SIPAZ Activities (May – August 2003)

29/08/20032003

31/12/2003September marked seven years since the suspension of talks between the federal government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN). On November 17th, the EZLN also celebrated twenty years of existence. It decided to celebrate the event internally, although it invited both national and international civil society to participate in the events that various organizations, both within and outside of Mexico, were holding related to these anniversaries.

Nearly ten years after the armed uprising, in January of ’94 in Chiapas, the possibilities of a resumption of a process of negotiation seem every day more remote. Each side positions itself depending on strategies, times and interests that are clearly different.

At the national level, the agendas of the political parties are focused on the reforms of energy (electricity and petroleum) and ownership of land, already in the context of the race for the next presidential elections (2006). The conflict in Chiapas is not a priority. The Secretary of the Interior, Santiago Creel, in his visit to Chiapas in October, confirmed in respect to this topic, that “there is a policy that hasn’t varied since the beginning of the administration, which has included the presentation of the Cocopa initiative, the release of prisoners connected with the EZLN, (and) the relocation of seven military bases”, referring to the three conditions raised by the Zapatistas at the end of 2001 for resuming the dialogue. Although the government considers these conditions accomplished, the indigenous rights reform finally approved by the Congress of the Union in 2001 was not recognized by the EZLN, which considers it a treason against what was established in the San Andrés accords in 1996. During his visit, Creel also commented that they are waiting for the responses from state congresses about the constitutional reform, “to make an evaluation” and to present a package of legal initiatives before the Congress of the Union.

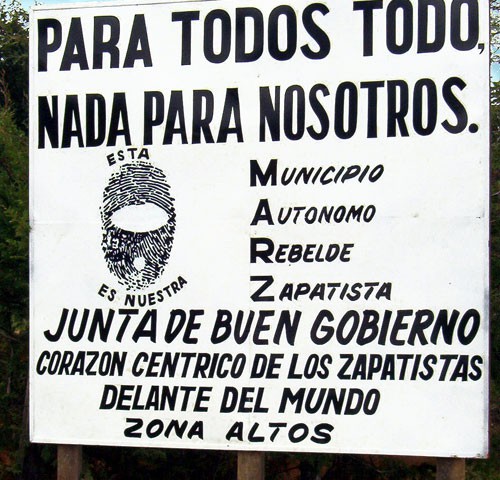

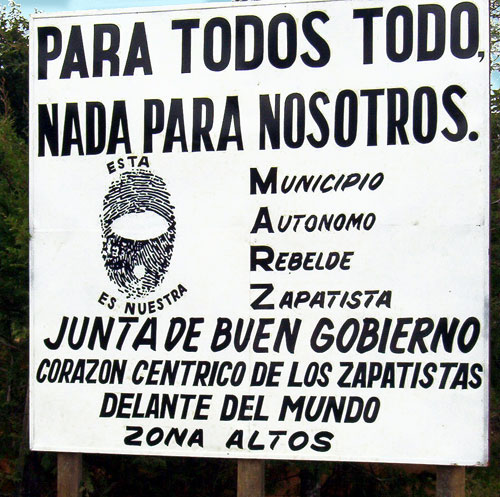

On the other side, the EZLN has suspended all contact with the government and political parties. They have declared that the San Andrés accords will be “applied in the rebel territories” through their actions. The “Juntas of Good Government” (JBG), formed this past August by delegates of the Zapatista Autonomous Rebel Municipalities in five Caracoles (see SIPAZ bulletin, August of 2003), represent a new stage in the construction of Zapatista autonomy. It is a long-term gamble, challenging the “official” power by assuming the government’s role in all its scope (education, health, justice, development, etc.).

Repositioning of the official discourse “post caracol”

Faced with the new Zapatista strategy, the discourses of the government have leaned towards the notion that the Juntas of Good Government could be able to frame themselves in the Constitution. The state and federal government have been “playing hot potato“, with neither of the two levels of the government seeming to want to be stuck with responding to the new situation. Certainly, in the indigenous law approved in 2001 the definition of both the scope and extent of autonomy are the responsibility of the states (which was one of the points of regression in comparison with San Andrés).

Nonetheless, in September, the Commission of Indigenous Towns and Communities of the Congress affirmed that “it should be the responsibility of the federal government, and not of the local Congress to attend to the new form of Zapatista organization, because it is a national issue”, in that, in 1994, the EZLN declared war on the federal government.

For his part, in October, the governor of Chiapas, Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía recognized that the efforts of the EZLN to create the Juntas of Good Government are “interesting” and that “they don’t change the life of the constitutional bodies, the town councils, or the state government”. He pointed out that the state of Chiapas, differently from other governments in times past, has been and will continue to be respectful of the decisions of the Zapatista communities.

It waits to be seen if this federal and state posture can be maintained over an extended period of time in a state where so many hot spots can burst into open violence or, to use the words of Samuel Ruiz, archbishop emeritus of San Cristóbal de las Casas, in a situation of “formal stagnation with real damage.” Even more so when the majority of the communities in the state are divided, despite the Zapatista offer to also be of service to non-Zapatistas living in their territories.

Nonconformity through redefinition of territories

The creation of the JBG promises a reworking of relationships, as much within as outside of the Zapatista territories. Despite the conciliatory message towards non-Zapatistas, the redefinition of said territories has not escaped causing nonconformity on the part of other social actors.

The majority of the cases have arisen in the northern zone of the state, where the Zapatista presence was not that visible until the creation of the Caracoles. In September, the JBG “New Seed that is Going to Produce” (Roberto Barrios) denounced violent acts which had occurred in different communities in the region “by groups positioned on highways, and at exits and entrances to different autonomous communities.” These acts included blows, threats of dislocation, and signs shot at or destroyed, principally in the official municipalities of Tila, Sabanilla and Palenque.

At the end of September, similar situations presented themselves in Ocosingo (Jungle). Another point of tension has been the construction of highways in the Zapatista zones of the municipalities of Chilón and Ocosingo, where the Zapatistas have been requesting payment from the construction companies for working in their territories.

Risk of the escalation of violence

The denunciations of groups considered to be paramilitaries are also worrisome. Campesinos in the region Monte Líbano and Taniperla (Jungle) announced that they have once again seen armed men, wearing black uniforms, undergoing movements and practices. At the end of October, in a communication from the Caracol “Whirlwind of Our Words”, the JBG “Heart of the Rainbow of Our Hope” denounced attacks by the group Los Aguilares, in the community K’an Akil, in the autonomous municipality of Olga Isabel (in the official municipality of Chilón). The denunciation stated “there have been recorded detentions, and this group has come to provoke and frighten in the roads of this region, to close the path to the stream where the women need to wash clothing and bathe, which is the only place that they can use.”

In October, a hundred Zapatista supporters belonging to the autonomous municipality Francisco Gómez made a stand in the community of San Manuel, Ocosingo. The inhabitants of that town reported that on October 16th, a group of 15 PRI supporters harvested almost a hectare of a field, which was property of the community. Given the situation, the inhabitants of San Manuel are positing a permanent watch.

The challenges of the JBG related to questions of justice

The existence of parallel structures, the official structures on the one hand and the Zapatista ones on the other, acquires a greater complexity in terms of the administration of justice, because of the existing plurality in the “Zapatista” territories. This situation raises questions around the difficulty and legitimacy of “governing” those that haven’t elected you as an authority.

One of the first cases was rooted in the detention of Armín Morales Jiménez, on September 2nd in San Pedro Michoacán, by Zapatista militants “for appropriating a vehicle that wasn’t his” according to the Zapatista version. In response, members of the Independent Headquarters of Agricultural Workers and Campesinos-Historic (CIOAC-H) retained seven people, two of whom belonged to Zapatista communities. Forty-eight hours later, five of them were liberated. The ultimate two (Zapatistas) were held for nine days before they were freed. Despite their liberation, the tone of the situation continued to escalate until on October 12th, Armín Morales was liberated, supposedly because the state government paid the fine of $80,000 pesos ($8,000 dollars) to the owner of the vehicle Armín Morales Jiménez had illegally appropriated. The intervention on the part of the state government in the matter was quite controversial, in that it recognized the de facto legitimacy of the judgment passed by the Junta of Good Government.

In the beginning of October, the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Center for Human Rights (CDHFBC) suggested that “as long as the normative systems of the indigenous people are not recognized, it is assured that problems of this type will appear making the rights and just demands of these people vulnerable and further weakening the social fabric.”

Another case at the beginning of September called this to our attention. Three indigenous people, from the community Flores Magón, in the municipality of Teospisca, were detained for transporting wood and accused of ecocide, “premeditated damage to the ecology” according to the Penal Code. These people had authorization from the autonomous municipality of Miguel Hidalgo to exploit and transport the wood, which for the first time, was presented before the trial judge by the president of one of the autonomous Zapatista councils. The indigenous people were liberated in a few days.

The occurrence of these different cases begins to illuminate two types of scenarios in terms of the application of justice in plural territories: acceptance and construction of the legitimacy of the JBGs or conflict between the two parties and eventually with the “official” system of justice.

Montes Azules: tense calm

Although there haven’t been any recorded acts of violence in the Montes Azules biosphere in the last few months, contradictory discourses on the part of different government requests have contributed to a high level of tension. While the Secretary of Agrarian Reform stated that there would be no more violent dislocations in the zone, the Federal Prosecutor for the Protection of the Environment (PROFEPA), wouldn’t discount the possibility of applying the law with “a firm hand” and utilizing public forces against people located in these lands.

In October, the Rural Association of Collective Interest (ARIC-Independiente), which is negotiating with the government the recognition of various populations situated in Montes Azules, questioned what was expressed by PROFEPA: “Instead of contributing to a solution to the problems, they make it worse, because they want to say that in the government there are groups that are promoting dislocation by force, and this discredits the negotiations and signifies that the authorities don’t have the true political will to resolve the situation.”

On the other hand, Felipe Villagrán, the ex-employee of the World Bank who is representing the Lacondes of Lacanjá Chansayab and the inhabitants of Frontera Corozal and Nueva Palestina, met with Governer Pablo Salazar Mendiguchía and different state and federal civil servants. He requested that “they implement immediate patrols day and night by the Mexican Army and a detachment in Paraíso” (where a Zapatista community is located) as well as “the authorization to import low caliber arms to protect the crops of the community members.” (La Jornada, 10th of November)

Militarization and mobilizations against the militarization

Following the creation of the Juntas of Good Government (JBG) in the autonomous Zapatista municipalities, there was a reported increase in troop movements (patrols and military checkpoints) in different zones of the state, principally in the so-called conflict zone. On the other hand, in the last several months, we’ve seen a growing rejection of the military presence – a tendency that is not exclusive to Zapatista communities.

Even though in the majority of the cases the rejection is non-violent, one perceives the tension rising. In this manner, in the beginning of September, more than a thousand indigenous people of the Chenalhó municipality detained thirty-five members of the Mexican Army so that they would pay for the damage caused by their trucks on the Terrecería highway. They were released on the condition that the Mexican Army would provide material to fix said highway, at a cost of $15,000 pesos ($1,500 dollars).

On the other side, in October, indigenous EZLN sympathizers from the community of Yulumchuntic, in the municipality of Chalchihuitán (Altos), detained for several hours thirty members of the Mexican Army who were patrolling to fight the growth and harvest of drugs. There are several versions of the story. People say that the indigenous people took off the soldiers’ boots, disarmed them and forced them to walk across the basketball court. Nonetheless, the JBG “Central Zapatista Heart Opposite the World” said that they only stopped them outside of the school of Jolitontic. They told the soldiers that the Zapatistas reject the presence of the military in their localities, and peacefully made them leave, because the military had installed a camp in autonomous territory. The soldiers were freed after several hours, by promising the community that they would not pass through the zone, paying a fine ($20,000 pesos or $2,000 dollars) and through the direct intervention of the commander of the 31st military zone.

In October, during the Special Conference on Hemispheric Security, which took place in Mexico City, the members of the Organization of Americans States (OAS) committed themselves to cooperating against security threats. They left each state free, however, to identify its own security priorities and define strategies, plans and actions to face the challenges imposed by the new world situation. They stressed that peace is strengthened when its human dimensions are studied, and when respect for dignity, human rights, fundamental personal liberties, economic and social development and the fight against poverty, sickness and hunger are all promoted.

Under the auspices of continuing the Hemispheric Encounter Against Militarization which took place in May, the Meetings about the Impacts of Militarization “For demilitarization, we unite our struggles” took place from November 18th to the 23rd in San Cristóbal de Las Casas. It was another event in the framework of a week of struggle in which protests and marches across the continent took place in unison.

Shared Struggles

The solidarity towards the Zapatista movement was heard in October, in the Meeting of Indigenous Nations in Mexico. Some 200 representatives of indigenous organizations and communities from Oaxaca, Michoacán, Jalisco, Veracruz, Mexico State, Sonora, Mexico City, and Puebla, as well as representatives of non-indigenous social groups reiterated that the indigenous peoples of Mexico “recognize and elevate the San Andrés accords as our indigenous constitution and we demand the approval of the Cocopa law” and that it was “a treason by the legislators” that it wasn’t done. They also made a pronouncement in favor of the Juntas of Good Government announced by the EZLN in Oventik.

The EZLN demonstrated their willingness to be a part of an alternate world when, on October 26th , Subcommandante Marcos sent a recorded message to academics, intellectuals, and leaders who participated in the meeting “In Defense of Humanity,” which took place in Mexico City. The objective was to form a bloc in defense of the rights of the people, and against neoliberalism and globalization. He advised that the fight against the globalization of power is a question of human survival.