2017

22/01/2018

IN FOCUS: Indigenous Peoples – “Great challenges and obstacles for the effective enjoyment of their rights”

02/04/2018In November, the General Law on Enforced Disappearances and Disappearances by Individuals was promulgated. The Movement for Our Disappeared affirmed that, “it is a sign of goodwill in the face of the magnitude of the disappearance crisis.” However, it demanded that, “the promulgation has a clear route for implementation and has adequate and sufficient resources.” It should be remembered that Mexico has more than 32,000 people missing and that a survey conducted by the Chamber of Deputies showed that most Mexicans classify the searches conducted for missing people as bad, and as bad or very bad efforts to punish the culprits. In January, when the law entered into force, the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances of the United Nations warned that, “if progress is not made in the fight against impunity, it will be impossible to stop this scourge.”

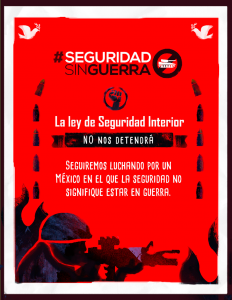

“The Law of Internal Security would bring Mexico closer to being a militarized state”“, poster of # Méxicosinguerra

Other bills or laws approved in recent months are worrying from the human rights perspective. The most controversial has been the Internal Security Law that aims to regulate the actions of the armed forces in public security work. Among other aspects, it establishes the procedure by which the president may order the intervention of the armed forces when “threats to internal security” are identified and when police capabilities are insufficient to deal with them.

It has been strongly questioned by national and international civil organizations, as well as by opposition parties that believe that it would militarize the country even more and that it would open the door to more human rights violations. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, acknowledged “that Mexico faces a huge security problem (…). More than a decade after the armed forces were deployed in the so-called war on drugs, violence has not diminished and both state and non-state agents continue to perpetrate abuses and violations of human rights.” For this reason, he considered that “regulating the operations of the armed forces in the work of citizen security is not the appropriate response. The current legislative project could weaken the incentives that civil authorities have to fully assume their functions.”

However, in December, President Enrique Peña Nieto promulgated the law although he affirmed that he will not implement it until the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN in its Spanish acronym) rules on its constitutionality. By February, more than ten challenges had been filed before the SCJN, including actions promoted by deputies, senators, the National Commission for Human Rights (CNDH in its Spanish acronym), the National Institute of Transparency, Access to Information and Protection of Personal Data (INAI in its Spanish acronym), as well as by the municipalities of several states.

Similarly, the Biodiversity Law was approved by the House of Senators, which, according to civil and academic organizations, puts Mexico’s natural resources at risk. They denounced the omission of the prohibition to carry out mining activities and the generation of electric power in Protected Natural Areas (PNA). Greenpeace Mexico also criticized “the scarce protection of genetic resources and their commercialization, which could exacerbate conflicts associated with access and distribution of benefits to local communities or indigenous peoples.”

In February, the General Water Law began to be discussed, which would move towards greater privatization and variations in costs depending on the utility that the operator should achieve; as well as a new labor legislation that could generate even more precariousness.

“They were taken alive, we want them alive”, a protest against forced disappearance © SIPAZ, archive

Human rights: generalized crisis

At the beginning of 2018, Human Rights Watch published its report on the situation of human rights in the world. In the case of Mexico, it highlighted the abuses of members of the armed forces, impunity in emblematic cases (such as Tlatlaya and Ayotzinapa), the habitual use of torture, the Law of Internal Security and violence against defenders and journalists, among other points.

After an official visit, the United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Freedom of Expression and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights stressed that “violence against journalists has been a crisis for Mexico for more than a decade and despite the creation of mechanisms of protection and persecution on the part of the Government, the impunity and the insecurity continue to characterize this situation.”

Regarding migrant rights, in December, the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement (MMM) reported that, “approximately 500,000 people cross the southern Mexican border each year. (…) Economic insecurity combined with the impact of mega-projects for the extraction of minerals and other resources create a situation of structural violence and forced displacement. This economic precariousness occurs in a context of acute violence in these countries that have the highest levels of homicide and gender violence worldwide. When migrants flee these conditions, they encounter serious threats during their journey through Mexico, where the violence of criminal groups and the corruption of state institutions results in migrants being kidnapped, extorted and trafficked by organized crime groups.” The MMM also stated that “the Mexican government, in cooperation with the government of the United States, has tried to prevent the migratory flow from reaching the northern border through the militarization of the territory,” which has increased “the vulnerability of the migrants in transit. “

2018 Elections: promise to be harder fought and more expensive than ever

According to a Pew Research Center study conducted in 38 countries, Mexico is the least satisfied country with its democracy with only 6% of Mexicans satisfied with its functioning. In this context, next July 1st, a new president of the Republic, 128 senators and 500 federal deputies will be elected. In addition, some states will elect state and local representatives such as governor, mayors and other officials.

Regarding the presidency, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador at the head of the National Regeneration Movement (Morena) will try for the third time to win the elections. Until February, the polls placed him in first place in voting intentions. Jose Antonio Meade Kuribreña, who was secretary of the Treasury, Social Development and Foreign Affairs, will be the candidate of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). PAN’s Ricardo Anaya is to be the candidate of the Por Mexico al Frente coalition, an atypical alliance between the conservative National Action Party (PAN), the Social Democratic Democratic Revolution Party (PRD in its Spanish acronym) and the Movimiento Ciudadano (Citizens’ Movement).

Of the 53 independent candidates, only three met the requirements of one million valid signatures that reflect territorial dispersion: Margarita Zavala, wife and former PAN President Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), Jaime Rodriguez Calderon (known as ‘Bronco’, current governor of Nuevo Leon) and Armando Rios Piter (currently senator for the PRD). Maria de Jesus Patricio Martinez, Marichuy, the candidate nominated by the National Indigenous Congress (CNI in its Spanish acronym), managed to collect 275 thousand signatures in her unsuccessful attempt to register. From the beginning, Marichuy and the CNI made it clear that they did not want to gain power, but to promote issues such as indigenous peoples’ rights and women’s political participation, as well as organizing and consolidating an Indigenous Council of Government (CIG in its Spanish acronym) at the national level.

Chiapas: Growing Insecurity and Conflict

Two violent deaths in January alarmed society in the face of growing insecurity in the state: that of the biologist and professor at the University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas (Unicach), Adan Gomez Gonzalez and the femicide shortly before of Gloria Castellanos Balcazar, 24 years old, also in Tuxtla Gutierrez. An article on the Chiapas Paralelo website emphasized that “when we identify with these facts, we recognize the others that have remained hidden, those of anonymous but no less painful deaths, of the three people who die in Chiapas violently every two days.” The Citizen Security Observatory and ChiapasLigaLab has also documented the increase in cases of extortion, vehicle theft, kidnapping, burglary and rape.

With the feminicide of Gloria, Voces Feministas [Feminist Voices] collective affirmed that “gender alerts, preventive and procurement systems do not work in Chiapas, because public policies in this regard are reduced to announcements and declarations.” Since November, and one year after the Declaration of Gender Violence Alert in Chiapas, the Popular Campaign against Violence against Women and Femicide denounced government actions and omissions. It also claimed that the budget for the Alert is a “political booty of corrupt officials who steal the money from the people, as happens with the resources for those affected by the earthquake of September 7th.”

Chiapas Highlands: Main Flashpoint

“Stop violence and corruption. Solve the problem now” Chenalhó Chalchihuitán”, banner in the pilgrimage of Pueblo Creyente, January 2018 © SIPAZ

The main flashpoint in the last three months has been the Chiapas Highlands. An agrarian conflict dating from 1973 over limits between the municipalities of Chalchihuitan and Chenalho was reactivated with unprecedented violence in November. Gunshots, houses burned, and groups of hooded civilians carrying high-powered weapons spread terror in the area, causing the displacement of more than 5,000 people. Particularly striking, as the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas emphasized, was “the impunity with which the armed groups act to the extent that neither the police nor the Army have been able to make themselves present to prevent violence, nor to disarm those who impose their control over the territory and the population through fear.”

On December 13th, the Unitary Agrarian Court finally ordered the return of 365 hectares of land to the municipality of Chenalho by that of Chalchihuitan. It was ruled that compensation will be paid to those who will lose their lands and homes in Chalchihuitan. It should be noted that the Court’s decision is dated November 6th, more than a month ago, during which time, as reported by the Diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas “the displaced population has suffered fear, cold, hunger, harassment, illness, psychological damage and even the death of several infants and adults.”

In January, nearly 4,000 indigenous people from Chalchihuitan returned to their communities after almost two months of forced displacement, despite not having the security conditions to do so due to the presence of groups that have not been disarmed. 1,165 people refused to return for that same reason. Those who returned did so because of the conditions of forced displacement that caused the death of 11 people due to hunger and cold, the parish priest of Chalchuitan said.

Post-election or pre-election conflicts?

On the one hand, post-election conflicts of the 2015 municipal elections have not been solved: in the worst scenarios, in January, heavily armed civilians attacked residents who have been demanding recognition of their right to self-determination and the formation of a community government in Oxchuc. The toll was three dead and 17 injured. The elected mayoress, Maria Gloria Sanchez, had been expelled from the municipality by residents who rejected her and her husband who alternated power for three terms of office, first by the PRI, and, in this last term, by the Green Ecologist Party. In February, the State Congress dismissed her to initiate an investigation against her.

On the other hand, new conflicts appear to be happening within the electoral context of July 1st, when in Chiapas, in addition to the federal elections, elections for governor and municipal elections will be held. The process of defining candidacies and in particular those that come from alliances between parties has been particularly rarefied and of multiple changes up to the time of writing, particularly because the alliance between the Green Party, PRI and Nueva Alianza that was defined at the federal level generated conflicts and ruptures at local level since the Greens accused the PRI of wanting to impose its candidate. It should be remembered that a large part of the postelectoral conflicts of 2015 resulted precisely from tensions between the PRI and Greens in Chiapas. The PAN, PRD, Movimiento Ciudadano and Moviendo Chiapas and Chiapas Unidos parties will register a common candidacy, where the candidate could be Eduardo Ramirez, who resigned from the Greens in January and is former government secretary of the current governor. The other candidates would be Roberto Albores Gleason, representing the PRI, Greens y Nueva Alianza, and Rutilio Escandon, candidate for Morena, PT and Encuentro Social.

Defense of human rights between complaints and construction of alternatives

Mass celebrated in the context of the pilgrimage of Pueblo Creyente of the diocese of San Cristobal de Las Casas, Chiapas, January 2018 © SIPAZ

On November 2-, the Movement in Defense of Life and Territory (Modevite in its Spanish acronym) was mobilized 107 years after the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. It stressed that “the marginalization and misery of our peoples persist; violence is the daily bread and insecurity is what is breathed in the environment. Coupled with this, the colorful circus of political parties divides us, and they take advantage of our poverty” while governments at all levels “are accomplices of dispossession, abuses, violence and injustice.” It requested a positive response to the requests submitted by the Community Government Commissions of the municipalities of Chilon and Sitala so that they can be governed according to their own indigenous normative system.

In January, indigenous people from Amador Hernandez, municipality of Ocosingo, expelled 17 members of the Navy from their community that entered their territories without their permission. The community and other organizations denounced that, “it was a surveillance operation and control of our communities in the framework of the implementation of the Environmental Gendarmerie announced in 2016. It is a new body of the Federal Police officially charged with “guaranteeing and safeguarding natural protected areas” and informally control and repress the population to preserve the interests of government and business.”

The community of Amador Hernandez expels soldiers from its territory, January 2018 © habitantes de Amador Hernández

On January 2-, Believing People organized a pilgrimage of more than 5,000 people. It reaffirmed that they continue with “the firm task of the struggle for freedom, peace with justice and dignity for the benefit of the peoples.” It rejected the “dispossession of the Land and the Territory and the privatization of natural assets”, the impulse of structural social reforms, corruption and impunity and the fact that “throughout the country, and particularly in Chiapas, adequate consultations are not carried out when laws are drafted or projects are developed that affect the territories and rights of indigenous peoples”, among other points.

Also in January, workers in the health sector denounced the repression and criminalization they are suffering. They explained that despite being the state with most support for health in the federal budget, Chiapas has a shortage of medicines and poor infrastructure due to the situation of corruption and mismanagement. They denounced the arrest warrants for rioting issued against four workers who had participated in the hunger strikes in 2017. Limbano Dominguez Alegria was arrested for the same reason.

The theme of Land and Territory remains omnipresent: in February, organizations from Canada and Mexico, relatives and friends of the environmental defender Mariano Abarca Roblero, killed in 2009 in Chicomuselo, asked the government of Canada to investigate diplomats from the Embassy of that country that. They accuse the Embassy to have covered up the actions of the mining company Blackfire Exploration that was linked to that crime that remains unpunished.

Oaxaca: perception of growing insecurity

In November, the governor of Oaxaca, Alejandro Murat Hinojosa of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI in its Spanish acronym) delivered his First Government Report. While acknowledging that much remains to be done, he affirmed that, “the bases for the development of the state have been established.” The political parties of the opposition pointed out the lack of attention to the needs of Oaxacans. The magazine Sin Embargo highlighted that the delivery of this report occurred “in a climate of complaints, insecurity and distrust.” While the governor said that “in Oaxaca nothing happens, we can leave our homes quietly, using public transport”, Sin Embargo said that “the statistics say the opposite: robberies with violence in Oaxaca total (from January to September) 2,722 (…). In the same period, 703 malicious homicides were reported.” Furthermore, the act took place in the midst of a mobilization of Section 22 of the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE in its Spanish acronym) which stated that one year into Murat’s government “the account is pending, in the absence of answers in the educational, social, legal, humanitarian and political field for the people of Oaxaca because it has only received palliatives and the administration of demands.”

The increase in insecurity is even greater for defenders and journalists. In January, the Consortium for Parliamentary Dialogue and Equity organization denounced a series of attacks against it. They stressed that since 2011 they have suffered 11 breaking and entering. They stressed that “of the three complaints that have been filed during this six year period, there has been no result whatsoever (…), which undoubtedly has given the message of consent and complicity of this Government.” The National Network of Women Human Rights Defenders documented that in Oaxaca there are 58% of aggressions against women defenders nationwide.

Another example was that in January, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) ordered Mexico to protect the life and integrity of Bettina Cruz in the face of the risk she faces for her work defending the rights of indigenous peoples who oppose the construction of wind projects in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Shortly before, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation took on the case of the Eolica del Sur project in which the absence of consultation has been reported. Bettina Cruz declared that “every time we present a national or international recourse, our lives and those of our communities are in danger. Every time we win, the risk increases. (But …) despite having clear decisions at different times about the social and environmental risks of the project and the violation of the right to consult our communities, the government and companies continue to develop it without shame.”

Among other examples that affect not only defenders but also journalists, in January, the reporter of Sol del Istmo, Agustin Silva Vasquez, was reported missing (the Human Rights Ombudsman of the Peoples of Oaxaca documented 144 attacks against people exercising their right to free expression in 2017); and, in February, three members of the Committee for the Defense of Indigenous Peoples (CODEDI in its Spanish acronym) lost their lives and two were injured during an armed attack after holding a meeting with authorities.

Guerrero: Daily Violence

Attack on the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities-Community Police (CRAC-PC) of La Concepcion, Guerrero © Tlachinollan

Violence continues to be the order of the day in Guerrero. Alarmingly, in 2017, 149 femicides were committed in the state. The Tlachinollan Human Rights Center denounced that, “the brutality with which women are murdered has increased exponentially. They are realities that horrify along with the perpetrators.”

In January, European parliamentarians expressed their concern over the situation of Mexican human rights defenders, and in particular, in the case of Guerrero, “the relatives of disappeared persons, the communities that have been forcibly displaced, as well as the people and human rights organizations that accompany them.” Soon after, members of the Regional Coordinator of Community Authorities – Community Police (CRAC-PC in its Spanish acronym) from La Concepcion, municipality of Acapulco, were ambushed by armed persons. Hours later, the state government mounted a police-military operation of more than 100 elements who searched the houses of the members of the Council of Ejidos and Communities Opposed to the La Parota Dam (CECOP), without legal order. 11 people died in these events, 38 were arrested, ten of which reported torture.

Since November, workers from the mining company Media Luna, of the Canadian company Torex Gold Resources, have launched a strike to “demand the change of ownership of their collective bargaining agreement.” Several newspapers reported that the problem resulted in the murder of three employees. In January, police and soldiers took control of the mining facilities and broke the strike. The Mexican Network of those Affected by Mining (REMA in its Spanish acronym) noted that “this problem has a framework, and it is the current federal and state policy of delivery of resources and unrestricted and servile support to domestic and foreign companies that impose this type of exploitation, affecting territories irreversibly in environmental, social and health terms.”

Journalists are another vulnerable sector. El Sur reporter, Zacarias Cervantes, denounced that in November he was intercepted by about seven men who searched his car and took his cell phone. In February, journalist and blogger Leslie Ann Pamela Montenegro del Real, aka “Nana Pelucas”, was murdered in Acapulco. Since December 2016, she had been threatened by drug dealers. Tlachinollan repudiated that the prosecutor’s investigation focused its efforts against the victim seeking to link her with organized crime.