2003

02/01/2004

UPDATE: Mexico-Chiapas, Reports on the Governments

30/09/2004UPDATE I: Chiapas, Hot spots multiplying in high tension context

Certainly, Chiapas no longer occupies the first pages of national newspapers like it did in the first years after the armed uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in 1994. Nevertheless, when reviewing the other pages of those national or local periodicals, one cannot help being alarmed to read of the multiplying hot spots that could lead at any moment to the escalation of violence. It is even more alarming if we consider that most of the reasons for this escalating tension correspond to the structural factors that originally generated the uprising.

From the Highlands…

The first violent event of recent months happened last April 10 in the municipality of Zinacantán, where hundreds of Zapatista supporters participated in a peaceful march to remember the anniversary of Emiliano Zapata’s death. After the demonstration, they distributed water to the communities that had been deprived of this service by the PRD (Democratic Revolution Party) municipal authorities. They were ambushed by supporters of the PRD, resulting in dozens of wounded and 125 displaced families, who were unable to return to their communities for 15 days (see separate article in this same report).

There also exists a conflict with similar roots in the municipality of Tenejapa. Here disagreements over property and the use of spring water could also result in violence, according to inhabitants of one of the affected communities.

By the end of May, the council of Polhó (Chenalhó), announced that “the armed groups that are linked to the PRD government of Zinacantán, that have previously acted, are allied with at least one sector of the paramilitaries of Chenalhó. They were never disarmed, and have not stopped operating, threatening and maintaining thousands of indigenous zapatistas in exile since 1997 “.

To the jungle…

The most talked about hot spot in the jungle is the biosphere reserve of Montes Azules, where the threats of eviction continue and the relocation of more than 30 communities is pending. Federal and State institutions claim that they have privileged lines of dialogue with “the irregular” settlements. In March, 10 communities located in Montes Azules and united in the Indigenous Communities Union of the Chiapas Jungle, refused to engage in a dialogue with the Federal Department of the Agrarian Reform on their possible relocation. They say that they will not accept “more supposed dialogues and negotiations in which serious commitments and agreements are not reached”.

Other public declarations sound even more ambiguous. In April, for example, Jorge Nordhausen (PAN Party for National Action) of the Environment, Natural Resources and Fishing Commission of the Federal Senate proposed to continue the evictions in Montes Azules, “in order to recover the order and the legality in the biosphere reserve located in the Lacandon Jungle”. He emphasized that the evictions “do not consist of arbitrary measures, but in actions founded on the law, motivated by those invasions that harm the nation’s natural patrimony “.

In May, the PROFEPA (Federal Office of Environmental Protection) assured that it had obtained 13 agreements of relocation and five of regularization that would become effective in June.

In Las Cañadas, strong, mutual accusations between the organizations of the zone took place in April. The Council of Good Government, “the Path of the Future,” denied that the Zapatistas are creating police groups. On the contrary, they announced that PRI party members and members of the Rural Association of Collective Interest (Independent ARIC) are the ones who had been placing checkpoints around Ocosingo during the last two months, regardless of the Zapatistas.

From the Northern zone to the Coast

At the end of April, the Council of Good Government, “Seed that is going to produce,” accused presumed paramilitaries linked to the PRI, of attacking EZLN family-base supporters of the Tiutzol community in the municipality of Tila (Northern zone).

The conflicts continue surrounding those in resistance to making payments to the government for electricity. There have been reports of blockades (Tapachula) and detention of employees from the Federal Commission of Electricity, CFE (Coast, Northern zone). Nevertheless, at the end of May, the South-Southeastern Division Manager of the CFE assured that 90 percent of the people in the Coastal Region already accepted the preferential payment program, “Better Life” (See March 2004 SIPAZ report). He affirmed that the conflicts that have occurred are “small outbreaks” and the CFE will continue to suspend the electricity of all those who refuse to pay.

… … … … … …

Community Conflicts or The Tip of an Iceberg?

Some see these violent outbreaks as part of inter or intra community problems. During a visit to Chiapas in April, the secretary of Interior Santiago Creel said that “Chiapas has stopped being a headache for the federal government” and that “it has political stability” regardless of the confrontation in Zinacantán. He described this confrontation as an “incident“.

However, others see these facts as indicators of a situation of a greater magnitude. The Commission of Support to the Unity and Reconciliation of Communities (CORECO) affirmed that “what happened on April 10th was not a simple quarrel, nor pure consequence of the inability of the State and municipal governments to solve a population’s need. It is not the result of the aggravation of the conflict due to the existence of two legal frameworks either. The ambush, the aggression, the violence, the threat, and the harassment towards the march and the communities in resistance in Zinacantán, happened, once again, as an attempt to force the supporting bases of the EZLN to resign their political affiliation”.

Deputies of the Concord and Pacification Commission (COCOPA, created by the legislative branch to help in the dialogue between the EZLN and the government) affirmed that the events of Zinacantán reflect the “discarding” of the Chiapas theme from the federal government’s agenda.

Luis H. Alvarez, commissioner for the peace in Chiapas in the federal government, said, “the EZLN has an important responsibility to generate a space of political negotiation that will allow for the avoidance of greater conflicts and indigenous bloodshed. It is necessary that the EZLN admits once and for all that it is necessary to reopen the dialogue with the governmental authorities to obtain the basic agreements that permit the peaceful coexistence with the rest of the nation “.

In June, the Chair of the PRD in the House of Representatives said that it will ask Luis H. Alvarez to appear before the commission, considering that he weakened his ability to do his assignment because during his visits to Chiapas he delivered sheet metal roofing and other supplies to the population that has deserted or are against the zapatista bases. The PRD member Gerald Ulloa, stated that the distribution of materials by the commissioner made him more an instrument of the government to undermine the Zapatistas’ bases, which does not help in the reopening of the dialogue, but rather it reduces his ability to negotiate.

… … … … … …

Escalating Tensions

Behind these violent events, multiple factors exist.

Sequels to years of war

To the social, political, and economic marginalization that existed for the indigenous communities of Chiapas before 1994, one needs to add the consequences of a low intensity war carried out in the region in recent years, whose more visible face is the permanent militarization of the territory within Chiapas. Another consequence has been the decomposition of the social web that has created intra-community and inter-community conflicts. Increasingly, culture of intolerance and a tendency to settle differences (ideological, political or religious) with violence predominates.

At the beginning of June, the Human Rights Center Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas announced that the situation of more than 12,000 displaced people in Chiapas, due to the armed conflict, continues to be an unresolved subject. It indicated that, although some have sought to negotiate with the Government, none of the cases have resulted in the granting of land, nor lead to investigations into those responsible for the displacements.

Days later, Emilio Zebadúa, PRD federal deputy, stressed that the displaced people of Chiapas are in a situation of “high vulnerability” due to the withdrawal of the International Red Cross Committee (CICR) who benefited this sector. Zebadúa questioned why the federal government has not fulfilled the recommendations in favor of the displaced people issued a year ago by Francis Deng of the United Nations.

Pre-electoral frame

Another factor behind the increase of the social tension has to do with the October 3rd local elections in which 118 mayors and 40 deputies will be elected. The fight for power (candidacies and elections) intensifies the atmosphere of conflict.

On the federal level, even though the next federal elections will not be until 2006, the political agenda is already focused towards them and rife with scandals, internal fights in the parties, and disqualifications.

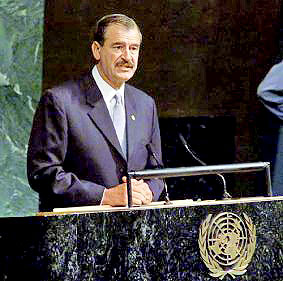

Within the National Action Party (PAN), which is presently in power, there has been friction between President Fox and his possible successor within the party, Felipe Calderón, Secretary of Energy. Calderón announced his candidacy for the Presidency during the III Summit of State Chiefs and Governmental Heads of Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union (EU). President Fox then forced him to resign his current position so that he could dedicate himself to the political campaign, thus reflecting the differences between the different ‘panistas‘ families.

Within the framework of the opposition parties, the case with the most coverage has been the conflicts between the federal government and the present head of Government of the Federal District, Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, a possible PRD candidate to the presidency.

Conflicts in Legal Spaces

“Mordaza” (Gag) Law

On February 17th reforms to the penal code that refer to crimes against honor were approved in Chiapas. These reforms allow sanctions of nine years of jail and fines up to one thousand days of minimum wage to be imposed for a crime such as slandering a public official. Organizations defending human rights, groups of journalists, and the civil society demonstrated their opposition to these reforms, arguing that they are contrary to the rights to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as, to the right to information. In addition, they emphasized that the reforms go against legal documents signed by the Mexican government, like the Universal Declaration of the Human rights and the American Convention of Human rights. Nevertheless, these reforms became effective at the end of May 2004.

CEDH

Another situation that caused concern among human rights organizations in Chiapas, in terms of resources that public institutions should offer their citizens, has to do with the controversy that arose between the National Commission of Human rights (CNDH) and its state counterpart (CEDH). According to the CNDH, CEDH failed to enact recommendations issued by the national body, and this failure allowed municipal police of Comitán, who had attacked 66 people during an eviction in 2002, to go unpunished.

In June, the Congress of Chiapas allowed an accusation for contempt to be presented by the CNDH against its state body. The local ombudsman, Pedro Raul Lopez Hernandez, asked the legislators to respect the right of the CEDH to have a hearing before taking other action on the matter.

Law on DDHH

In April, an initiative at the federal level to reform the constitution on human rights issues also generated controversy. The member organizations of the Liaison Committee between the federal government and the Office of the High Commissioner of the United Nations for the Human Rights (ACNUDH), announced that, in spite of touching on key aspects, the reform moves away from the letter developed jointly and the spirit of the proposal, undermining the established dialogue process. (For more details, view the site of the Human Rights Center Miguel Augustin Pro Juárez).

The organizations of the Liaison Committee called into question President Fox’s declarations (in the sense that nobody can question the government for not respecting human rights): “important evidence exists that contradict his affirmations. This evidence can be found in the Diagnosis of the High Commissioner of United Nations for the Human Rights (ACNUDH) and in the numerous complaints received and documented by the National Commission of Human Rights and international organizations. As well as, the greater number of violations that remained undeclared due the lack of confidence created by the ineffectiveness of both the judicial and non-judicial institutions responsible for the protection of human rights and confronting these issues. The situation urgently demands no more speeches distant from reality but an actual State policy that assures respect, dependability and protection of human rights “.

At the end of May in its 2004 report, Amnesty International affirmed that the efforts of President Vicente Fox’s government to guarantee respect for human rights have been “insufficient” to restrain “frequent and generalized violations”. This report declared that the “structural failures” of the penal justice system continue to be the key cause of the violations of human rights and impunity. In addition, it indicated that in indigenous communities, discrimination, marginalization, and conflicts continue to cause multiple violations of human rights. The report points out that in June 2003 AI was invited to Mexico to resume the negotiations with the EZLN and to reform the “controversial” 2001 legislation on indigenous rights. Also, it mentioned that there is a great concern about the danger that the Puebla-Panama Plan represents for the indigenous communities in southern Mexico, since it threatens to violate the economic, social, and cultural rights of these communities.

By the end of May, representatives of civil organizations met with the Secretary of Interior, Santiago Creel, and obtained a series of agreements to guarantee the continuity of the dialogue with the government.

SOCIAL PROCESSES and OFFICIAL SPACES

With regards to indigenous communities, in the middle of May, the thirteenth meeting of the Indigenous National Congress (CNI) took place in Union Hidalgo, Oaxaca. Delegates from the Center-Pacific region decided to ratify the San Andrés Peace Accords as the “Indigenous Constitution” and to proceed in a “peaceful rebellion” by means of exercising autonomy. Juan Chávez, purépecha of Nurio, emphasized: “there is no need to fall into continually asking the State for something that it has already denied to us (the constitutional recognition of the rights of the Indian communities with the approval of the initiative of the COCOPA Law). We do not have to ask the government for permission. That demand was left behind with the creation of the Caracoles (Snails) in Chiapas and with the autonomous municipalities like Xochistlahuaca (Guerrero) and with what is happening in Hidalgo Union (Oaxaca) and Tlalnepantla (Morelos)“.

On May 28th, the summit of Heads of State and Government of Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union with representatives from 58 countries began in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico. Several “antiglobalization” social forums took place simultaneously (see separate article). Unfortunately, in the press very little of the content of the discussions was rescued due to the fact that the protest march that culminated several days of work ended with acts of violence. Several organizations that were present declared that the intensity of the police repression surpassed the safety measures that could be established to defend themselves from the small groups within the march.

45 young Mexicans were detained. Eight foreigners were deprived of their freedom and finally deported from the country. Human Rights organizations condemned the abuses, humiliations and violations to their rights of access to justice and the protection of their physical integrity due to what they were put through. One week later, the Mexican prisoners were formally charged for crimes of rioting, gang actions, resistance or disobedience, attacks on the communication lines, injuries, robbery, and damage.

Lastly, in Declaration of Tepeaca (State of Puebla), the Mexican Gathering for Alternatives of Life and People was celebrated from June 4-6 in preparation of the upcoming Mesoamerican social forums in the month of July, which will take place in El Salvador. Representatives of 112 social organizations from the whole country met together. They rejected the neoliberal policies imposed by the President, as well as their direct consequences. They reiterated their fight for the autonomy of the indigenous communities and therefore, for the fulfillment of the San Andrés Accords. They proposed the creation of an Alternative Plan of Life for the Mesoamerican Communities based on the dignity of their people, their culture, and mother Earth.

Community Conflicts Or The Tip Of An Iceberg?