity for well-being.” He gave instructions to avoid regularization of irregular settlements and to ensure that no extractive activities are carried out in the region.

In spite of the threats, in December, thousands of indigenous people from Tila celebrated the first anniversary of the expulsion of the municipal council and the construction of their ejido self-government. Since then, “a handful of Tila settlers are pressuring the Attorney General’s Office and the government to send their repressive forces to execute the more than 20 arrest orders against the ejido authorities and ex-authorities (…) and others who have no connection.”

Pilgrimage of the Believing People in San Cristobal de Las Casas on the 5th anniversary of the death of Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia, January 2017 © Frayba

Finally, on January 25, members of the Believing People of the Diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas held a pilgrimage on the 5th anniversary of the death of Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia and also for the 25th anniversary of the Diocesan Coordination of Women (CODIMUJ). They confirmed their goal of “building autonomy in our communities, restoring our governance structure” and “maintaining our resistance to the projects of death.”

OAXACA: New governor, same old problems

In the morning of December 1, Alejandro Murat Hinojosa (PRI) took office as the new governor of Oaxaca. He had won the election with only 18.8% of voters. The event took place in an alternative seat to the Congress, which was taken over by Section 22 of the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE), which also organized 37 roadblocks in the state. Section 22 described this inauguration as “spurious and without consensus(…)that comes hidden from the Oaxacans, hungry for power and ambition of authority.”

About 20 organizations denounced that “the immediate objective of the PRI is to maintain the route of the imposition of structural reforms, which allows them to exploit natural resources (…), obtain cheap labor (…) take resources from state resources regardless of public services (…); generate more infrastructure for the movement of goods (…) and advance the liquidation of indigenous, social, trade union, and human rights resistance.”

There are several processes and mobilizations in defense of land and territory in the state. In November, in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a process of articulation began to establish collective appeals for legal protection (amparos) against the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) corresponding to the area. They argue that there has been no information or consultation, and that it seeks to spark foreign investment projects that would generate a displacement of the peoples’ lands and dispossession of natural assets.

Also in November, the community of Magdalena Ocotlán prevented a consultation “rigged” for the expansion of the mining project promoted by the Cuzcatlan company, a subsidiary of the Canadian Fortuna Silver Mines. They pointed out that this action, carried out in complicity with the authorities, is “an act of provocation, as we have defined not to accept any mining project since 2005.”

In January, the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Isthmus (UCIZONI), which includes 12 municipalities of Tehuantepec, demonstrated in Mexico City against the Salina Cruz gas pipeline project to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz saying they rejected “all the consultations they [companies] want to do because they are being done based on their sole interests.”

This defense of land and territory carries a risk to those who lead it. In January, human rights defenders in Oaxaca reported to UN Special Rapporteur Michel Forst an increase in aggressions in the last decade and the lack of interest of the authorities to guarantee the right to defend human rights. As for freedom of expression, the situation remains equally critical. In January, La Perla de la Mixteca community radio reporter, Soraya Abigail Arias Cruz, received a death threat by a telephone “after questioning the act of The 2014-2016 administration of the city of Tlaxiaco, headed by PRD Alejandro Aparicio, now a local deputy.’ Article 19 recalled that, “Oaxaca ranks as one of the most violent [states] for journalists.”

All this occurs in a context of almost total impunity as in the rest of the country, which is why actions continue. In November, the Indigenous and Campesino Front of Mexico (FICAM) took over the Huajapan de Leon Court because it considers that its actions maintain unpunished the murder of Bety Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola while participating in a humanitarian caravan to San Juan Copala in 2010.