Chiapas presently finds itself in a pre-election context given that on October 3, 118 municipal mayors and 40 state deputies will be elected. In spite of the profusion of posters, slogans and promotional events, the national framework partially diminishes the relevance of these local power groups and their election process. It appears, rather, that what is anticipated to be at stake are the next federal elections in 2006. With this date in mind, two statements can be utilized as a sort of political barometer: the Government Report presented by President Fox in September, and a series of communiqués from Sub-Commander Marcos published in August, which represent the first reports from the Juntas of Good Government since they began one year ago.

Turbulence Surrounding The Presidential Report

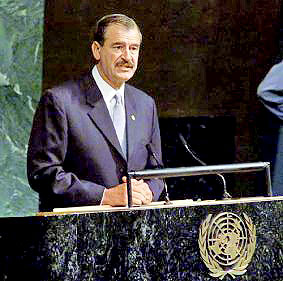

On September 1, President Fox presented his fourth Government Report to the Congress of the Union. The place where it was presented was surrounded by police and military, with metallic fences measuring more than three meters high. Outside the building, contained by police, thousands of campesinos, electrical workers, and union members protested. Within the Chamber of Deputies, expressions of discontent also predominated. The ceremony was interrupted twenty-three times by the protests of legislators from all political parties (Save the National Action Party, PAN, the President’s party). Deputies from the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD, the main leftist party) demonstrated their lack of respect for the President by turning their backs to him.

Aside from these events, the item most focused on by the press was the truce that Vicente Fox requested in order to bring about joint agreements: “The political change is showing significant deficiencies. One of the most evident is that communication between the Legislative and Executive Powers has not been as fluid as the times demand. (…) It is the responsibility of all members of the political class to prevent society from becoming disillusioned with democracy, from thinking that the struggle that lasted for so many years was in vain.”

However, others read his message “never again shall an authority be above the law” as a direct allusion to Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the present Chief of Government of the Federal District. A member of the PRD, Lopez Obrador is popularly thought to be the eventual candidate for the presidency of the Republic. A request to strip the leader of his governmental immunity is being processed by the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic. It is hoped that he will be tried for his alleged responsibility for the crimes of abuse of authority and non-compliance with a judicial mandate that ordered the interruption of construction projects on two roadways, which could impede his candidacy. This situation has generated a great deal of popular indignation, as seen in a protest by hundreds of thousands of Mexicans in Mexico City on August 29. Many PRD deputies also protested the attempt to strip Lopez Obrador of his immunity during the fourth Presidential Report.

The lack of a minimum level of political agreement with Congressional opposition has certainly made the structural reforms proposed by the President impossible. But with the early start of the succession period, other disputes have also surfaced within his own party and Cabinet. Alfonso Durazo Montaño, ex-presidential press secretary, resigned from his post, denouncing: “If there isn’t legality, equality, democracy, and impartial presidential arbitration, the 2006 elections could become a repeat of the old and harmful rounds of distrust regarding the election results. And if the elections are not resolved at the ballot box, they will be resolved in the streets.” This provoked a scandal that ended with Martha Sahagun abandoning her efforts to succeed her husband in the presidency.

In all aspects of internal politics, and in those of a more international character (relations with the U.S. and Cuba, in particular), the contradictions make it clear that the highest levels of Mexican politics (specifically the executive and legislative branches) are at an impasse.

Among many people a sense of disillusionment and distrust of the political class predominates, as was noted by the high levels of electoral abstention in 2003. The apparent macro-economic stability is not reflected in either the levels of the poverty or unemployment, nor in those basic questions that worry most Mexicans (for example, the issue of security). Nor can the profound social and political crisis behind the multiplicity of protest marches in Mexico City be hidden.

Taking Stock Of The Councils Of Good Government After One Year Of Functioning

In an extensive series of communiqués entitled “To Read a Video”, Subcomandante Marcos presented the first progress report for the Councils of Good Government that would be completed by the Councils around the middle of September.

Although the communiqués received little attention in the mass media, they are worth reviewing and are more relevant in the electoral context just described. In fact, in the first section of communiqués, Marcos describes the current political landscape in these terms: “Passing quickly over these main images of “national life” (…) provokes a sensation of chaos, anachronism and injustice. The current calendar says we’re halfway through the year 2004, but the programming at times seems to be halfway through the 19th century, and at times halfway through the year 2006.” The communiqué questions the corruption and anti-democracy of the political parties, the tendency of the political parties to move toward the right, the role of the mass media and the dysfunctional nature of the justice system.

The second part is more of a self-critique of the functioning of the Councils of Good Government. It refuses to describe the wait that some visitors have been subjected to as an “error,” explaining, “it must be understood that we are in a movement of rebellion and resistance. If we add to this many generations of victims of deception and betrayal, it can be understood that there is some natural distrust (…). What some see as bureaucratic tendencies in the Councils of Good Government and the autonomous councils are, in reality, a product of the dynamics of persistence and persecution.”

Marcos also does not recognize the rotation of the committees in the Caracoles as erroneous. He explains: “We know well that this method makes the completion of some projects more difficult, but, on the other hand, we have a school of government that, in the long term, will offer a new way of doing politics. Besides, this “error” has allowed us to combat the corruption that can be present in authority. (…) It will take time, I know. But for those like the Zapatistas who make plans for decades, a few years is not a long time.” Also, attention is being paid to the issue of representation (“the other ‘error’ that is not one”), and subsequently, the turning down of invitations or requests to support other movements.

In the end, Marcos recognizes two main failures: the lack of participation by women, and the relationship between the Zapatista political military structure and the autonomous governments.

With respect to women, he writes: “If, in the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committees, the percentage of female participation is between 33 and 40 percent, the autonomous councils and the Councils of Good government are at, on average, less than one percent. (…) In spite of the fact that the Zapatistas women have had and do have a fundamental role in the resistance, in regard to their rights, it continues to be just a declaration on paper in some cases. It is true that inter-familial violence has decreased, but this is due more to the limits on alcohol consumption than on a new culture with regards to family and gender.”

With respect to the relationship between the political-military structure and the autonomous governments, Marcos completely recognizes the limitations: “Originally, the idea we had was that the EZLN should accompany and support the people in the construction of their autonomy. However, the accompaniment has changed directions at times and become more orders than advice, more an obstacle than support (…) The fact that the EZLN is a political-military organization, as well as clandestine, continues to corrupt the processes that should and must be democratic.”

In the third part, he comments that “Old Antonio” once explained to him that indigenous people walk bent over “because they carry on their shoulders their hearts and the hearts of everyone.” He adds that, “To the two shoulders that human beings normally have in common, the Zapatistas have added a third: that of “civil society.” He gives thanks for the support that has moved them forward towards a cause, “that continues to be large: the construction of a world where many worlds fit, that is to say, a world that carries the heart of everyone.”

He stressed that this year, “people and organizations from at least 43 countries, including (…) Mexico,” visited the “Caracoles.” The Caracoles also reported income of almost twelve and a half million pesos and expenditures nearing ten million, explaining that the money was divided between the five Caracoles and the reasons for those divisions. However, the details that the Councils of Good Government themselves will give out clarify that none of these funds were used for personal gains.

The fourth part refers to what Marcos calls the “four fallacies” – arguments that have been used by groups who are opposed to the autonomous processes of the Zapatistas. The first fallacy refers to the fact that said processes can disintegrate or “balkanize” the country. Marcos emphasized that that has not been the case, even though the country is “in effect, disintegrating, but not for indigenous autonomy, but for an actual internal war, for the merciless destruction of its foundations: the sovereignty over natural resources, social politics and the national economy. (…) In short, the federal government has given up its functions, and the national state is unsteady due to the attacks from above, not from those below.”

Faced with this situation, he proposes “…refounding the nation. With a new social pact, new Constitution, new political class and new way of doing politics. In short, what is missing is a program of struggle, created from below, based in the real national agenda, not in the agenda the politicians and the media promote.”

The second line of questioning is whether the construction of Zapatista autonomy risks creating a state within another state. Marcos responds by saying: “The Councils of Good Government were born to attend to everyone: Zapatistas and non-Zapatistas, even anti-Zapatistas.” He goes on to affirm: “To respect is to recognize, and the Councils of Good Government recognize the existence and jurisdiction of the state government and the official municipalities, and in the majority of cases, the official municipal authorities and the state government recognize the existence and jurisdiction of the Councils of Good Government. In the same way that the Councils of Good Government recognize the existence and legitimacy of other organizations, they are giving respect and they in turn demand respect for their own forms of organizing.”

In contrast to past periods and in contrast to what he wrote about the Commissioner for Peace of the federal government, Luis H. Alvarez, Marcos recognizes, “Knowing that the intentions of Zapatismo are not just local, but also federal, the government of Chiapas chose not to be part of the problem but to try to be part of the solution.”

The third risk that the critics of autonomy pointed out was the possibility that conflicts would proliferate. Marcos explains that, on the contrary, conflicts have been diminishing and solutions have been sought that go beyond simple punishments. They also recognize jurisdictions such that state justice can be put into effect. He notes, however: “In the cases that have been presented thus far, the justice of the government of Chiapas has been remarkable in its lack of speed and inefficiency. It seems that the Chiapas judicial system is only expedient when it attempts to penalize the political enemies of the state government.”

The fourth “fallacy,” according to Marcos, refers to the administration of justice. He clarifies: “The good government does not seek to grant impunity to those who sympathize with it, nor is it designed to penalize those who have different ideas and approaches. The laws that govern the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Rebellion not only refrain from contradicting elements of justice that govern the federal and state justice system, but also, in many cases, complement them.”

He adds: “Collective rights (…) not only do not contradict individual rights, but rather allow that the latter reaches everyone, not just a few.” And he convincingly concludes this fourth communiqué by saying: “In Zapatista territory we are not planning the destruction of the Mexican nation. On the contrary, it is here that the possibility of its reconstruction is born.”

The fifth part presents a number of internal agreements including the conservation of forests and agreements against drug trafficking and the trafficking of undocumented immigrants. It is worth highlighting in this section, that, although it is not believed that electoral options constitute the path towards constructing democracy, the Zapatistas will not oppose the electoral day processes on October 3rd in Zapatista territories.

In the sixth part, Marcos introduces “six advances” assuring that living conditions in Zapatista communities, “even though still far from ideal, are better than in the communities that receive federal ‘support.'” These early advances have taken place in the areas of health, education, diet, land, housing, and the forms of self government.

… … … … … …

News Briefs

MONTES AZULES

At the beginning of July, twenty-five families from the community of San Francisco El Caracol were relocated to the new community of Santa Martha, in the municipality of Marques de Comillas. According to the official report, “of the 523 total hectares of Santa Marta, 13.46 were used for the construction of twenty-five homes and a common area with potable water services, electricity with solar cells, and latrine; a minimum number of streets and an access road were also constructed. Also the families were granted support for health and production projects and to guarantee services and development opportunities.”

With regards to the expensive and ostentatious project that the relocation had become, some analysts believe that the government was seeking to create a “model community” in Santa Martha in order to continue negotiating with the other communities that to date have not accepted relocation. In this sense, nothing has truly been solved.

Moreover, for the first time at the beginning of September, in reference to concrete cases in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, the Junta of Good Government of La Realidad condemned the threats of displacement received by the populations of Primero de Enero and Santa Cruz, which belong to the autonomous municipality of Libertad de los Pueblos Mayas. This declaration ratifies the Zapatistas position in the struggle for the land in the case of Montes Azules.

Impunity in Chenalhó

Two specific acts marked the escalation of tension in this Highlands municipality: in August, a Zapatista supporter was murdered in Polho (a case that is still unresolved). In September, the civil organization Las Abejas (“The Bees”) reported that children had found 190 bullets and subsequently declared “This is an example of how the injustice that we live everyday is shown. The paramilitaries, the real perpetrators in the Acteal massacre in 1997, are still armed and because of this we live in insecurity.”

Criticisms of the Justice System in Chiapas

Other cases have called attention to the failures of the justice system in Chiapas. An example of this is that, between January and April of the current year, four people were detained for the December murder of a teacher in San Cristobal de Las Casas. Reports indicate that three of the suspects had been tortured and that evidence had been falsified in order to find them guilty. In August, the defense lawyers of the accused and a witness were arrested for “attempted falsification of declarations” (a crime that doesn’t exist in the penal code). The Fray Bartolome de las Casas Center for Human Rights asserted, “We don’t know which interests are trying to unjustly find the detained guilty, but these actions are clearly an intimidation against the defense in order to hide the responsibility of the penal authorities for the crimes of torture and fabrication of evidence and maintain the accusation of homicide against the four that were arrested.” For more information, see also: www.laneta.apc.org/cdhbcasas/index.htm.

On the other hand, the President of the State Commission for Human Rights in Chiapas (CEDH), Pedro Raul Lopez Hernandez, was temporarily dismissed by the Chiapas State Congress (legislative power) on August 17th. The dismissal was on the grounds that the President of the CEDH had not permitted the work of the High Investigative Body (the body in charge of carrying out audits in cases of possible misuse of funds). The President of the CEDH denied the auditors entrance, arguing that they had failed to carry out established legal procedures for conducting audits on public institutions. It is feared that because of a lack of a clean and transparent audit of the CEDH (and the possibility of impeding the autonomous work of the CEDH through the auditing process), the CEDH’s ability to report on human rights violations will be affected. (see also in Frayba website)

FOLLOW UP ON THE CASE OF GUADALAJARA

In their July report, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) reported that police authorities in Jalisco subjected demonstrators to illegal detentions, cruel and degrading treatment, and physical and psychological torture on May 28 during the third Summit of Latin America, the Caribbean and the European Union in Guadalajara.

The CNDH recommended that the governor of Jalisco, Francisco Ramizez Acuna (of the PAN party), circulate the necessary instructions to start the administrative process that would hold the implicated public servants responsible. The governor has continued to insist that the report “is partial” and that “we have a clear conscience for the actions that we took against those who came to attack Guadalajara and Jalisco.” In spite of growing pressure from national and international human rights organizations, seventeen young people remain in jail in Guadalajara and forty-nine are out on bail but continue to be processed.